Point to Paper – The Founders of the Norwegian Constitution have Living Descendants in the US. Are you maybe one of them?

Written by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy and Sandi Lee Bohle

Without a pen, paper and ink, there would have been no writing of the Norwegian Constitution in 1814. The 112 representatives brought the document to life by signing their names. Have you ever wondered who the signatures represented? One of them was my ancestor. He came from the County of Buskerud. He has living descendants both in Norway and in the US. Are you maybe one of them? My American 6th cousin Sandi Bohle and me, both sharing DNA from the same representative present at Eidsvoll, will here share a close-up story about him and some of his descendants.

You probably know that the Norwegian Contitution was born on the 17th of May 1814. Did you also know that it is the second oldest written Constitution in the world still in existence? The Constitution was originally founded on the principles of the sovereignty of the people, the separation of powers and human rights.

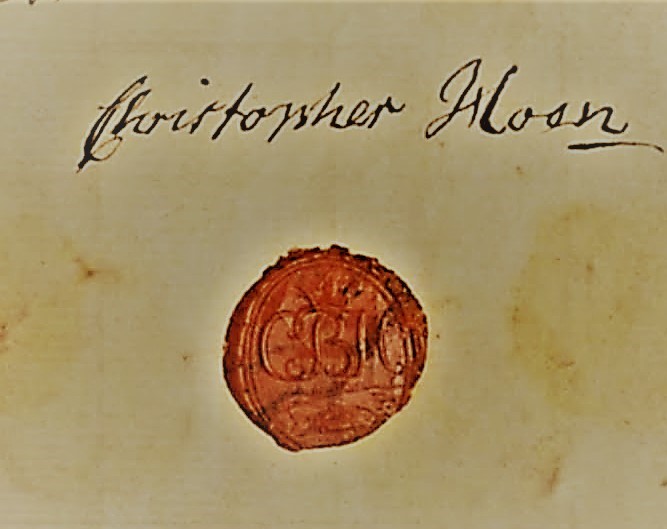

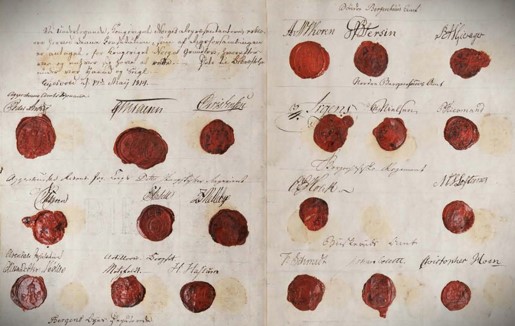

There were many great signatures in the document. Some are more readable than others. All were written in iron gall ink and with a quill. There is a high probability that they all used a hand cut goose feather to sign their names. The fountain pen had not been invented yet and the mass-produced and machine-made metal nib was yet to come (1822). The Constitution document was written on durable cotton paper. Today you are invited to get better acquainted with one of the men that signed the document. He has been referred to as a quick-witted, brave, cheerful and playful farmer from the parish of Eiker.

His full name was Christopher Borgersen Hoen. At the time he traveled to Eidsvoll, he was 10 years younger than I am now. He was 46 years old. His wife Anne was half a year older. Together they had eight children. The youngest boy was called Nils. He was 5 years old in the spring of 1814. Nils is my third great-grandfather. The eldest daughter was called Anne. She was 22. In addition, they had Ole age 7, Simon age 12, Borger age 14, Trine age 16, Børgine age 18, and Ingeborg age 20. Many years later, two of Borger’s grandsons would emigrate to America.

Christopher Borgersen Hoen was my fourth great-grandfather. He was one of the men present at Eidsvoll 210 years ago. His name and his lacquer seal are still clearly legible on the original Constitution document. However, no one knows what he looked like. According to a rumor, Christopher was not a fan of selfies. There exists a photograph that some say could be Christopher, but that is a demanding claim. Norway was a seafaring nation and admittedly received daguerreotypes (early versions of photographs) as early as 1841, but that would mean that the alleged picture of Christopher was one of the very first to be taken in Norway. In that case, it was taken at the earliest when Christopher was 73 years old. I don’t think the picture in question shows a man of 73. If there ever existed a picture of Christopher, I think it must have been painted. The story I was told growing up was that he thought he was too ugly to be painted. I have also been told it was because he had a face injury. He is said to have damaged his face and became blind on one eye after a fight with a horse.

