The two brothers who started a pencil factory each

This article was originally published in Norwegian at Pennen er mektigere, on May 8, 2022.

In this article you will read about fish theft, arson, tax and insurance fraud. It’s about the demolition of a district in the capital, and about being on the wrong side in a war. We will meet a non-commissioned officer, teacher, organist, writer, merchant and factory owner. Yes, and an opera singer! And we will hear about a couple of brothers from Senja who moved to Oslo and each started their own pencil factory.

The brothers Jens Hagerup Nikolaisen Vassvik and Aksel Emil Vassvik were born respectively on September 22, 1884 and May 29, 1893 on Tranøy, on the south tip of Senja, a big island in the far north of Norway. Their parents’ names were Nicolai and Ingeborg Jensen, and the two brothers were part of a group of nine or ten siblings. Some of the siblings (unclear how many, although one source suggests two brothers and two sisters) emigrated to America around the turn of the century.

The first historical sources I have been able to find that mention the brothers are from 1911. In October of this year, two newspapers – Bodø Tidende and Helgelands Blad – wrote about three guys from Tranøy who had been charged with stealing more than two thousand stockfish that were hanging to dry after that year’s fishing season in Lofoten. The three were the brothers Jens, who was then 27 years old, Norman (25 years old) and Aksel (18 years old). In the trial it emerged that the three had not stolen the fish directly, but that they had met two other men who sold them the stolen fish at a cheap price. The eldest brother Jens explained in court that they had bought the fish, and planned to sell it on at a profit, and they hadn’t considered that they might be breaking the law. Helgelands Blad referred to Hagerup’s explanation:

When this was cheap compared to the normal prices, they jumped at the chance, and it did not occur to them that there could be something suspicious about the offer. The fishing was good, and the man in question had stated as an additional reason that they would soon recoup the loss by selling so cheaply. At the time of the count, there were 2024 fish in the lot. On the journey home they had come to talk about the fact that it was a bit strange that the person in question had sold to them, instead of a certified trader.

The Vassvik brothers were eventually convicted of trafficking stolen goods, and punished with, respectively, 45, 30 and 24 days of suspended prison.

We will return to Aksel later in this post, but first we will take a closer look at Jens.

A man of many talents

Jens Hagerup was originally trained as a non-commissioned officer in the army, but in 1910 he graduated from Tromsø public teacher training school. He also studied for a year in Copenhagen (Denmark), and then worked as a teacher several places in Norway during the next ten years. He also worked a bit as an organ player, when there was a need for it, and in 1912 he started a business in Lyngen, in the north of Norway, with one of his brothers. It lasted for about a year before the company shut down, and Jens moved again.

In 1919, Hagerup was a little further south, in Glomfjord in Meløy, where he started the company Hagerup Vassvik & Co., together with Emil Ingebrigtsen. The company aimed to run a merchant trade in Glomfjord. This business was also a short-lived affair. Two years later, Hagerup lived in the southern part of Norway, in Langesund, where he worked as a teacher. In the summer of 1921, his house burned down under mysterious circumstances. The cause of the fire was never clarified, and Hagerup was paid an insurance sum of NOK 42,000. He used this money to move north again, this time to Harstad, where he started a textile shop under the company name J. Hagerup & Co. Aktieselskap (limited liability company).

Hagerup was also an author. He published his debut novel, “Susanna” in 1922. The book depicted fishing life in Senja, and received a lot of attention for the romantic way in which the Sami (the indigenous people) were described. Jens Hagerup wrote several books throughout the 1920s, which were mostly well received.

Shop fire

Hagerup moved his shop into his own building in Harstad in September 1922, and on the night of November 26 of the same year, a fire broke out in the premises. Fire crews were able to tackle the fire before it spread, but most of the shop inventory was completely destroyed. Hagerup never rebuilt, and he took his family with him and moved to Oslo (which was called Kristiania back then) shortly afterwards.

On November 13, 1923, he was arrested in Kristiania, charged with “insurance fraud, arson, embezzlement, fraud and forgery” in connection with the fire the previous year. The trial took place in Harstad in the winter of 1924, and became a rather big affair. During a two-week trial, a total of 48 witnesses testified in the case.

The evidence strongly suggested that the fire was the result of arson. There had been no fire in the oven when the fire started, and an expert witness who had examined the electrical system in the building had found nothing wrong with it. There were no signs of a break-in. Several witnesses had noticed that there were remarkably little goods in the store in the days leading up to the fire, and it was speculated whether Hagerup had moved much of the stock to prepare for a fire. Hagerup had taken the cash book and goods register home with him, but had left the account book (the general ledger) in the store. Investigators found no trace of the book after the fire, although they found many other paper scraps that hadn’t completely burned down. Traces of kerosene were found in several places on the floor of the room where the fire had started.

