Point to Paper – The watchmaker, the linendraper, the poet, the calf and an abundance of people named John

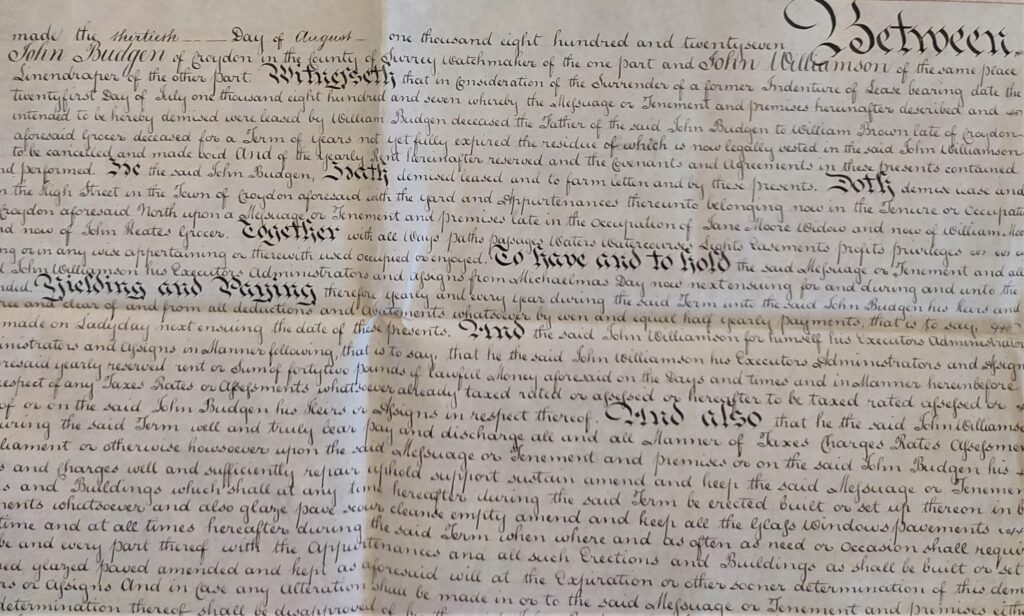

In the summer of 1827, John Williamson decided to take a bold leap into the future. He wanted to establish his own business. Williamson was a linendraper. He had found a great property. It was in an ideal location for what he was planning.

Another John, the watchmaker John Budgen, had inherited an estate from his recently deceased father. The property was located in Croydon just south of London. The buildings were located on High Street. High Street was central and busy. It was important to maintain good activity on the large premises. The property had good financial opportunities if they were used sensibly. At present it was less busy than he could have wished. Budgen had therefore decided to rent out the property.

Croydon was then, as now, an important trading centre. As early as 1276, it received rights from the king to hold a weekly market. Croydon developed over time to become one of the most important market towns in North East Surrey. In the middle of the town was Croydon Palace. From the sixteenth century until 1781, Croydon Palace was the summer residence of the Archbishop. It was visited by both clergy and royalty. The palace was sold and became part of the city itself in 1781. The Archbishop moved to Addington Palace which is also in Croydon. Between 1807 and 1898, Addington Palace was home to six Archbishops. John Budgen’s fine city center property, which he now wanted to let out, was within the boundaries of the old Croydon Palace.

Budgen came from a long line of watchmakers. Both John himself, his father William and his uncle, also named John, were skilled in their profession. All of them were nevertheless somewhat in the shadow of their more famous grandfather, the great watchmaker and clockmaker Thomas Budgen.

Both Williamson and Budgen were craftsmen. They had both completed their apprenticeship in the trade they belonged to. It had allowed them to be accepted into a guild that protected both their trade and their titles. In this way, John Williamson had acquired the right to the title “Linendraper” (textile dealer) and John Budgen had acquired the right to the title “Watchmaker”.

