Point to Paper – Grandma’s handwritten cookbook and her famous Norwegian meatballs

Old handwritten cookbooks can be wonderful treasures. Of course they have recipes, but they also carry history. They often give insight in to the family that used them and the era in which they were written. Cookbooks are tools. They are not intended to be decorative items. They tend to be rough around the edges. If they are not, they are either new or were never very interesting in the first place. Cookbooks can be written with a fountain pen, a pencil, a marker or a ballpoint pen. They are often full of corrections and adjustments. Buying a new stove can result in temperatures having to be changed to make the good old bread recipe work as before. Stains from grease and tomato sauce are part of the charm. It is easy to recognize a beloved cookbook. It is usually well worn and repaired multiple times. Are you looking for the best recipes? Here is a hot tip: Look for the pages with the most stains.

There are many varieties of cookbooks. In this post, I will share some golden moments from some of the ones I love. At the same time, I want to follow up on a thought from a previous post. Writing a cookbook by hand can be a way to be remembered. It can be a way to leave a legacy behind that can be enjoyed long after you are gone. Remember to add dates, comments and current events. That will give the cookbook even greater personality and historical value.

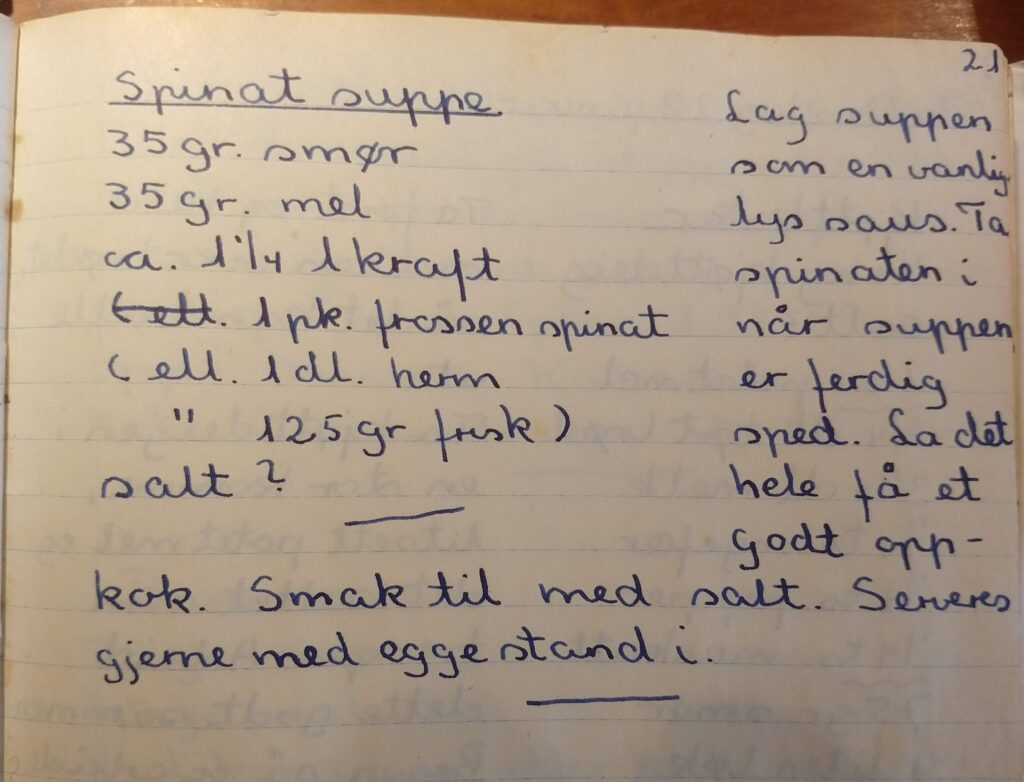

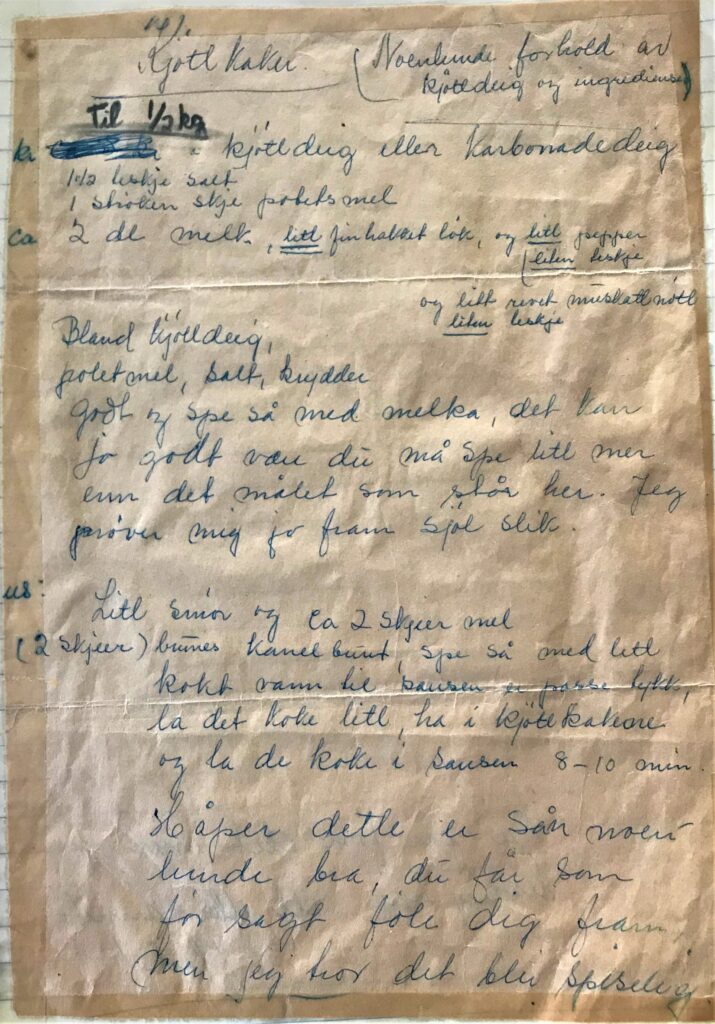