Hagerup himself had an alibi. He had left the shop a few hours before the fire to visit a relative in Kvæfjord. One of the investigators launched a theory that Hagerup could have lit a candle before he left, and in that way rigged a fire that would start when the candle burned down a good while later. There was also suspicion that Hagerup had cheated on the amounts in the cash book over a long period of time. It was suggested that the book was newer than the defendant said it was, and that he had made it after the fire. He was also accused of having lied about the values of the shop inventory to the insurance company, in order to be paid more money than he was entitled to.

There were a lot of circumstantial evidence, but no clear conclusion in the case, and on March 10, 1924, Jens Hagerup was acquitted on all counts.

The whole case was a burden for Hagerup, and something he was unable to put behind him for several years. In 1926, he published the book “Brenning” (“Burning”), which is about a merchant who is accused of burning down his own shop. Here, Hagerup went so far as to give some of the characters the same names as the corresponding people who had been involved in his own fire case a few years earlier. Hagerup was criticized for this in the media, and many believed that as a writer he should have taken the high road, instead of bullying people who had just done their jobs.

“Are pencils manufactured in Norway?”

On January 22, 1932, in the column “Spørsmaalskassen” in the newspaper Øvre Smalalenene, there was a question about whether pencils were manufactured in Norway.

Brødrene Moltzay Papirhandel og Industri, a paper goods merchant in Oslo, answered the question in the newspaper:

No Norwegian pencil factory exists and it is unlikely to become a lucrative business. The modern pencil industry requires large-scale operations of such dimensions that the three global companies A.W. Faber, Johann Faber and L. & C. Hardtmuth have formed a community of interests in order to make the operation profitable.

Norway has none of the necessary raw materials, neither the wood nor the graphite, and has no conditions for a lucrative operation. Even if, with the help of tariff increases, one would try to secure domestic consumption, one would have to compete on the world market with surplus production.

Just a couple of months later, Jens Hagerup was to put the statements of the Moltzay Brothers to shame.

The Norwegian Pencil Factory

Jens Hagerup started Den Norske Blyantfabrikk (The Norwegian Pencil Factory) in the spring of 1932. The company was founded on March 3, with Hagerup as CEO and sole board member, and registered in the Oslo Trade Register on March 12.

He brought in help from abroad to start production. On June 1 of the same year, the newspaper Nordlys reported that “A German specialist in the manufacture of pencils, George Scherf, has been granted a 6-month work permit at Den Norske Blyantfabrikk, Oslo, who will start pencil manufacture, a new Norwegian industry.”

During the summer of 1932, production began, and on September 10 of the same year, Helgelands Blad wrote:

The establishing of a Norwegian pencil factory has been successful, and Norwegian pencils are already on the market, the product has been registered for this year’s trade fair. They also hope to be able to prepare a Norwegian wood material that can be used for pencil production, and they intend to expand the business to also produce pen holders.

A couple of years after the factory had been established, they had seriously entered the market. Øvre Smaalenene reported in December 1933 that Norwegian pencils were beginning to gain ground in the school system. The Askim school board decided in a meeting on December 11 the same year that they would begin using pencils from Den Norske Blyantfabrikk. They had tested the pencils, and found that the quality was just as good as the better-known foreign pencils, and in addition far cheaper in price. One of the meeting participants “had previously complained about the Norwegian pencils, but now some new ones had arrived, and they were just as good as the foreign ones”.

Bidding dispute in Skien

Den Norske Blyantfabrikk was involved in a couple of strange conflicts in the mid-1930s. The first was a disagreement over a tender for pencils for the Skien school district in the autumn of 1935.

The school board had done a bidding competition for Norwegian pencils, which the merchant Erik St. Nilssen had won. The problem arose when the pencil factory, which was supposed to deliver the pencils to the merchant, found out that Nilssen had set a much lower selling price in his tender than what the factory had stated as a guiding price. The school board and merchant Nilssen believed that it had to be up to him to set the price he would sell the pencils at, while the factory believed that by setting such a low price he was undermining the market. They refused to deliver the pencils, which in turn, of course, made it impossible for Nilssen to deliver the order to the school board.