I doubt that this version tells the whole truth. There have been several ancestors in my family that did not like to have their picture taken. I also have relatives who would have a hard time sitting still long enough to have their portrait painted. Christopher was a busy and impatiend man. Maybe he just never got around to it. I simply think that Christopher would have shrugged if someone suggested painting a portrait of him. He probably would have felt it was an act of vanity. Christopher was a follower of the Christian Haugean movement. Most Haugeans at the time frowned at the vice of vanity.

The family probably nagged Christopher for not being willing to have his portrait painted. His diversion tactic would have been to state that he was too ugly. It would have been part truth, part joke and part excuse. That is an explanation that resonates better with the “family spirit”. There are scientists that speculate that some fragments of memory might be inherited. I do not claim that I have inherited any of Christopher Hoen’s thoughts or feelings, but I experience kinship when I am together with my relatives. We have similar ways of being, thinking and reacting. We have opinions, interests and aversions that are recognizable to each other. We are far from the same, but there certainly is a feeling of familiarity and recognition when we meet. I toy with the idea that some tiny fragments of Christopher’s “being” may have travelled with his genes through six generations and ended up in me.

By visiting Christopher’s mind and feelings in this way I can imagine the following: Christopher has just returned home from six hectic weeks at the Constitutional Assembly at Eidsvoll in 1814. He is sitting at the table with his wife and eight children. He’s ready for dinner. It’s a bright and warm evening at the end of May. Anne (his wife) says: “Dear Christopher, now that you have signed the Constitution, isn’t it time to have your portrait painted?” Christopher teases his wife with a loving and mischeavous smile and says: “Anne, you know I’m too ugly for that. I never understood why you chose to marry a troll like me.” His youngest son Nils, only five at the time, would have objected and said: “Daddy, I think you are beautiful.” All the older kids around the table would have smiled. They would have known it was typical for dad to say something like that.

Christopher Borgersen Hoen was a great farmer from Eiker. He was rich and powerful. Christopher wasn’t afraid of taking the reins. That reminds me of several people in the family. Christopher also had a heart for those in need. During the famine in Norway from 1807 to 1808, he was responsible for distributing food to the poor and the hungry. He also thought that people should be allowed to express their opinions. He even thought they should do it when their opinions were controversial. In 1741, the Conventicle Act was introduced in Norway. It set restrictions on lay people’s opportunity to preach without approval from the local parish priest. Despite the fact that it was a breach of the law, Hoen nevertheless arranged illegal meetings in his own home.

The famous Haugean preacher, Hans Nielsen Hauge, was visiting Christopher during the Christmas of 1798. Hoen was a prominent Haugean and supporter of the revivalist and lay minister. Hauge believed that God had challenged him to tell others about his Christian conviction. It was a conviction that was not always in line with the view of the official church. Hauge had experienced a spiritual awakening one day when he was standing in the field outside his home. The date was the 5th of April 1796. On the New Year’s Eve of 1798, just two and a half years later, he was Christopher’s guest. He was preaching in Christopher’s house that same evening. Hans Nielsen Hauge had a lot on his mind. Among other things, he was concerned that words do not create change. He believed that it is through actions that we make the world a better place. This was a language that suited Christopher. Christopher was a man of action.

Christopher took a big chance by letting a layman preach in his house. Some of the Christians in the village thought this was way past the limits of the acceptable. For this reason some of them had asked the parish priest Schmidt to be present and observe. Before Hauge even started preaching Schmidt warned him and asked if he was aware that he was about to break the law. Hauge replied that obeying God was more important than obeying people. Schmidt got angry and demanded that Hauge quit what he was doing. The guests supporting Hauge told the parish priest to be quiet. They were there to hear what Hauge had on his mind.