In a letter that is pasted into my mother’s old cookbook, it reads: “Buy approximately Kr.8,- worth (approximatly $1) of minced meat.” That one sentence is a whole story in itself. My mother had recently married my father and was pregnant with me. She had not been allowed in the kitchen growing up. Grandma Aslaug, my mother’s mother and my grandmother, had grown up on a farm. The family had a reputation for making excellent food. She had also been a professional cook before she got married in 1937. She liked to run her kitchen in peace and alone. She needed to do things her own way. In practice, that meant everyone else had to stay away. When her daughters, my mother Liv and my aunt Berit, got married, they were therefore lacking some essential kitchen skills.

Grandma Aslaug had to make up for her two daughters’ lack of housewife training. Remember this was the 1960s and it was before the feminist movement had reached most homes in Norway. Moms ran the house and dads went to work outside the home. My grandmother could in some sense be accused of not having done a proper job of educating her daughters. I am sorry, I know this sounds terrible in 2024. Grandma tried to make up for this by sending a steady stream of letters to her daughters. As a young boy, many years later, I was strangely enough very welcome in to my grandma’s kitchen. Grandma loved her grandchildren. We were all boys. We were her sweet boys. Making many dinners with grandma might have been the reason that both of my brothers and myself all ended up becoming restaurant chefs.

In the 1960s, my grandmother and my grandfather lived in the officers house at Sverresborg fortress in Bergen. Grandpa was an army engineer and was the officer in charge of buildings and structures at the fortress. The house was a beautiful building from the 18th century with a nice garden and a marvelous view of city. I was lucky enough to live there with grandma and grandpa from 1968 to 1969.