This led to a few rows back and forth, where the factory, the merchant and the school board took turns airing their dirty laundry in public, through the newspaper Telemark Arbeiderblad. the pencil factory wrote on October 9:

Den Norske Blyantfabrikk, like all other Norwegian industries, must have clean sales lines, from factory to wholesaler, from wholesaler to retailer and from retailer to consumer. So also with pencils for schools. And the prices must be stipulated with this in mind. When your bookstore offers pencils at prices that are below the prices a retailer must pay for the pencils, they are excluded from offering pencils to the schools. It is this situation that has been discussed, and we do not find it regrettable that the factory refuses to deliver the pencils to your bookstore when the case turned out as it did.

A few days later, the school inspector replied:

In this case, the school board is only dealing with bookseller Erik St. Nilssen, whose tender for the supply of pencils this year has been accepted by the school board. If a bookseller does not have the opportunity to set his own tender prices, the tender system becomes a caricature.

What happened next in this case – if anything – is not known.

Breach of contract with Industrihuset

Another peculiar case occurred in 1936, when Industrihuset A/S (translates to “The Industry House”) sued the pencil factory for breach of contract. Industrihuset was located in Trondheimsveien on Nedre Sinsen, and was one of the largest complexes of commercial buildings in Oslo. A large number of factories were located here, including Den Norske Blyantfabrikk.

The details of this case are a bit murky, but allegedly the factory had a contract which stipulated that Industrihuset had the right to exclusive sales of the pencil factory’s products. Industrihuset believed that the factory had prevented this. The pencil factory, for its part, believed that Industrihuset was also guilty of breach of contract, and ended up counter-suing. The case was first heard in the district court, which concluded that both parties were guilty. The two compensation amounts basically canceled each other out, with the result that the pencil factory had to pay a meagre intermediate payment of NOK 163,-. Industrihuset had to pay the legal costs of NOK 400,-.

Interestingly, both parties chose to appeal the case, and it eventually ended up in Supreme Court, which came to the same conclusion, but set a higher compensation amount. In addition, there were also higher court costs, which Industrihuset had to pay this time as well.

The two parties must have managed to come to some sort of agreement after this, because the pencil factory remained in Industrihuset.

