Point to Paper – Armie Hammer’s Great-Grandfather and the Mystery of the Pencils from Oslo

Did you know that Norway once had five pencil factories? My colleague Anders wrote a very good article about this in January (link to the article). Their history is unknown for most people even in Norway. Did you know that Norway’s pencil history probably started as early as in 1768? That is remarkably early if you also know that the first wooden pencil in the US was made in 1812. On the website Pencils.com it is stated: “Early settlers depended on pencils from overseas until the war with England cut off imports. William Monroe, a Concord, Massachusetts cabinet-maker, is credited with making America’s first wood pencils in 1812. Another Concord native, famous author Henry David Thoreau, was also renowned for his pencil-making prowess.”

The first Norwegian pencil company had an impressive name. It was called the Englisdahlske Blyants- og Isenfarve-Værk (Englisdahlske Pencil- and Graphite-works). If you are visiting Norway, remnants can still be found at Bjørnåsvannet in East-Agder in the south of Norway. The company was situated in Blyantverksveien (Pencilworks Road). The road still exists. You can still find graphite in the area.

The people that work with this Blog, Anders Kristiansen, Liv Mogstad Strickert and I, do a lot of research on handwriting, ink and handwriting tools. One thing we have noticed is that the history of old companies is mostly quickly forgotten. This also means that the connections between them are even more difficult to bring to light. We have found several links between North-American made and Norwegian made pencils, but the stories behind the connections have been hard to untangle. It is a work in progress and we constantly find new clues through our investigations. We are thankful for input if any of our readers have information. An example can be seen in the picture below. The Templar 777 pencils from Reliance Pencil Company from New York are remarkably similar to the Monark pencils from Oslo Blyantfabrikk (Oslo Pencil Company). There clearly is a connection, but we just don’t know what it is (yet).

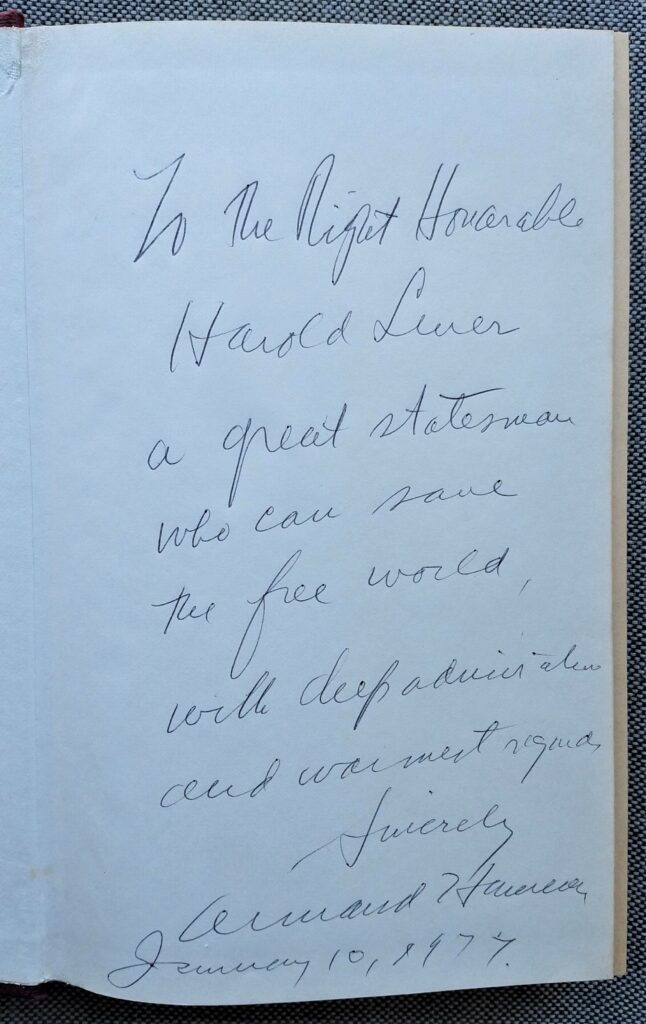

Another such story that has evaded us is the potential link between Den Norske Blyantfabrikk (The Norwegian Pencil Company) that was located in Oslo (Norway) and the A. Hammer Pencil Company that once existed in Moscow (Russia). What has this to do with American pencils you ask? Well, Mr. Armand Hammer was an American and he was known as Lenin’s favorit capitalist. In this article I will concentrate on telling his story. I will speculate more about the possible connection between his company and the Norwegian company towards the end.