Grandma Aslaug’s famous meatballs

1/2 kilo (1 pound) minced meat

1 egg

1 1/2 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon potato flour

2 deciliters (0.8 cup) of whole milk (3.5-4.5 % fat)

1/2-1 small finely chopped yellow onion

1/2 teaspoon black ground pepper

1/2 teaspoon ground nutmeg

Mix it all with your hands to a smooth dough. That will make the meatballs less tough than in a mixer. Make the meatballs “golfball” size, flatten them slightly and fry them on each side in real butter. Make the sauce from 60 gram (2 oz) real butter and 60 gram (2 oz) wheat flour and make a brown roux by cooking it slowly until it gets a cinnamon color. Add 8-10 deciliter (4 cups) water, a stock cube and the meatballs. Lett it all simmer lightly for 20-30 minutes. Serve with potatoes, lingonberry jam and vegetables. Many Norwegians prefer cabbage stew in white sauce with their meatballs (me included):

Grandma’s Norwegian cabbage stew

75 grams (2.5 oz) of real butter

75 grams (2.5 oz) of wheat flour – melt the butter, add the flour and mix

1 1/2 liters (6 cups) of whole milk – add all in one go (white Norwegian sauce – the same as for fishballs)

1/2 teaspoon nutmeg and mix/whisk all the time and bring to boiling.

Salt to taste – some (me) also use a little bit of black pepper.

1 1/2 kilo (3 pounds) finely sliced and ready boiled cabbage (weight about 1 1/2 kilo (3 pounds) before boiling) – some people like carrots (8-12 boiled carrots) also in slices. It makes the cabbage stey to a carrot and cabbage stew – slightly sweeter. I like both

Grandma’s letters contained both recipes and encouragement. For example, she wrote: “Practice makes perfect!” – “Don’t buy meat with yellow fat – then it’s an old animal.” – “Remember to taste along the way.” The recipe, asking for $1 worth of minced meat, was part of a letter that my grandmother wrote in 1967. It states that minced meat for $1 would be enough for making four portions of meatballs. Just think about the history this one recipe carries with it. It tells us about forms of communication. Mom and grandma communicated through handwritten letters. My mother didn’t have a phone. She had to go to the central telephone exchange, in the center of the village of Lyngen, if she wanted to make a call. That was expensive, so it was only for special occasions. The letter also tells us about being newly married and inexperienced with housekeeping. It tells us about the cost of food in 1967. That year, you got 1/2kg (1 pound) of minced meat for $1. Above is a translation of the recipe for Grandma Aslaug’s famous real Norwegian meatballs (4 portions):

Another grandmother, grandma Inger, was also proud of her cooking. Grandma Inger was not my grandmother, but my mother-in-law. Grandma Inger went to Bergen Kommunale Husmorskole (Bergen Home Economics School) in 1958. It was located in Monclearhuset (House of Monclear) at Møhlenprisbakken number 12 (street address in Bergen) from 1914 to 1977. For many young women, this was a good way to build up skills for their role in a future marriage. Inger was also educated as a pediatric nurse and worked as an assistant nurse most her adult life.

As a married woman, she managed the household. Grandpa Terje (her husband) had a busy job as an engineer. In most families, the economy depended both on someone earning money and on someone managing the money with moderation and prudence. Inger was both moderate and smart. I have to add that it wasn’t the case that grandpa Terje didn’t do anything at home, far from it, but grandma Inger was responsible for planning and preparing food. In the same way, it wasn’t the case that grandma Inger didn’t earn money for the family. She worked most of her married life as an assistant nurse.

Buying food was a large part of the family’s expenses. There was a lot to gain from cooking in a price-conscious way. The big challenge was making low cost food and still having enough food, tasty food and healthy food. A home economics school was the place to learn this. Good family finances, moderation and hygiene were central values at the school. In 1958, in Norway, over 40% of the expenses of an average family consisted of food, alcohol and tobacco. By the end of the 1990s, this proportion had fallen to 15%. A housewife that could cook good food from fish, especially cheap fish such as herring and pollock, who knew how to transform liver into nutritious and tasty food and who could make delicious everyday food from inexpensive vegetables, such as rutabaga, carrots and potatoes, could save the family a lot of money. Of course, it was also important to be careful with the size of the portions. Gluttony was a vice.