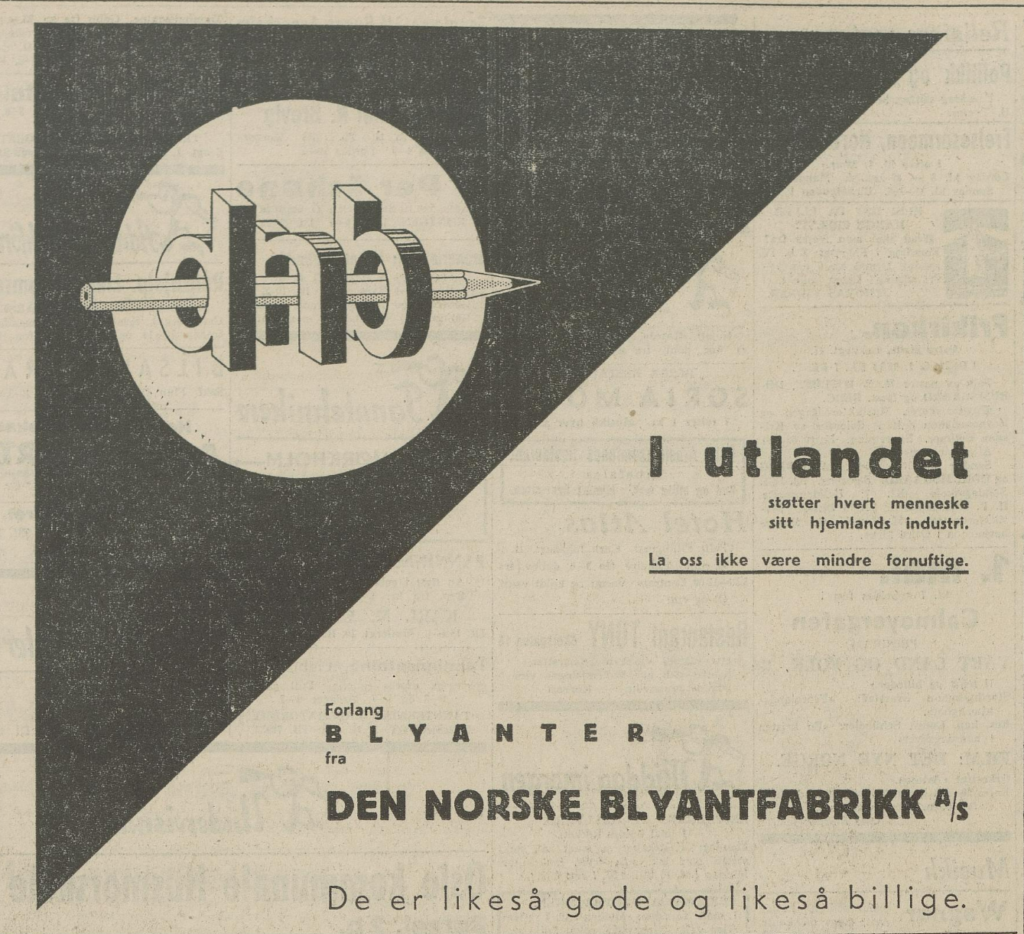

“Use Norwegian goods”

In 1937 Den Norske Blyantfabrikk had 12 employees, but Jens Hagerup stated in the journal Bygningsarbeideren that they could easily employ many more workers if Norwegian consumers stopped buying foreign pencils in favor of Norwegian ones.

The pencil factory launched a relatively large advertising campaign in the second half of the thirties where the main focus was to encourage consumers to buy Norwegian pencils:

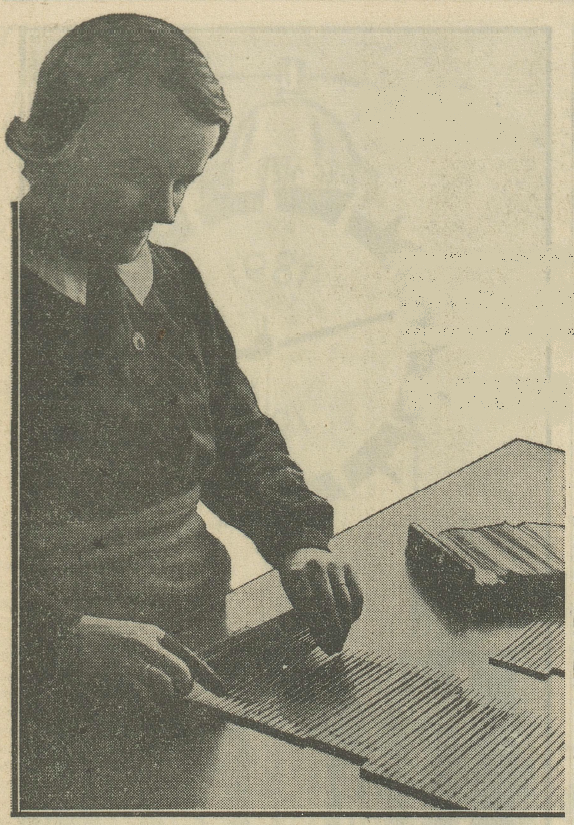

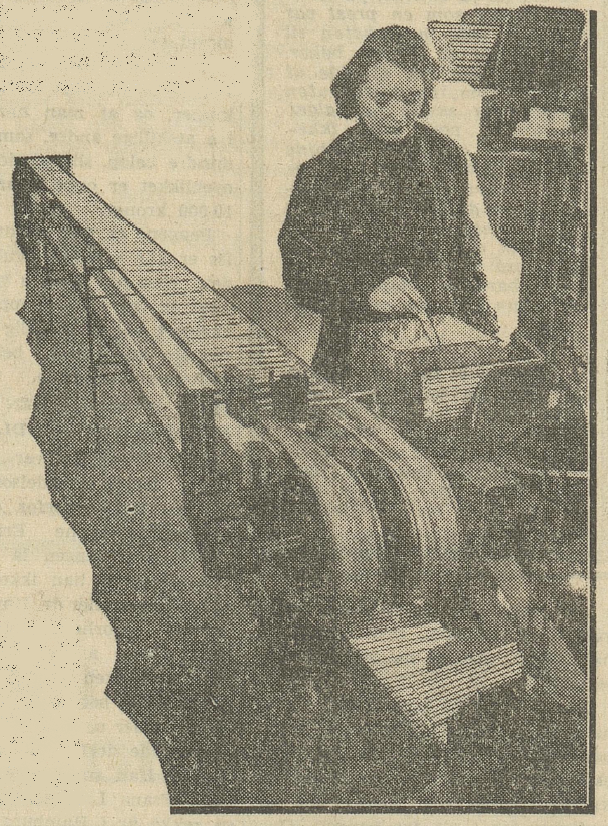

Tour of the factory

On March 7, 1941, the newspaper Dagbladet published an article about Den Norske Blyantfabrikk. They had visited the factory, and Jens Hagerup talked them through the entire production process:

We import both the leads and the wood that we use. The wood is cedar of different quality. It comes from California or the Southern States, cut into suitably long boards about the length of the pencil. The width can vary from three to about eight centimetres, and the thickness is slightly larger than half the cross-section of a pencil.