In this edition of Point to Paper, you will get to know a rare pencil and a clever capitalist. Important sources for this article have been Henry Petroski’s book from 1989, The Pencil, and Bob Considine’s book from 1976, Larger Than Life – A Biography of the Remarkable Dr. Armand Hammer. You will also find several links (blue letters) throughout the article.

The story you wil be presented is more like a fairy tale than a story from real life. How it all actually happened varies a little depending on which sources you use, but essentially everything you are about to read is true. Today’s post is also about being able to identify elementary needs in a communist country and finding out how to make money under these conditions. Some people see opportunities everywhere. Do you know who contributed to the development and production of quality pencils in Russia? He was American and his name was Armand Hammer. You have probably seen a movie with his great-grandson. The great-grandson is Armie Hammer. He is known, among other things, as an actor in the the fairytale movie Mirror Mirror with co-star Julia Roberts and the action comedy The Man from U.N.C.L.E.

Armand Hammer came to Russia in the summer of 1921. He came with a plan to make money. He wanted to do business in a virgin market and arrange deals to import medicines and chemicals from the family business in the US. There are many opinions about Dr. Armand Hammer. Some portray him as a selfish and crude businessman who was mostly concerned with creating a lavish legacy for himself. Others, not least himself, regarded Hammer as a skilled businessman who was good at spotting opportunities, good at charming future business partners and an expert at landing the best deals. There are many indications that he was a bit of all of these elements.

An example of his need to create a great legacy can be when he in 1990 he opened a museum named after himself. It’s not really that special. Rich people do things like that all over the world. We have several similar examples of rich people doing the same also in Norway. His most famous and exclusive purchase was the Codex Leicester. It is one of the most famous objects in existence. It was made by Leonardo da Vinci. It is a 72-page book with scientific reflections and drawings made by da Vinci himself. Hammer tried in vain to change the name of the book to Codex Hammer. That might also sound like a wild and eccentric idea, but the idea is no stranger than that one of the book’s former owners, the Earl of Leicester, Thomas Coke, chose in 1719 to do just that. Hammer could actually claim that he was trying to follow a tradition. The book is still called the Codex Leicester. Bill Gates is the current owner.

The year Hammer came to Russia, Lenin had been in power for almost four years. The country was changing and under construction. There was a need for almost everything. There were endless possibilities for those who managed to find out how society worked. Hammer was creative and good at maneuvering in new and unfamiliar situations. The Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic was born on 7 November 1917, but in Hammer’s own memoirs the country was still referred to as Russia. The Soviet Union was officially established in 1922.

Hammer came to a country characterized by hunger and depression. On the other hand it was a country with an abundance of resources. Hammer believed that the Russians lacked initiative. He claimed that Lenin was worried about the same thing. Hammer himself was full of courage and energy. He immediately set about importing grain from the United States. He was businessman enough to understand that the boats shipping grain could not return empty. He filled the returning boats with valuable Russian goods like furs and Russian caviar.

Lenin got wind of the fact that there was an enterprising American operating in Petrograd. He arranged it so that they could meet. Lenin and Hammer traveled together and talked together. Hammer spoke Russian flawlessly and elegantly. He willingly shared his thoughts on what he thought he could manage to import and what he could achieve. Hammer himself claims that Lenin was disillusioned by the development and missed someone taking action. Lenin also needed people who could procure necessary goods. Hammer was ready for any and all opportunities. Lenin sorted out the bureaucracy. In record time, Hammer received very special privileges and could trade almost without restrictions. He also established fur trapping stations throughout Russia and began mining for the sought-after raw material asbestos. It all turned into a thriving business.