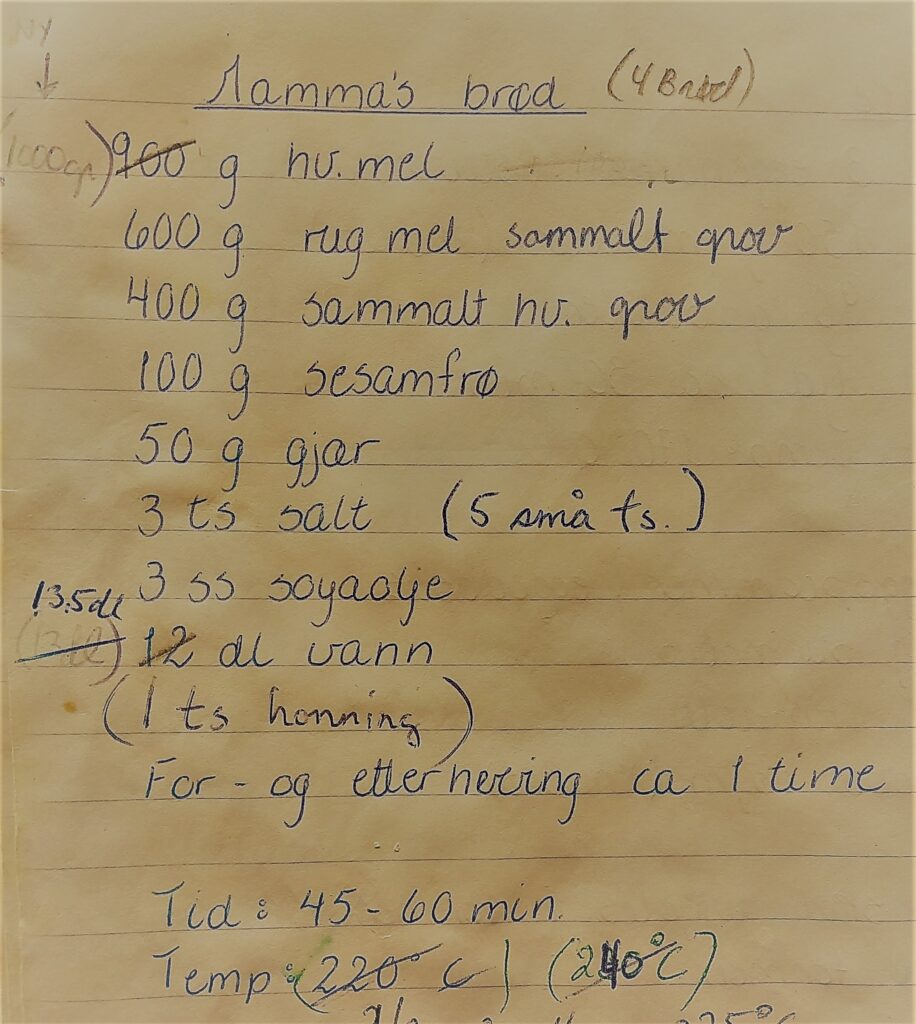

Grandma Inger baked all the bread for the household herself. My mouth waters thinking about her freshly baked bread with “American Ham” and gouda cheese or with scrambled eggs with smoked salmon. On baking day, there was always a treat in the evening. Grandma Inger and grandpa Terje would also pick berries in the forrest in the summer and grow the most delicious potatoes in their garden. Grandma Inger herself even grew up having chickens in their city garden in Bergen. The chickens were part of the family. Of course, they had to join the family on their summer vacations. Summer vacation meant a couple of weeks at their summer cabin just outside Bergen. At the time, the family didn’t have a car, so that meant bringing all the chickens in cages on the bus. I would have loved to have seen that. The bus ride was about an hour. They must have been a spectacle.