These small boards first go through what we call the groove machine, which planes one side smooth at the same time as it cuts out a series of parallel recesses, grooves, corresponding to half the cross-section of the leads. After the wooden boards have been coated with glue, the leads are inserted and then another board is glued over it.

The glued boards with the leads inside are placed under pressure. The next day, the boards get exactly the length that the pencil should have by being inserted into the scrubbing machine and from it they go into the planer. The planer is like the base, you see; because that is where the pencils come into the world. The planer tooth has the shape of a rotating wheel and by passing it on the upper side, the wooden board gets grooves corresponding to the number of pencils that can be made from a board, in this case eight. On the way back through the machine, the board now passes the underside of the razor teeth and the eight pencils fall brown and slender into the box.

From the planer it goes to the polishing machine, where six emery discs polish each side of the pencil, and then the coloring machine takes over. These pencils that you see here turn white; but we have all possible colors. Several layers of coloring are necessary, and then varnishing follows. After the pencil tips are polished to get rid of the paint that sticks to them after passing through the coloring machine, the pencils go to the stamping machine to get the company mark. Then they are bundled together, packed and ready to be sent to market.

Hagerup was then asked what wood they had in stock, as the import of wood from the US was non-existent in German-occupied Norway in 1941. The factory owner then explained that they had wood in stock, but that they could also make pencils from Norwegian types of wood, such as maple, aspen and white birch, although the American cedar was the best, as it had no knots. Cedar wood was also the easiest to sharpen.