Not surprisingly for Armand Hammer, after a few years he was told that the Soviets wanted to take control of imports and exports themselves. Hammer had made good money, but didn’t feel quite done with the country yet. The next opportunity came as a proposal from Leonid Krasin . He was also the one who had brought the bad news. Krasin had a new proposal. Maybe Hammer could start industrial production instead? Hammer was as always positive, but he wondered what he should start producing. The answer came by chance one day when he was buying a pencil.

At that time, a pencil cost between two and three cents in the United States. The store he happened to drop by in Moscow sold everything in office supplies. In this store, a single pencil cost 26 cents (50 kopecks). He could only buy it if he also bought stationery. The price was not unusual for Moscow. Pencils were mainly imported from Faber in Germany. At the time, Faber was among the leaders in the world in technology for the mass production of pencils. Their pencils were expensive and there were few stores that sold them. The stationary dealer was willing to sell just a single pencil to Hammer since he was a foreigner, but then he would have to pay 52 cents (1 Ruble). In the US you could get over two dozen quality pencils for the same price.

Hammer could not have received better inspiration. In October 1925 he entered into an agreement with the authorities. Not only did he promise that he would have a factory up and running within twelve months, but by that time he also promised to have produced pencils to a value of at least one million dollars. There was just one catch. Hammer knew nothing about making pencils. In an article about one of the factories established in Moscow in 1926, interestingly named after Leonid Krasin, it is described how a pencil requires 83 technical operations, a production time of 11 days and 107 different raw materials. As recently as 1990, pencils were actually rated among the top 700 most complex articles in production. Hammer had no idea what he had gotten himself into.

Hammer was not afraid of a challenge, but he had no intention of inventing the solution all by himself. He took a shortcut and traveled directly to the place where most of the pencils in the Soviet Union came from. The pencils that were sold in Moscow and the rest of the country were mainly produced in Nuremberg. What met Hammer there was secrecy and factories that were protected like fortresses. It was no easy matter to attempt industrial espionage in Nuremberg’s pencil industry. Hammer was not intimidated and did not lack imagination.

Hammer picked up on a rumor that there was a disgruntled employee in town. He managed to find a vengeful pencil engineer that felt badly treated. It was perfect for Hammer. The engineer was easy to convince. Hammer offered him four times his current salary if he was willing to change employer. Together they even managed to buy new German machines specially made for producing pencils. They made it look like they were representing a German company that was going to build a new pencil factory in Berlin. Others had tried to buy German machines for export in the past without success. Hammer had the machines delivered to Berlin and secretly sent them on to Moscow by train. Hammer also recruited all the dissatisfied pencil workers he could find. He managed to smuggle the German workers out of the country by making it look like they were going on a group holiday to Finland. There he had prepared transport and a work visas for them onward to the Soviet Union.

This whole achievement is actually remarkable. Any person with real knowledge of the complexities of making pencils would have said that starting a pencil factory from scratch, and making money within one year, would be impossible. Hammer’s ability to solve the problem was amazing. He had tapped into decades of research and development, had aquired all the manpower and machines needed and he had in this way made the impossible possible.