Grandma Inger’s bread

900 grams (30 oz) wheat flour

600 grams (20 oz) ground whole grain rye flour

400 grams (15 oz) ground whole grain wheat flour

100 grams (3.5 oz) unhulled sesame seeds

50 grams (2 oz) fresh yeat or one pack (1 oz) dry yeast

15 milliliter (3 teaspoons) salt

45 milliliter (3 tablespoons) oil. I use extra vergin olive oil, but soya oil is fine.

Mix to a fairly loose dough. Let it rise for 45 minutes

Divide into 3 if you have 2 liter (8 cup) bread forms or 4 if you have 1 1/2 liter (6 cup) bread forms. Bake the bread on your counter with oil and not flour. Grease the bread forms with real butter. This is important for the traditional taste.

Let the bread rise for 45 minutes in their forms with a towel over

Put the bread carefully in the oven and bake 220-230 degrees Celcius (430 Fahrenheit) for 45 minutes and take the bread out of their forms and bring bring back in the oven for an additional 15 minutes for perfect crust. Handle the bread with care. The bread should have a fairly dark color on the crust.

I have a certificate as a chef and I have handwritten several cookbooks for myself and for others. Both the large binders from my time as a chefs apprentice are handwritten. Nevertheless, it is the cookbook that was started by my wife Eva in 1985, with which I have the closest relationship. It has become our main joint cookbook through our 34 years of marriage. This cookbook carries with it a large part of our identity and history. Both Eva and I grew up with mothers who had their own handwritten cookbooks. When we read these, we can tell you a lot of interesting and funny family history. Most of the recipes can be roughly dated and reflect the era they were written.

Some of the best recipes are still used often even after so many years. Some recipes have simply expired for a variety of reasons. For example, we would like to make Grandma Inger’s pan-fried mini herring, but small herring (12-15cm) is simply impossible to get hold of here in the east of Norway. I have memories of Grandma Inger sitting in the kitchen at the gray table made of durable respatex. She would sit on one of the tubular steel chairs from the 1960s upholstered in red skai. She would filet the tiny herring with a small knife and tweezers. The recipe consists of opening and cleaning two small herrings for each “burger”. The head was removed and the whole herring was unfolded. It was then freed from all its bones and kept in one piece with the skin on. One herring filet was placed at the bottom and one on top. Between them, they were filled with pickled beetroot, sour cream, chives, salt and pepper. The “herring burgers” were dipped in flour and fried in real butter on both sides. A family of four would eat roughly three herring burgers each. That meant that grandma Inger had to prepare at least 24 tiny herring for just one meal. It is a job that requires good eyesight. The dish was served with lovely potatoes from the garden. It was a heavenly meal.