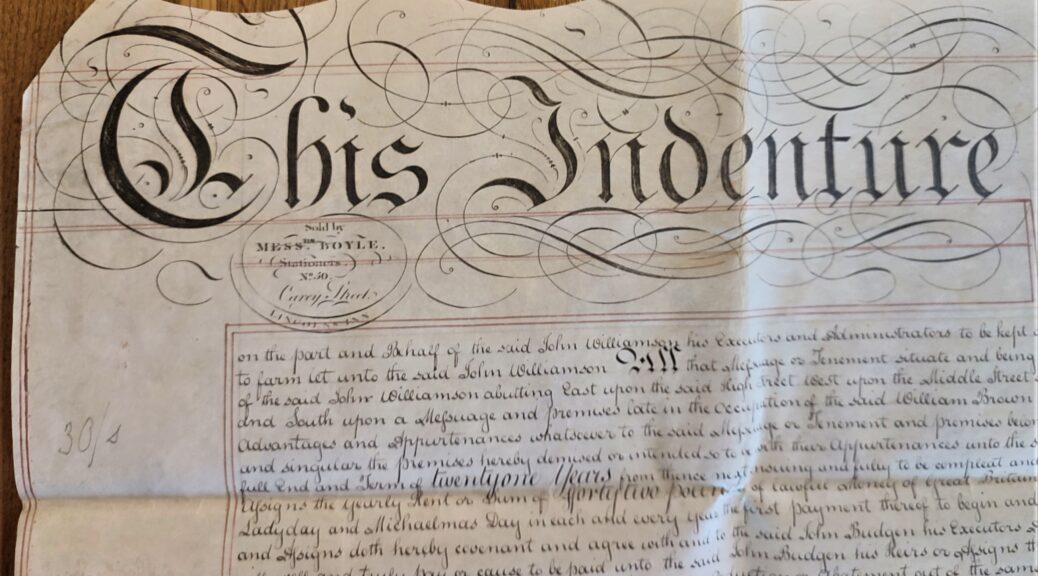

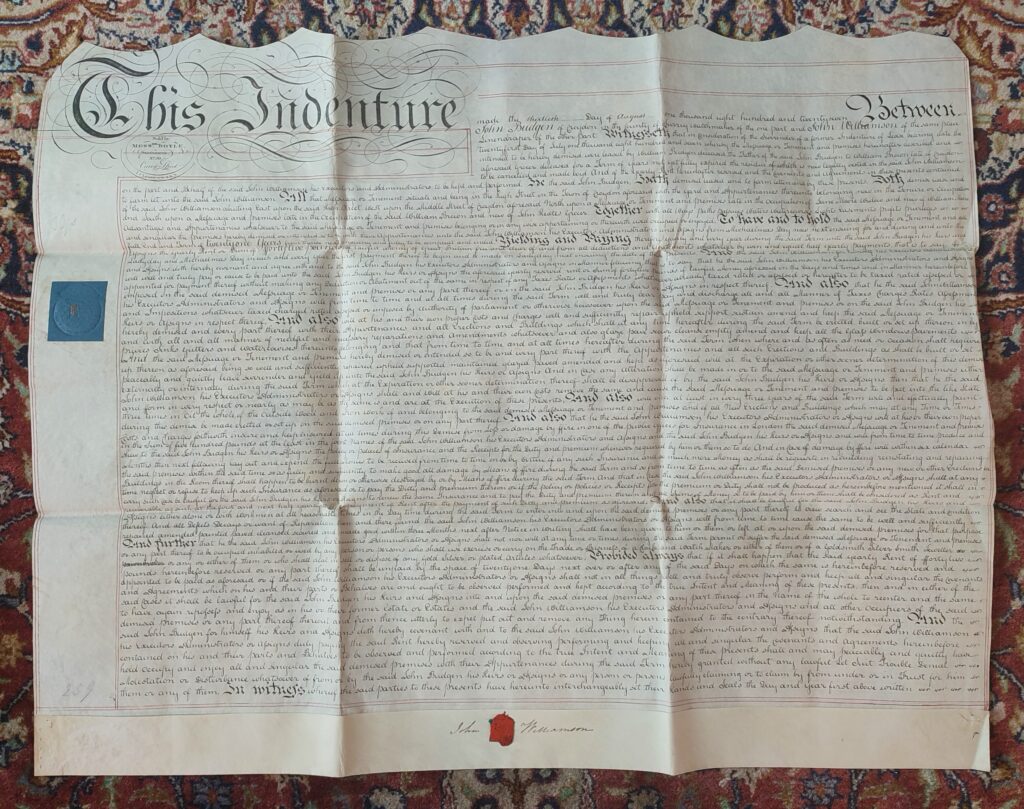

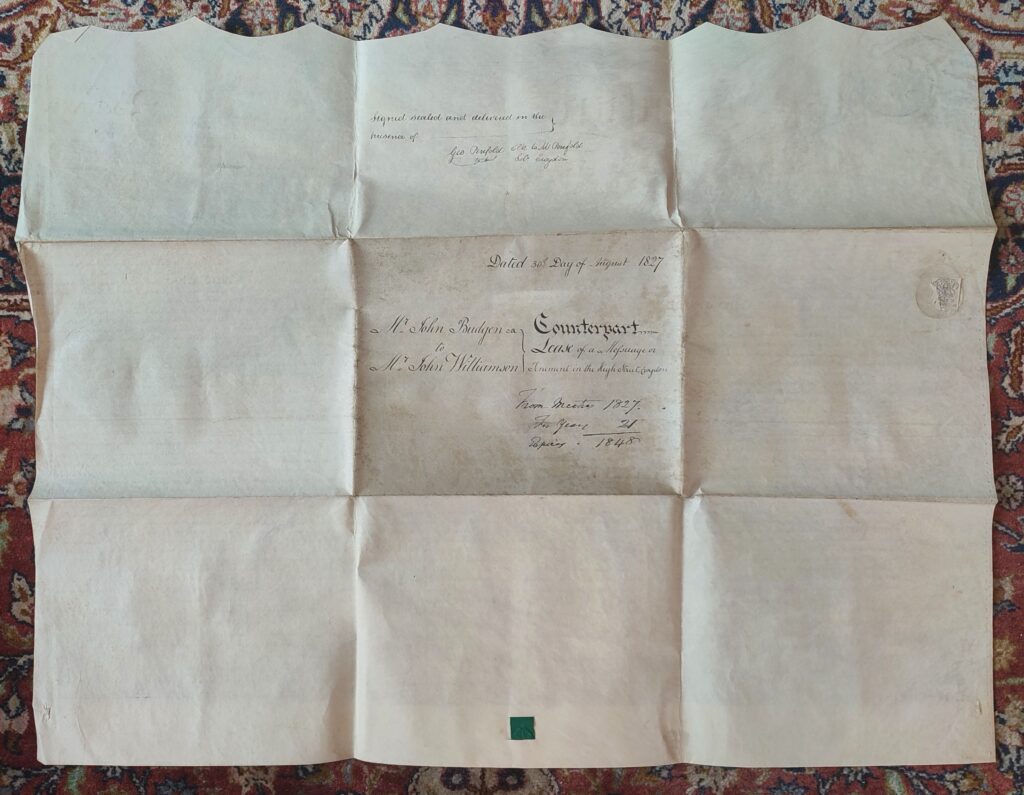

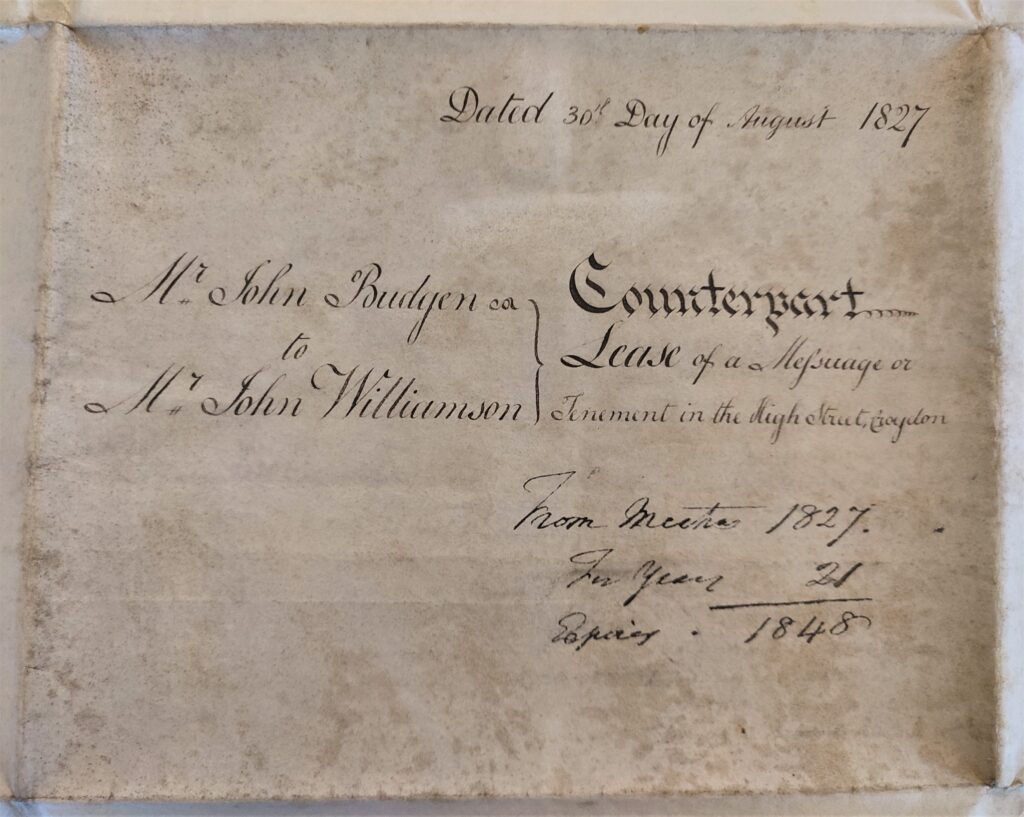

Budgen had offered to lease the property to Williamson for 21 years. They had agreed on an annual rent of £42. This corresponds to approximately £6000 in 2023. The rent was to be paid twice a year with one half on Ladyday (March 25th) and the other on Michaelmas Day (September 