When Hauge was finished preaching, the parish priest rose from his seat. He claimed that what had been said was both inappropriate and illegal. He was particularly annoyed that Hauge had chosen to read from The Book of Revelation. Schmidt pointed out that The Book of Revelation was meant to be a closed book. Hauge countered by saying that if that was true, the book would not have been named The Book of Revelation. Sheriff Gram was present. He agreed with the parish priest. The sheriff decided to arrest Hauge for violating the Conventikkel Act. There was an uproar among those present (“tumultuous” – according to Schmidt). The supporters of Hauge were outraged with what was happening.

My great-great-great-great-grandfather Christopher was both smart and brave. He asked if he could have the honor of using his own horse and wagon to drive Hauge to jail. Christopher tricked the sheriff by taking his fastest horse. Before the sheriff understood what was happening, Christopher had transported Hauge outside the jurisdiction of the local law. The sheriff had no authority there. He had to accept that Hauge had gotten away with it. Christopher chose a solution that Hauge himself would not have chosen. Hans Nielsen Hauge was not a man that ran away from anything. He later went to jail exactly for that reason. Christopher also chose an action that few others could afford without getting in trouble. It says a lot about the power he had. Neither the sheriff nor any other person in power dared to mutter when Christopher made a decision.

I also think the situation was characterized by a good portion of testosterone. Sheriff Gram was only 20 years old and had been teased by Christopher just a few days earlier. The parish priest Schmidt and Hans Nielsen Hauge were both 27. It was clear that this was a duel between two young religious men and their conflicting opinions. Christopher himself was no more than 31. All this suggests that the tense atmosphere that night also was a showdown between four young men with power.

Sixteen years later, Christopher Borgersen Hoen was one of those chosen to travel to Eidsvoll to create and sign the Norwegian Constitution. He was one of the representatives from the County of Buskerud. He belonged to the Independent party. Christopher was chosen because of his position in the local community. I expect that there were several local citizens that felt uneasy about this. Not least his co-representative parish priest Schmidt. This was the same Schmidt that had demanded Hans Nielsen Hauge to be arrested at Christopher’s farm in 1798.

Nevertheless, Christopher and the parish priest Schmidt were lodged together at Lysaker farm while they worked on the Constitution. It seems they collaborated well. The farm was located a little under a mile from Eidsvoll. The other guests at the farm were the bailiff Johan Collett (his son Peter later married the famous writer Camilla Collett), the miner Paul Steenrup (who established the Kongsberg Weapons Factory in 1814 – among other names today known as Kongsberg Defence & Aerospace) and sheriff Ole Rasmussen Apenes. They were all among the 112 who worked together at Eidsvoll.

Christopher had to share a bed with Sheriff Apenes. He writes home to his wife about this. He writes it in a way that shows that this was not uncommon at the time. He claims that the guests at the farm had a good time together. Christopher brags about the food on the farm. In the letter to his wife, he writes (my translation to English): “(…) I wish God could grant that the poor and people in general all the necessary things in life, then we could better enjoy our abundance”. Christopher was aware of the need and unfairness in society and felt that he was privileged. The luxury at Lysaker farm would have tasted better if everyone was better off. Unfortunately, we know little about Christopher’s work in the Norwegian Constituent Assembly. What we do know, through a letter to his wife Anne, is that he had direct conversations with the Danish Prince Christian Frederik.

Both his son Borger and his grandson Olaus became members of the Norwegian Storting (The Norwegian Parliament). Borger was the driving force behind removing the Conventikkel Act. He finally made it happen 1842. That must have pleased Christopher Hoen in his older days. Borger also experienced that Scandinavia’s largest gold treasure from the Viking Age was found on his farm in 1834. The treasure consisted of no less than 5.5 pounds of pure gold. The grandson of Christopher, Olaus Børgersen Hoen Fjerdingstad, was a Member of Parliament from 1871 to 1876.

Christopher and his son Borger are both ancestors of many Norwegians living in the US today. My American 6th cousin Sandi Bohle recently wrote me a letter. Sandi has approved her story being shared in this article. She has also permitted me to share the picture above. Sandi, like me, is a direct a descendant of Christopher Borgersen Hoen. Sandi starts her letter by writing about his son Borger. Borger’s daughter Anne Christine married Johannes Knudsen Bjorhus in 1846 in the parish of Eiker. This is the same parish where Christopher’s farm was located and where the big showdown between the four young men took place in 1798. Anne Christine and Johannes had eight children. Two of their children, one named Christopher (after his great-grandfather) born in 1851, and one named Valdemar born in 1862, both emigrated to the US. Christopher landet in Port Huron in Michigan with the ship Hero in 1879. Port Huron saw the largest number of Norwegian immigrants who settled in America. Port Huron saw even larger numbers of Norwegian immigrants than those that arrived at Ellis Island in New York.