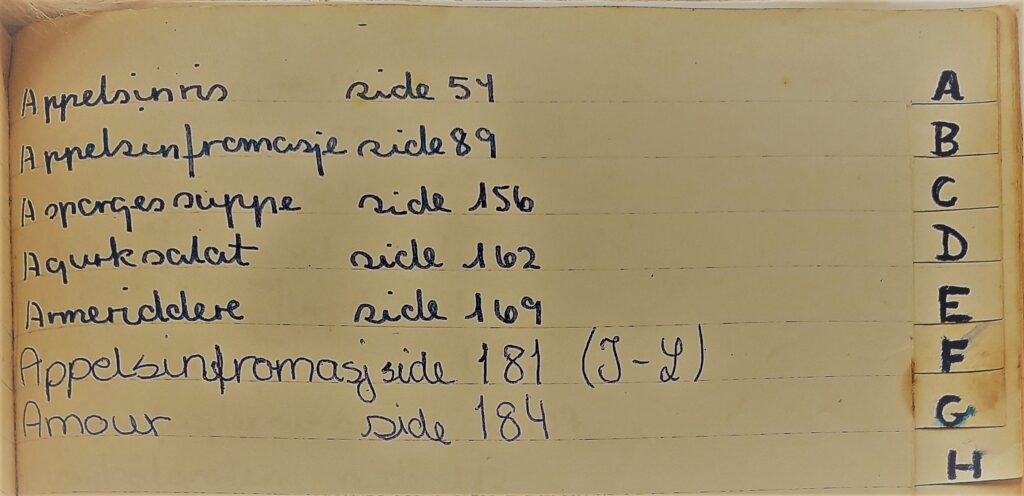

I had a kind of awareness of the potential importance of cookbooks from an early age. Before I turned fourteen, I started collecting and writing down grandma Aslaug’s recipes. My wife Eva was only sixteen when she started her own cookbook. Eva’s cookbook is made in the same way as her mothers cookbook from home economics school. In the back of the book, Eva has neatly cut out an index from A to Z. The index is worth the trouble because it means that we don’t have to leaf through the entire cookbook every time we need to find a recipe. After 39 years, the cookbook has 252 recipes. Most of them are still in use.

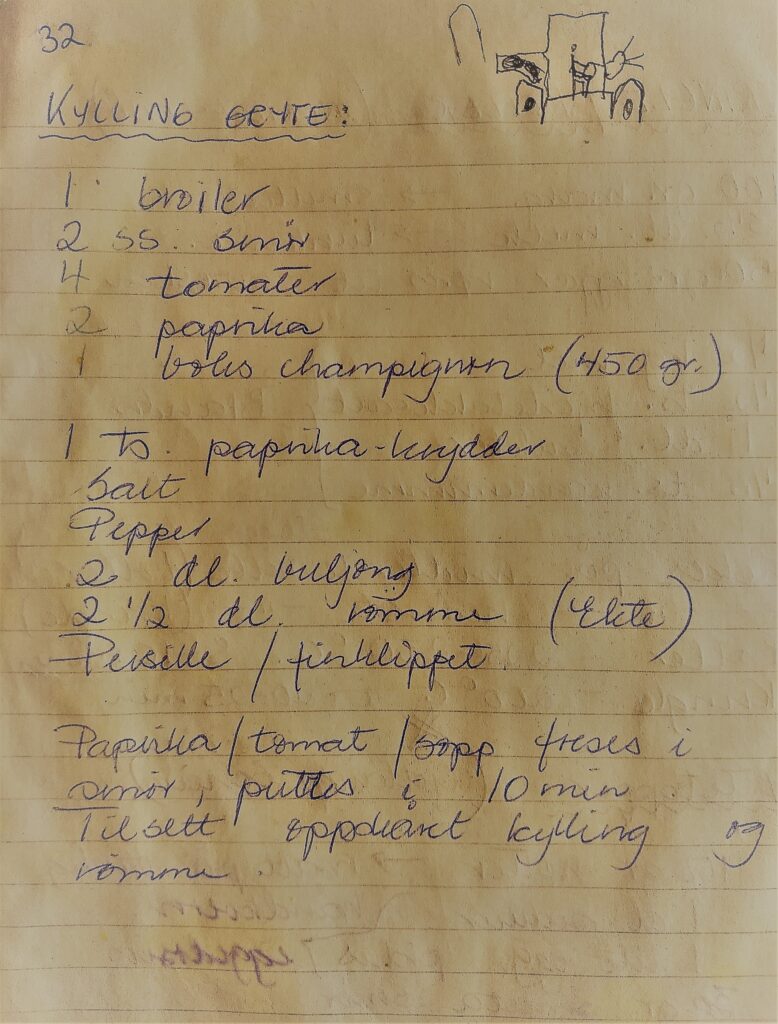

A recipe that has followed the family since the early 1980s is my aunt Kari’s chicken casserole. At the time, this was an exotic tomato-based chicken dish with both paprika (bell pepper) and sour cream. Everyone likes this dish. We still make it regularly. We now use olive oil instead of butter, fresh champignons instead of canned, 1 tablespoon of wine vinegar instead of broth, twice as much paprika and also add a whole squash in suitable pieces. In the summer, it is served with finely chopped raw summer cabbage, just as it was served at aunt Kari’s the first time.

