Point to Paper – Grandpa Shaved with a Straight Razor and wrote with a pencil made of slate

Grandpa Walther grew up in Eastern Norway. He shaved with a straight razor. For him, being able to sharpen a blade that could cut facial hair was the mark of a man. I often wonder about things that once were common in Norway and suddenly became alien. Many things that were in everyday use for decades, generations and centuries have become obsolete and strange. Many things that were common in my grandpa’s childhood and youth in the 1910s and 1920s are strangely forgotten. A lot of things that were part of everyday life in my mother’s childhood and youth in the 1940s and 1950s seem excotic today. Even things that were completely normal in my own childhood and youth in the 1970s and 1980s are incomprehencible to a young person in 2024.

Grandpa wrote with a fountain pen. He also used a pencil. The pencils were sharpened and used until they could no longer be held. Grandpa even had a pencil extender. It made it possible for him to use the pencils an extra inch or two. When was the last time you saw a real pencil stub? It’s a rare thing today. Moderation was important to grandfather and most of his contemporaries. Few could afford anything else.

Grandpa Walther shaved with a razor. He kept it sharp with a leather strap. The razor was made to last at least a lifetime or two. He cut grass with a scythe. There was nothing strange about that at the time. He could handle a horse and wagon. This was something he did every day. It would have been impossible to run a farm without a horse. As a young man he joined the army. In an early period of his military career he even had to bring his own horse to work. He chose a life in the military. He eventually became an army engineer and an officer.