29th). According to the contract, Williamson also accepted a wide range of carefully specified obligations. The sinks, drains, gutters, windows and everything else needed to be kept in order. The property was supposed to stay in the same fine condition as when the lease was entered into. On the 30th of August 1827 the lease was signed with lawyer Geo Penfold Esquire present as awitness. The agreement was to last until the same date in 1848.

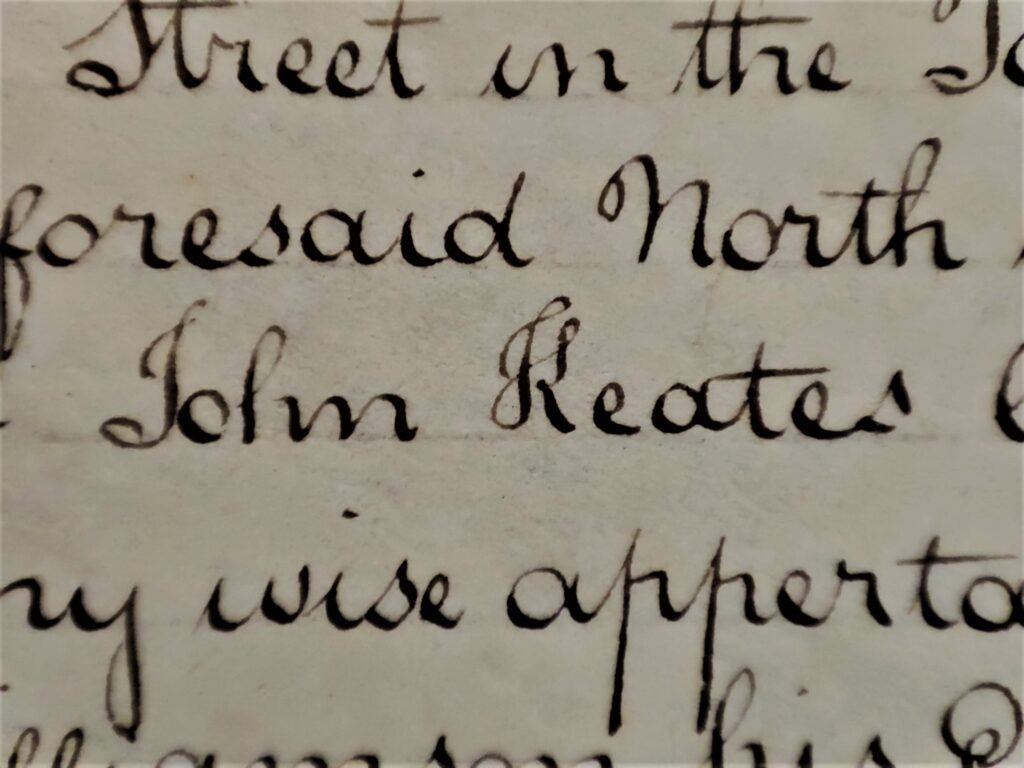

The description of the property’s location is in itself interesting. It is stated in the contract that the property is abutting to the east to High Street in Croydon, to the west to Middle Street, to the south to the neighbor Jane Moore, who was the widow of William Moore, and to the north to the neighbor William Brown, who was the successor of the merchant John Keats (another John).