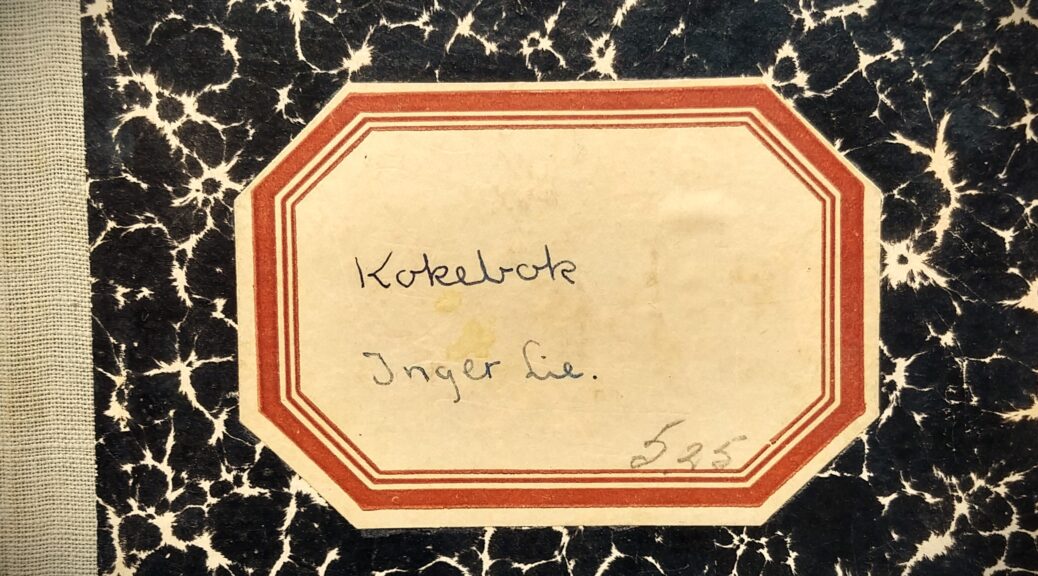

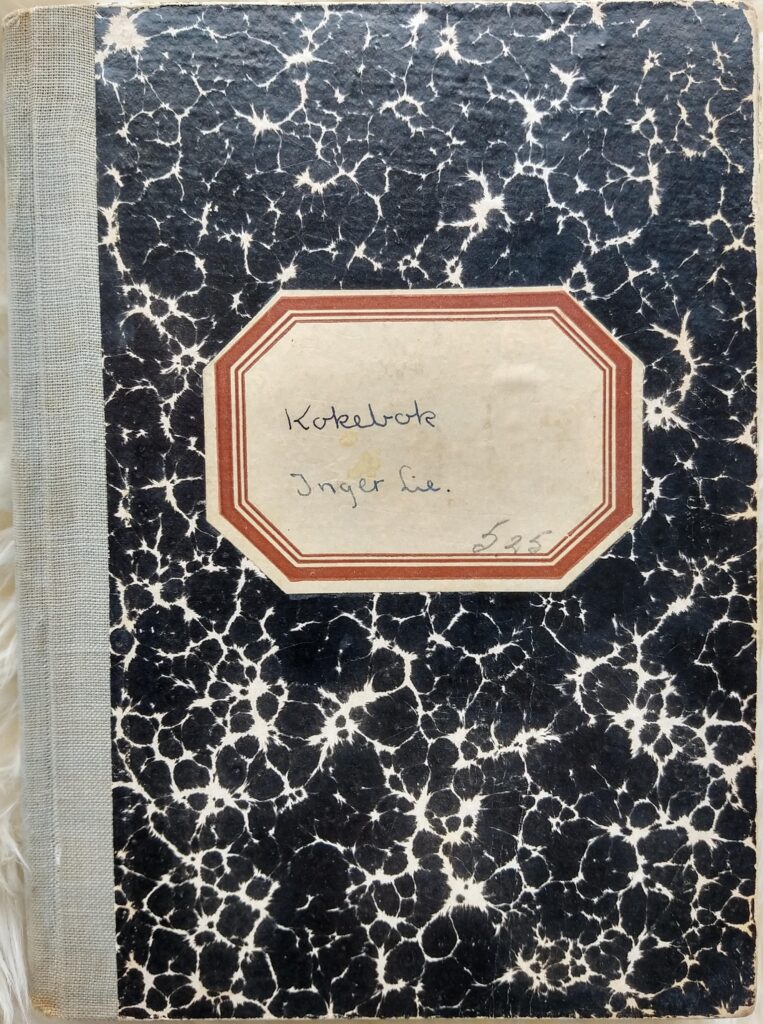

Grandma Ingers cookbook is written in ink. The ink is not completely waterproof and has given the book a very special appearance. The book gives an insight into handwriting skills at the end of the 1950s and shows a housewife profession that is no longer what it once was. I do not want the housewife profession to re-emerge in the form it once had, but I think that many young families could benefit from acquiring some of the skills that belonged to this role. In any case, I know that our own family has benefited greatly from having learned household economics and moderate, sustainable consumption. Our ancestors probably wouldn’t call us moderate, but we have learned to appreciate eating leftovers, using short-traveled food and we are happy that there is a certain economic thought behind the daily food planning. We have also incorporated habits where cooking from scratch feels natural. Grandma Inger’s cookbook could strengthen the wallets and health of many students and families.

We in the family often talk about the recipes that are lost forever. We remember wonderful dinner dishes, desserts and cakes that we will never taste again. We wish that grandmother Margot, great-grandmother Signe, grandmother Aadel and many other grandmothers had left behind a handwritten cookbook.

References

Grandma Inger’s cookbook started in 1958

Grandma Liv’s cookbook started in 1967

Eva Daae Kversøy’s cookbook (maiden name Ryngøye) started in 1985

Some references can be found in blue lettering. This is always a link.

Photos

All photos in this column were taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy except for the the photo of the minced meat recipe that was taken by my brother Runar Kversøy.