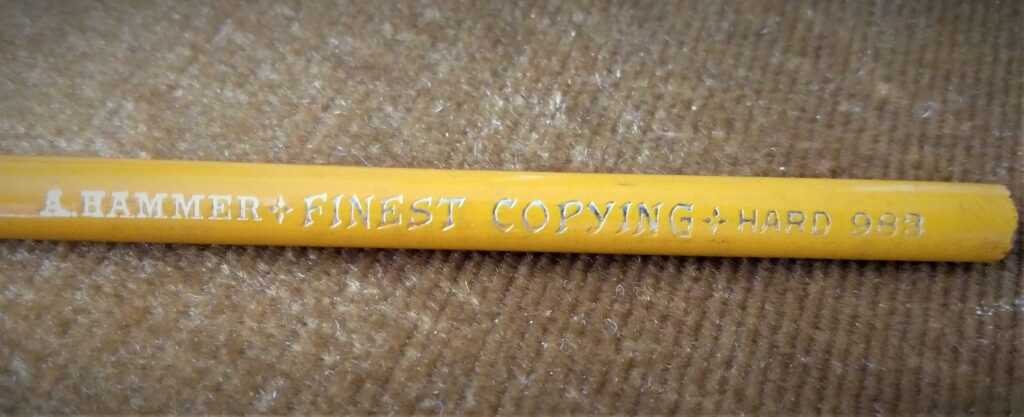

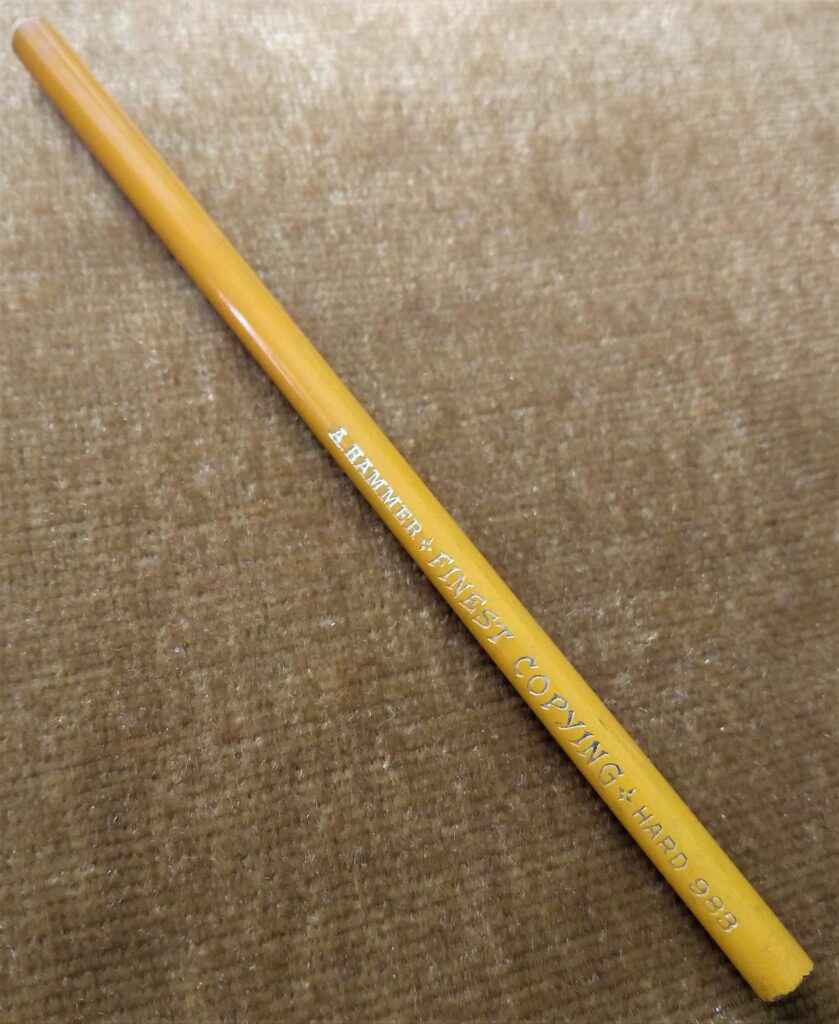

At record speed, a factory was set up on the premises of an old soap factory in Moscow. Six months ahead of schedule (!), he was able to fulfill all the promises he had made to the authorities. Only four years after the agreement was made, towards the end of 1929, Hammer had managed to establish five pencil factories. Already in the third year, Hammer produced over seventy million pencils annually. It was actually more than the market in the Soviet Union could absorb. For a while he could export twenty percent of the production. The most popular pencils were called Diamond. They were packed in boxes marked A. HAMMER – AMERICAN INDUSTRIAL CONCESSION, USSR