I don’t think this is the famous poet John Keats, but it actually could be. If not, it is still interesting that two people with the same name existed within an short journey of each other at about the same time. The poet John Keats died in 1821. After his death, he became known and praised as one of the world’s great poets. During his lifetime, several of his works were strongly criticized and described as unsuitable for women. The poet John Keats died in Rome of tuberculosis and was buried there. He knew he was going to die and had planned what was to be written on the tombstone. Keats died young, only 25 years old, and the following is written on his tombstone:

This Grave contains all that was Mortal, of a YOUNG ENGLISH POET, Who, on his Death Bed, in the Bitterness of his Heart, at the Malicious Power of his Enemies, Desired these Words to be engraved on his Tomb Stone – Here lies One Whose Name was written in Water Feb 24th 1821

How do I know all this? It’s actually quite by chance. Neither Budgen nor Williamson were particularly famous people. There is really nothing unique about the agreement they entered into either. They would probably have been very surprised if they could have seen into the future. They would never have guessed that a Norwegian would write about them some day. 196 years later, in 2023, it happened. This year would have been as foreign and incomprehensible to them as the year 2218 is to me. The only reason I can write this story is the quality of the actual physical contract (indenture) they signed. Modern contracts would probably not withstand 200 years of storage. Neither the paper nor the printed ink is particularly durable on most of the printed texts of this kind we produce today.

We can only imagine what will happen to electronic contracts that are stored in the cloud and on hard drives using complicated technology. It is technology that we know goes out of date relatively quickly. I have “newer” information, both pictures, programs and text, stored on 1.44 MB floppy disks . As recently as 1996, it was estimated that there were five billion such floppy disks in use. They were introduced in 1986 and began to be phased out in 2003. Already in 2007, only 2% of new PCs had a drive that could read such disks. Today, floppy disks of this type are unreadable by most PCs. Most of the information that was once stored on them is already lost. A lot of our present history is surprisingly vulnerable.

In the 19th century, there was a different mentality when it came to durability. Many British contracts from this time were of an almost unfathomably high quality. The lease between Budgen and Williamson was handwritten in iron gall ink on animal skin “paper”. The quality was excellent.