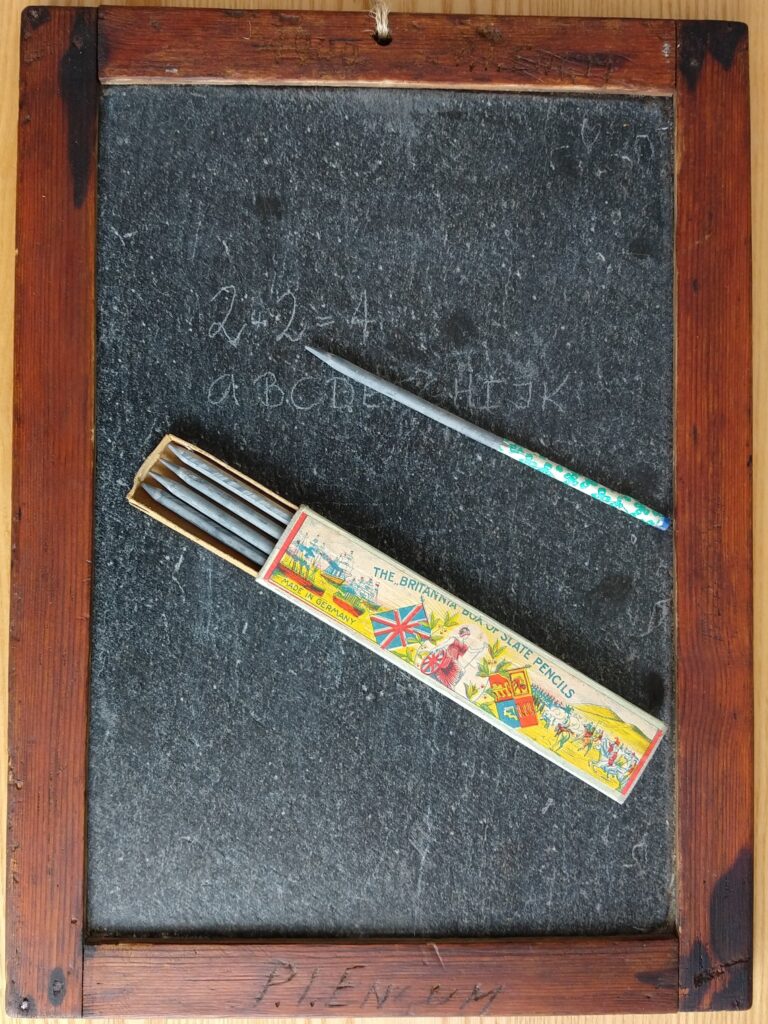

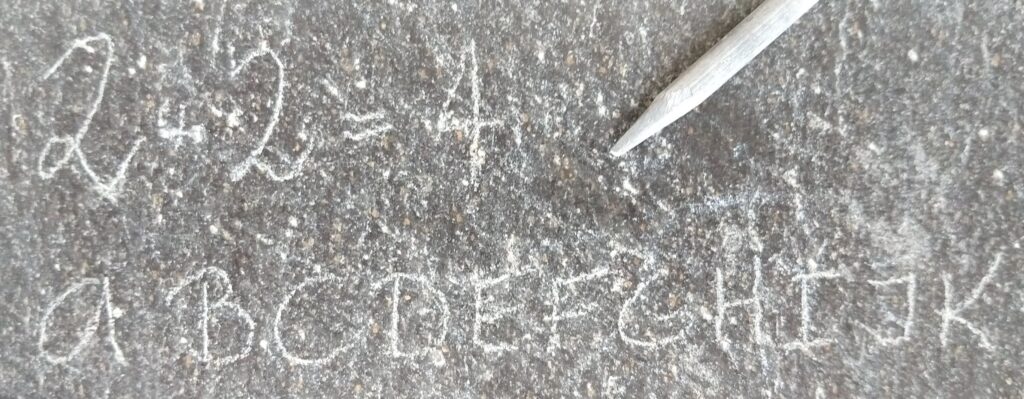

Grandpa often told us about a bad memory from his first years in primary school. He had to write with a slate pencil on a slightly harder slate board. Grandpa, who was born in 1906, went to an ordinary Norwegian primary school in Krokstadelva in Norway. If a slate pencil is completely unfamiliar to you, you are not alone. In the early 20th century, it was common for school children to use a board made of slate as a writing surface. On the board you would write with a pencil that was also made of slate. The pencil was made of softer slate than the board. With the pencil you could draw faint numbers and letters (see picture below). The slate board was like a blackboard. Just wash it off and you could use it again. The environmental footprint of school, in my grandfather’s time, was almost zero. My own slate board (picture above) is 118 years old and is still as good as new. You can actually still buy slate pencils.

Do you think chalk (also unusual in Norwegian schools today) makes an unpleasant sound when it is used on a blackboard? I can confirm that it is nothing compared to a slate pencil screeching and scratching dryly against on a slate board. This horrible sound was quite common in primary schools in my grandpa’s childhood. For the rest of his life, similar sounds always sent chills down Grandpa’s spine. Try to imagine day in and day out with a classroom filled with slate pencils scratching on slate boards. Everything was definitely not better before.

By making this early school experience a big deal you might think that grandpa lived an easy life. Far from it. He grew up in a family with a tight economy. He worked hard from an early age on their little farm. Grandpa was a Norwegian soldier during World War II and a prisoner of war from 1943 to 1945. I’m not saying that these things are comparable, but for grandpa, slate pencils on slate boards were an issue. He also disliked naked feet. Even as young children we were expected to wear socks on our feet when we ate breakfast together. I suppose this was understandable after living many years in close quarters with fellow soldiers.

My mother, mamma Liv (mama/mom in Norwegian), was born in 1943. She grew up in Gravdal and Sandviken in Bergen. She also wrote with a fountain pen and pencil at school. Just like grandpa (my mother’s father), she also used a dip pen in her first years at school. Every day she had to bring her own little bottle of ink to class (se picture above). The bottle fit perfectly in a hole in the desk. You just put the bottle in the hole, unscrewed the cap and dipped the pen through the hole in the desk and into the ink. Mamma Liv says that it was important to remove some of the ink from the nib on the edge of the ink bottle before writing. She did this to avoid inkblots on her writing paper. She and her friends would also sew together small pieces of fabric. The little bunch of fabric (se picture below) would be used to dry off any excess ink from the nib or other places. The fabric would always come from something that was worn out.

My mother also did other things that may seem a little strange today. In the late fifties, she and her sister Berit stiffened their petticoats with sugar water. You can imagine the mess. If you wanted to look pretty, you had to pay the price. Grandpa Walther and grandma Aslaug (my mother’s mother) would groan. They didn’t understand why the mess and the fuss was necessary, but they really had no choice but to accept that it was important to their young daughters. Teenage fashion crazes seldom leave much room for negotiation.

The family washed their hair once a week. That was a normal interval for most people at the time. Mamma Liv points out that grandma Aslaug was known for being meticulous about hygiene. Before they got a washing machine at home in the 1950s, all their clothes were washed by grandma in the laundry cellar using implements like a serrated washing board. The white laundry was also cooked in a brewer’s pan. The oven under the brewing pan had to be fired with wood. You can imagine grandma had a busy job at home. Her house was always in order, the clothes were clean and the food was made from scratch.

I also grew up with a pencil and a fountain pen. At that time, the ballpoint pen was probably the most common handwriting tool. I was only allowed to use a ballpoint pen at school after we moved back to Norway the year I started 5th grade. I had my first years at school in Antwerpen in Belgium, in Norfolk in Virginia and in London in Great Britain. Pencils and fountain pens were the preferred handwriting tools at school in all these countries. I always loved my fountain pens. For a period it was cool to wear a ballpoint pen hanging on a leather strap around the neck. In 1978, Parker came up with the Parker Swinger ballpoint pen. Many people I knew had one. I had a yellow one for many years.