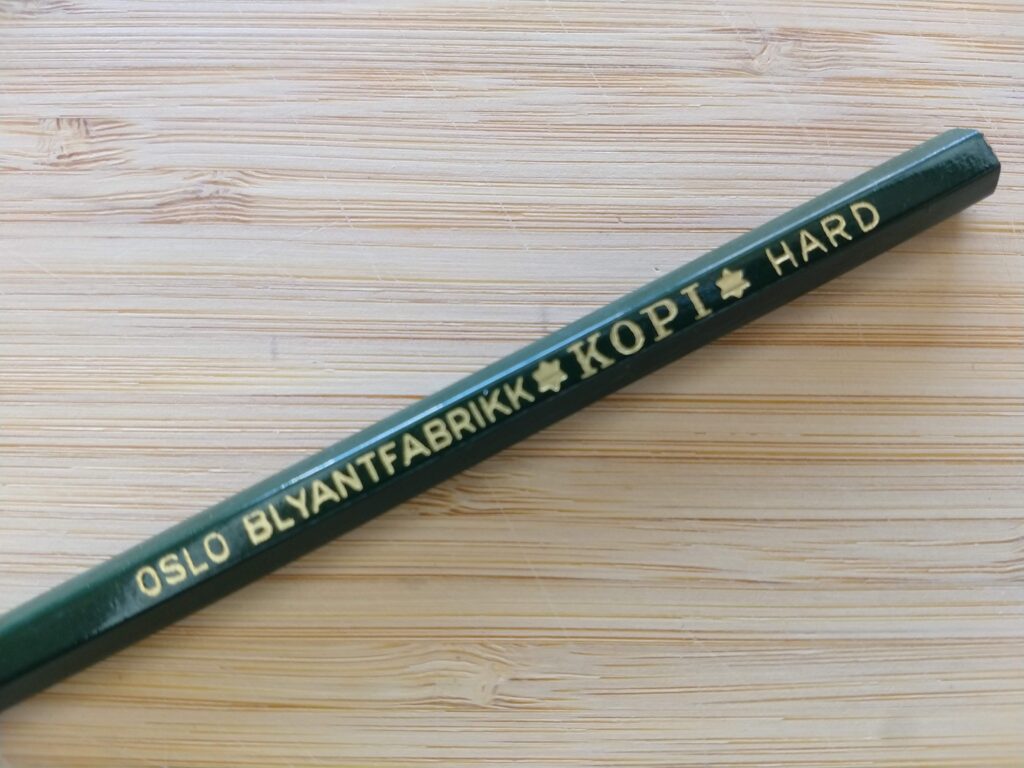

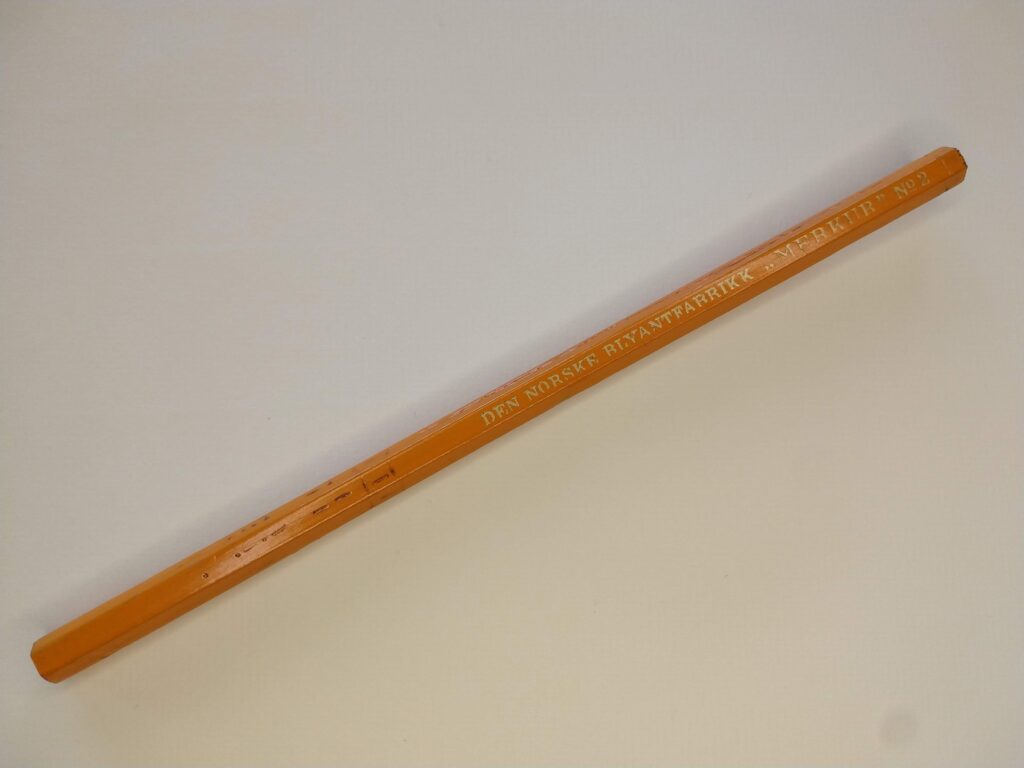

Hagerup mentioned in this interview that the Norwegian consumption of pencils was around 23,000 pencils per day. About half of this need was met by his factory and “the other Norwegian pencil factory in this country, Oslo Blyantfabrikk” (we will return to Oslo Blyantfabrikk (Oslo Pencil Factory) later in this post). Den Norske Blyantfabrikk had 8-9 workers at this time, who produced up to 14,000 pencils every day.

National Gathering, and exclusion from the authors’ association

Jens Hagerup was a member of the National Gathering (Nasjonal Samling, or NS) political party before and during the war. This was the Norwegian far-right nationalist party, led by Vidkun Quisling, who collaborated with the Germans during the occupation in 1940-1945. To a certain extent, you can see from Jens Hagerup’s novels and partly also statements he made, as well as some of the advertisements for his pencils, that he had a nationalist mindset. As a factory owner in an industry with strong competition from foreign companies, he obviously also had financial interests that may help explain this party affiliation.

The fact that Hagerup belonged to a group of authors who supported the Nazis during the war actually meant that his writing received a small boost in the media during the war years. After the war, however, these authors had a fall from grace. Those who had been on the side of the Nazis during the war were not highly regarded in Norwegian society in the post-war years, and experienced a good deal of criticism and exclusion. The Norwegian Authors’ Association had a meeting on October 1, 1945, where they decided to expel a number of writers from the association because they had been members of NS during the war. Jens Hagerup was one of these.

Hagerup had not written any books for several years at this point. His last book, “Sommernatt i Nordland” (Summer night in Nordland) had been published in 1934, and it would seem that he gave up his writing career at about the same time that he entered industry and became a factory owner. Nevertheless: his membership in NS probably shaped his legacy as a writer. For example, none of his books have been republished ever since, despite the fact that they were uniformly well received by reviewers when they were first published. Today, you can’t find anything about Jens Hagerup in any of the big Norwegian encyclopedias, or, for that matter, Wikipedia. Litteraturnett Nord-Norge has an entry on him, but what little information they have about him is inaccurate and contains several factual errors. For an author who actually published six novels, which were mostly talked about in positive terms by reviewers when they came out, it is strange that it should be so difficult to find information about him. But that was probably the punishment that both Hagerup and a large number of other writers and artists had to endure for choosing the wrong side during the war.