Christopher moved on to settle in Wisconsin where he homesteaded and began to farm. He married Ada Stafford and had four children. Valdemar (Sandi’s great-grandfather) met his future wife Emilie Nilson during his confirmation in his youth in Norway. Their first child, Anna Christine, was born the 23rd of November 1888 and tragically died just six months later. Valdemar had left for America on the 20th of April 1888 and never got to meet his newborn daughter. His wife Emilie finally left Norway for America on the 6th of May 1889. They settled in Weyerhaeuser, Wisconsin where they became farmers. Their children were also born in Weyerhaeuser. They had eight children together. Their second youngest daughter Anna Christine was born 1901. She was named after the child they lost. Anna Christine was to become Sandi’s grandmother. Valdemar and Emilie first moved to Harvey in Wells County in North Dakota to join his brother Christopher and his wife Ada. After some years there they moved to Weyerhaeuser. They eventually settled in Fargo in North Dakota.

Two of heir sons, Carl and Arthur, served in World War I on the frontlines in France. They were lucky and both made it home. Today the descendants of Christopher Borgersen Hoen are spread out across the Midwest and the Pacific Northwest. They are children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, great-great-grandchildren and great-great-great-grandchildren of the first settlers from these families. For many decades, there was an annual summer gathering of the Bjorhus clan. It became more sporadic as Sandi’s grandmother’s siblings died.

Sandi was past on the task of being the family genealogist after her grandmother Anna Bjorhus Rusten. They both heard the stories that had been passed down from generation to generation. Sandi now tries to preserve them as best she can. Sandi also learned the family recipes that had been passed down. She still cooks them to this day. Sandi and I might have to write another article about family heritage recipes preserved in America and Norway. Christopher Hoen’s descendants in America work as farmers, civil servants, teachers, social workers, politicians, Chef’s, a Pulitzer Prize nominated investigative journalist, a Trauma Therapist, and in many other occupations. They are all proud descendants of one of the founding fathers of the Norwegian Constitution.

Christopher was a man with a plan. I think he even chose his death day carefully. Christopher Borgersen Hoen died on the 17th of May 1845. He was 77 years old. He is buried at Haug cemetery. His grave is just a short walk from his old farm.

References

Peder Berge (1950). Hans Nielsen Hauge and Eikerbygdene. Retrieved the 4th of May 2020 from https://eikerarkiv.no/hans-nilsen-hauge-og-eikerbygdene/ Eikerminne page 7-14

lokalhistoriewiki.no. Christopher Borgersen Hoen. Retrieved 4 May 2020 from https://lokalhistoriewiki.no/wiki/Christopher_Borgersen_Hoen

Eidsvoll 1814 (u.å.). Christopher Borgersen Hoen. Retrieved 4 May 2020 from https://eidsvoll1814.no/christopher-borgersen-hoen

Tore Hæg (2014). Christopher Borgersøn Hoen, 1767-1845 : gårdbruker og Eidsvollsmann.

Oslo: ISBN 987-82-999400-2-3

Illustrations and pictures

The pictures in this article are shared by Sandi Bohle, taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy, borrowed from Wikipedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=grunnloven&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image and from images of the Constitutional document https://www.stortinget.no/no/Stortinget-og-demokratiet/Grunnloven/Dokumentet-Grunnloven-av-17-mai-1814/ .

2 thoughts on “Point to Paper – The Founders of the Norwegian Constitution have Living Descendants in the US. Are you maybe one of them?”

Loved your story. I understand that I too am a descendent of a constitution signer but I need to do more research to come up with the name.

Hi Lorrie,

I am sorry this answer is far too late, but if you receive this answer please take contact on email kjartansk@gmail.com and maybe we can work out who your ancestor was. Best regards Kjartan Skogly Kversøy