There is a fascinating and more hidden layer of this story. The factories were also a kind of free haven for those persecuted from the old regime. The wages were very good. Many of the employees were professors, writers, generals, captains, former political leaders and even former noble ladies. Everyone living in the Soviet Union at the time was trying to create a new identity as legitimate workers. With the best wages, the pencil factory became a popular workplace and an ideal place to bring about a personal transformation to becoming a working man acceptable to the Soviet state.

As always, Hammer was aware that this golden age could not last forever either. He was well pleased when the Soviets chose to buy the factories in 1930. One of the factories was renamed the Sacco and Vanzetti Pencil Factory. I haven’t been able to find any direct documentation to support my claim so far, but I think another of the five factories was the one that later got the name Krasin. The Krasin pencil brand still exists and the factory is said to have been established in 1926. Leonid Krasin was the one who suggested that Hammer should begin industrial production. There many interesting coincidences that suggest that the Krasin factory was one of the factories started by Hammer.

The names Sacco and Vanzetti were not chosen randomly. Sacco and Vanzetti were two Italian anarchists living in the United States. In 1921, they were both innocently sentenced to death. They were executed in 1927. The sentence was overturned only in 1977. In 1921, 250,000 people demonstrated in Boston in a silent protest against the sentence. In Stockholm, 50,000 demonstrated. Albert Einstein and George Bernard Shaw were among those who protested publicly. In the Soviet Union, tragedy became propaganda. Sacco and Vanzetti became communist martyrs. They were honored by having a pencil factory named after them. No capitalist could have marketed the pencils better.

The Norwegian Pencil Company was started in 1932. Anders Kristiansen writes in this blog: “The brothers Jens Hagerup Nikolaisen Vassvik and Aksel Emil Vassvik were born respectively on September 22, 1884 and May 29, 1893 on Tranøy, on the south tip of Senja, a big island in the far north of Norway. Their parents’ names were Nicolai and Ingeborg Jensen, and the two brothers were part of a group of nine or ten siblings. Some of the siblings (unclear how many, although one source suggests two brothers and two sisters) emigrated to America around the turn of the century.” There is a North-American connection here, but it is not likely that it has anything to do with pencils. Still, an American businessman making pencils i Moscow that were exported, and that you also could buy in Oslo, might have caught the attention of the brothers or at least inspired them.

There is more though. The Norwegian Pencil Company was founded on March the 3rd in 1932. That meant that only between one and two years after Armand Hammer had sold his business in Moscow, a pencil company was started in Norway. Not only did they start making pencils, but as you can see from the picture above, they made pencils of the same shape, color and type. A. Hammer Pencil Company had the round and yellow Diamond pencil and The Norwegian Pencil Company had the nearly identical round and yellow Diamant (Diamond in Norwegian).

One even bigger unanswered question is were the brothers got hold of the technology and know-how needed to make pencils. They would surely have encountered the same problems that Armand Hammer did. They did not have the same resources as Hammer. I suggest a possible link. There were many high profile Norwegians from Oslo in Moscow in the 1920s and 1930s. The likelihood of them meeting Hammer as a fellow foreigner in Moscow would have been relatively high. It is therefor more than possible that the story about Hammer and his pencil factories reached Norway. A scenario where some of the workers from Moscow needed to flee and establish theselves in Norway is also possible. Hammer’s know-how had value and someone connected to him or his factories would have wanted to preserve it. We will share more when we find new clues to this mystery.

References

Henry Petroski (1989). The Pencil. London: faber and faber.

Bob Considine (1976). Larger Than Life – A Biography of the Remarkable Dr. Armand Hammer. London: WH Allen.

Other sources can be found if you press the blue letters in the text. They are links to additional material and references.

Photos

All photos were taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy. No pencils were sharpened during the work on this article.