Without in any way defending those who supported the Nazis during the war, one can imagine that it must have been very strange and sad for people like Jens Hagerup, who was probably primarily concerned with preserving and strengthening Norwegian culture and industry, to be labeled traitors after the war. It is easy to judge in retrospect, but difficult for us today, eighty years later, to understand how people perceived and interpreted the chaotic situation the country was in during the war years.

Tax fraud

In 1947, Hagerup’s name was again in the media in a less than flattering context. The municipality of Oslo had grown tired of extensive tax evasion, and decided to publish a list of people who had been caught cheating on turnover tax. Jens Hagerup appeared on this list. He had to pay double tax for a period after it was discovered that he had paid too little over several years.

The newspaper Friheten wrote about the published list on January 7, 1947:

The decision [to publish this list] must be greeted with joy and will undoubtedly make those who feel tempted to prey on their fellow citizens think more than once before engaging in tax evasion.

It’s easy to draw a parallel here to some of the accusations against Hagerup in connection with the shop fire in 1922. He was not convicted at the time, but that does not necessarily mean that he was innocent. The fish theft in 1909 also comes to mind. The Nordlys newspaper did not want its readers to forget the fire, at least, and wrote on January 14, 1947:

The author Jens Hagerup (Nicolaisen), who is now stated to be a factory manager, is seen among the names of the tax evaders in Oslo. As is well known, he stood before the court some time ago, charged with arson and insurance fraud in Harstad.

Oslo Pencil Factory

Let’s put Jens Hagerup on hold for a little bit. What about his little brother, Aksel? We must not forget about him! Aksel followed in his older brother’s footsteps in many ways. He was nine years younger than Jens, and chose the same career path; Aksel also worked as a teacher for several years, and when Jens moved to Oslo, Aksel followed suit. In November 1933 he started his own company, and called it Norsk Papir og Blyantutsalg A/S (Norwegian Paper and Pencil Trading). The company was to sell pencils and paper products, and Aksel (who had now taken the surname Senjen, after the island he came from), was the sole board member. It’s possible that there was a collaboration between Aksel’s company and Den Norske Blyantfabrikk. It would be natural that Aksel worked to distribute the pencils that his brother’s factory produced, although this is only speculation, and is not confirmed in any of the sources I have found.

However: in the late autumn of 1936, this company changed its name to Oslo Blyantfabrikk A/S (Oslo Pencil Factory). What had previously been a wholesale company now stated in the Oslo Trade Register that they intended to start manufacturing pencils. This had to mean that Aksel was now in direct competition with his brother.

Source criticism

Among those who have taken an interest in these two pencil factories in recent years, there has been a general opinion that there was only one pencil factory, which operated under different names, or that Den Norske Blyantfabrikk at one point changed its name to Oslo Blyantfabrikk.

Wikipedia, Industrimuseum and Digitalt Museum all have entries about Den Norske Blyantfabrikk, in addition to the fact that the factory is mentioned in Litteraturnett Nord-Norge’s very brief article about Jens Hagerup, but all state that Jens and Aksel started the factory together and that this actually was the only Norwegian pencil factory that ever existed. I believe this is wrong, and that this misconception can be traced back to an article in the journal Bibliotekaren (No. 4, 1997). The article was written by two students in documentation science, who had a research project involving the private archive of Jens Hagerup. The article contains a three paragraph summary of Hagerup’s life and work, and here we find, among other things, the following:

In 1932 he and his brother, Aksel Senjen, founded Den Norske Blyantfabrikk A/S, the only one in Norwegian history.

The websites I linked to above all cite this article as a source in their listings about Den Norske Blyantfabrikk. Considering that the article was published in a trade journal, it would easily be regarded as a reliable source. When it says that Den Norske Blyantfabrikk was the country’s only one throughout the ages, and that Jens and Aksel started it together, and you later find other sources that mention that Aksel was the manager of Oslo Blyantfabrikk, you can quickly conclude that this was the same factory. If you go a little deeper, however, and look up a few more sources from Jens’ and Aksel’s day, it becomes quite obvious that this was not the case.

In my work on this article, I have accumulated an extensive collection of newspaper clippings, articles, advertisements and other documents about the two brothers and their pencil factories (see complete source list at the bottom of this article), but I have not found a single source from their contemporary time that suggests this was only one factory. They are consistently stated as two separate companies, they had two different addresses (Den Norske Blyantfabrikk in Trondhjemsveien 139 and Oslo Blyantfabrikk in Karl XIIs gate 7), they were founded at two different times, and ceased operations at different times.