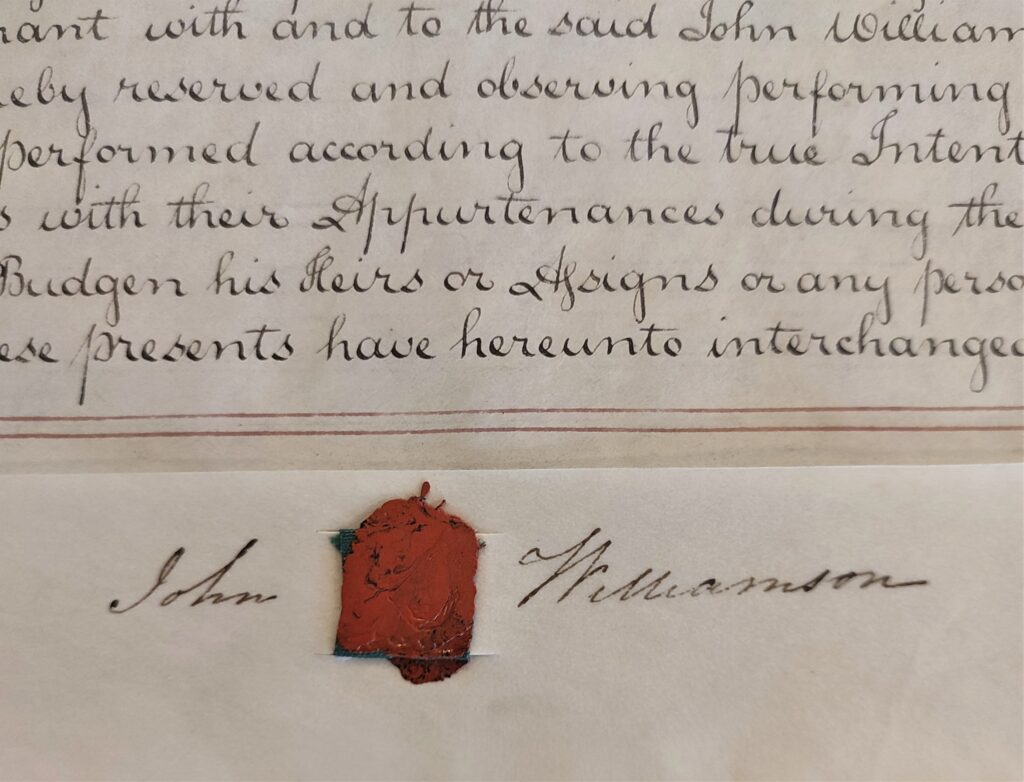

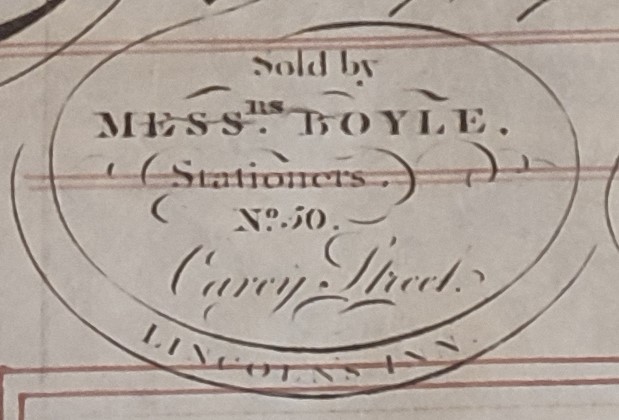

The “paper” itself was supplied by Messrs Boyle Stationers No.50 Carey Street Lincoln’s Inn. They were specialists in office supplies for law firms. The sheet on which the contract was written was specially produced for the purpose. The document was “Signed, sealed and delivered in the presence of Geo Penfold”. He was a solicitor in Croydon. The agreement is entitled “Indenture”. It refers to the wave pattern that was cut into the top of the contract. The wave pattern was cut through several copies of the same contract as a security measure. Only contracts that matched exactly were valid. All contracts were handwritten, so they were never 100% the same. With the help of this simple security feature, a wavy cut edge, it became more difficult to forge this type of contracts. In addition, the contract has a green silk ribbon. It is attached with a lacquer seal and laid through a fold in the paper. The lacquer seal and the signature belonged to John Williamson. Finally, there was a blue notary stamp with a public filing fee attached. In this case £1 and 10 shillings.

Animal skin “paper” is often called parchment. Often the term parchment is used uncritically for all types of animal skins including certain types of fine paper. Parchment is strictly speaking any type of animal skin that has been processed for the use of writing upon it, with the exception of calf animal skin. “Paper” made from calfskin is called vellum. The William Cowley company is the last company in the UK to produce parchment and vellum. Until 2016, vellum was used to print archival copies of new British laws. The reason was the superior quality and durability. There are, for example, good legible copies of religious texts written on vellum that are over 2,000 years old. The company William Cowley is careful to point out that no animals are bred specifically to become parchment or vellum. All their material comes from animals that are already involved in either meat production, wool production and/or the production of dairy products. The processing is environmentally friendly and carried out with traditional lye as a central ingredient.

Finally, I must point to the handwriting. Study the pictures carefully. The writing is beautiful, clear and easy to read. Who wrote the document remains a secret. The lawyer probably had a dedicated scribe employed. The lawyer Geo Penfold and the tenant John Williamson are the only ones who have signed this copy of the contract. None of their handwriting matches the main handwriting of the contract. The contract I have is referred to as a “counterpart”, so it seems this is John Budgen’s own copy. I assume then that John Williamson had a contract with the same content and wave pattern but signed by John Budgen. I welcome input from readers who know more about this form of contract than I do.

I don’t actually know if the contract between Budgen and Williamson was written on parchment or vellum, but let’s play with the idea that it’s vellum. Perhaps the skin came from a calf that had been unlucky enough to not survive its own birth. Calfskins from just such calves were considered the most exclusive starting point for the production of high quality vellum. The calf did not become a cow or an ox. It never produced milk. It didn’t turn into steak or end up as an armchair. This calf became something more. It was transformed into something that takes care of history. With the help of its skin, the name and the history of a whole series of people, has been preserved for 195 years. Perhaps the text can even be read in 2000 years. I take å deep bow on behalf of the calf.

Photos: All photos are taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy

Sources: The information for this post is mainly taken from the document itself and is supported with more or less reliable information from Wikipedia

One thought on “Point to Paper – The watchmaker, the linendraper, the poet, the calf and an abundance of people named John”

Very good