8 thoughts on “Point to Paper – Grandma’s handwritten cookbook and her famous Norwegian meatballs”

Need english

Hi Sonia, does “Need english” mean that you would like all the mentioned recipes in english?

I very much enjoyed this article. Reminded me so much of everything I learned from my tanter in Gausdal when I was lucky enough to live on the family farm for a year 1969/70 (I was 12/13). I loved it so much I came back 10 years later and attended Kokk og Servitoer linje at the newly opened Gausdal Videregaaende Skole – kind of a “modern” version of husmorskole, more geared to professional careers. I wrote all the recipes in notebooks as well that looked exactly like the black & white one in your column and I still have them. Those two years were the best years of my life. I have been back to Gausdal many times since and still read, write and speak Norwegian pretty fluently.

Tack så mycket! I so enjoyed reading this cookbook recipe. I don’t speak any Norska bara lite svenska. Truly a keepsake for you to be forever treasured.

Hi Diane, Swedish is fine with us as well. I have family and friends in Sweden and we share many of the same food traditions. Best regards Kjartan

Hi Kristi, I am so happy you liked the story. We have the same training then. I took the “Kokk og Servitørlinje” in 1991 at Oslo Kokk og Stuertskole. We had a very traditional training and we made the best fishcakes and Wienerstang. I will share more recipes in the future. Best regards Kjartan

Thank you for sharing your wonderful family story.

Hi Dale, thank you for your comment. My little stories are often about the family members that is no longer with us. It is a nice way of keeping their memory alive. Best regards Kjartan