The telephone in the picture above stood in the hallway at the house of my mother-in-law Inger and my father-in-law Terje. These gray phones were found in most homes in Norway in the 1960s, the 1970s and the 1980s. Once upon a time, it was my girlfriend Eva who spoke with me on this very phone. She has now been my wife for 34 years. It still feels odly natural to dial her number on a phone like this. The body remembers how it was done. I love the sound of the dial going back to the starting point. Six digits: 9 – 6 – 1 – 3 – 2 – 1. It’s like an old familiar song. I still have the phone. I sometimes dial her number on it. It is like travelling in time. Many good memories come to mind when I look at it and try it. I’m sorry I can’t use it anymore for making calls. It’s hard to understand that something that was so common seems so foreign today. The young people in the family just smile when they see this ancient contraption.

If you are born after 1990 you might be amused to know some more about the strange telephone habits in the 1970s and 1980s. I was only allowed to use the phone at home after five o’clock in the afternoon. Calling earlier in the day cost too much. A phone booth in the village centre was the only alternative. Have you ever stood outside a phone booth waiting to call your girlfriend? Have you ever stood in a phone booth and noticed that you are about to run out of coins? Have you ever tested how many friends you could fit into a telephone booth? These are all well known memories. They are part of how it was to be a child and a young person in the 1970s and 1980s.

We lived in the US in 1976-1977. In the house we lived in we had a yellow wall telephone with an extra long cord. We could take the phone and hold it between our head and our shoulder and walk around the room and do other things while talking. Fantastic! The cord could be stretched 12-15 feet. This was so unusual and strange that when we moved back home to Norway in the 1980s, and I told my friends about it, I gained a reputation for having a tendency to exaggerate.

Imagine that we lived for years with none or only one screen in the house. I’m not sure how many screens we have in our home today. Now I even carry a screen in my pocket every day. No one would have believed that in the 1980s. A gadget with a phone, a camera, a tv and a computer all in one?! With vivid pictures in color?! The size of a wallet?! That you can use to make video calls?! Without a cord?! Anyone fantasizing about a thing like that in the 1980s would be considered crazy. The one screen we had in our house the 1980s was a big fat 24 inch color TV. It needed service from a TV service guy often once a year. It had one channel. The channel was NRK (Norwegian National Broadcasting). We eventually experienced the wonderful revolution that enabled us to have a “cinema” at home. For a long period, renting movies on video and renting a VHS video player (moviebox) at the local video store, was typically something we did to enjoy ourselves on a Friday or a Saturday night.

A teacher I know, who works in primary school in Norway, says that she has pupils who have never seen banknotes or even coins. Currently we pay mostly by card in Norway. Cash is no longer king. Checkbooks have become a strange thing of the past and banknotes and coins are disappearing. It is becoming more and more common to pay with our smartphones or just tap with our card. In one of the advertisements during the pandemic, the grocery store Kiwi in Norway asked their customers to pay completely contactless. Paying without having any contact? That would have been hard to explain to someone living in the 1980s. Perhaps all this will also be strange in a few years.

Writing with by hand with ink has been common for at least 4,000 years. The pens were hand made from reed, bamboo, wood, copper and bronze. Quill pens made of feathers were the most common writing implement in Europe from the 5th century until the 19th century. The best were made from feathers from big birds. The most common were goose and turkey feathers. Mass-produced dip pens with metal nibs became common in the 1820s. They were just a further development of the feather quill. It was useful to have a nib that was more durable than one made of a feather. The fountain pen was also just an evolution of the dip pen. The fountain pen’s big advantage was that it carried its own ink and saved you all the dipping. For the first time in millenia, writing with a nib and ink has become uncommon. In the last 10 years, even writing by hand has started to become less and less common. I know young people who have almost no practice in writing by hand.

If we removed everything that was ever written by hand and in ink, we would almost have no history. Consider that everything of importance, until quite recently, was neatly written by hand. Writing implements and handwriting have been central to making society work. Private and public documents were actually handwritten until the typewriter was invented at the end of the 19th century. Many of these handwritten documents are still valid and are used to this day.

I think we lose something fundamental if handwriting ends up as a strange phenomenon from the past. For many, handwriting is one of the few activities that keep our hands doing a craft every day. Handwriting maintains daily practical contact between our heads and our hands. Pressing buttons on a keyboard is not the same. Every pencil and fountain pen that is available for use helps to keep handwriting alive. Hands are meant to create and do things. Hands can make our will happen. The head thinks. The hands do. To learn is to discover for yourself (Grendstad 1986). To master is to do it yourself (Kversøy 2015).

References

Grendstad, NM (1986). To learn is to discover . Oslo: Didakta

Kversøy, KS (2015). Method experiments with radical participation in education and research. Roskilde: Roskilde University – Free full version click here

Photos

All photos in this column were taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy unless otherwise stated.