The statement from Jens Hagerup in the interview in Dagbladet in 1941 where he refers to Oslo Blyantfabrikk as “the second pencil factory in the country” should really be good enough reason alone to put this discussion to rest once and for all.

The relationship between the two brothers

One might wonder why on earth Aksel Emil Senjen chose to start up a factory in exactly the same industry as his older brother, even in the same city! Was there a rift between the two brothers that prompted Aksel to start a competing business? Were they not friends, or was it just an extreme case of two brothers trying to one-up each other (“I have a better pencil factory than you!”)? Was it Aksel who looked up to, and “imitated” his older brother? Or was it an actual collaboration between the two factories? These are questions I have tried to find answers to while working on this article, but unfortunately I have not been able to get to the bottom of them properly.

The private archive after Jens Hagerup could perhaps give us some answers. This archive is located at the State Archives in Tromsø, but according to the Norwegian National Archives, it is “currently unorganized and therefore not available for use”. The archive is also blocked due to physical condition. I tried to contact the State Archives to find out if it was possible to gain access, but my request was refused due to the poor condition of the files. Thus, perhaps the most interesting questions surrounding these two factories, remains a mystery for the time being.

Duty increase

The only thing I have found that suggests any form of cooperation between them, was that the two pencil factories sent a few joint letters to the Directorate of Industry in 1953 and 1955 asking that the customs duties on pencils be raised. Both factories had experienced a decline in sales throughout the first half of the fifties. Both had also invested a lot of money in new equipment which enabled them to manage with fewer employees. In a letter to the directorate in 1953, it was stated that the two factories had a total of 24 employees, while in 1955 this number must have been considerably lower.

The factories hoped that a higher import tariff would encourage people to buy Norwegian pencils instead of foreign ones. This was eventually agreed to, and the customs duty was increased, but after Norway joined EFTA (the European Free Trade Association) in 1961, pencils could be imported duty-free from other EFTA countries. In the following years, more and more of the European countries joined, and this created a competition where the Norwegian pencil factories were unable to assert themselves. The Directorate of Industry tried to increase the customs duty for pencils further in 1963, without it helping significantly.

Liv Hagerup – The Industry Association’s only woman

Jens Hagerup’s daughter, Liv, was initially a ballet dancer, but when she turned 30 she retrained as a classical singer. She sang her debut concert in 1947, to a very lukewarm reception from the concert reviewers:

First of all, there was a lot of out-of-tune singing. The pitch was too sharp and uncovered, and poor support made the tone wobbly and uneven at the end of the phrases. The vowels didn’t get pretty treatment either. The singer somehow didn’t have a pedal that made the tone beautiful and singing. She cut off the melody line, and that resulted in a blunt and limp performance.

The merciless reviewer in the newspaper Friheten on December 8, 1947, then ended his review by applauding the accompanist for his brilliant musicianship, that he wished the singer also would have possessed.

Critisism like that could discourage the most hardened performer, but Liv traveled to Milan and took lessons with a famous opera singer there for a few years before returning to Norway. After that, she had moderate success as a singer throughout most of the fifties, although she admittedly never became a new Kirsten Flagstad. She also starred in a couple of films, first a small role in “The Song of Life“ in 1943. Ten years later, she had one of the main roles in the film “Selkvinnen“.

Taking over as president of her father’s pencil factory was probably the furthest thing from Liv’s thoughts, until she suddenly inherited this role when he retired from the company in 1960. Liv and her brother Robert had often helped with various tasks in the factory, so they knew the operation well, and Jens probably also wanted the factory to stay within the family. Liv stated in an interview in VG on May 9, 1962:

My brother is responsible for the management of the technical department. After all, we have several expensive, fully automatic machines that need to be looked after, and when our father retired in the early 1960s, Robert would much rather do that than look after the business management. I, on the other hand, enjoy taking care of money, so it came naturally that I became CEO.

By virtue of her position as president of the pencil factory, she was also the only female member of the Norwegian Association of Industry. Among those present at the association’s annual meeting and general assembly in 1962, there were 400 men, and Liv Hagerup.

At this time, most of the production at Den Norske Blyantfabrikk was automated. The factory had around 30 machines responsible for the production of pencils, and managed with just six employees, including the management.

Unfortunately, Jens Hagerup did not get a long retirement after he left his pencil factory to the next generation. He passed away on October 2, 1961, aged 77.

Robert Hagerup, and how pencil leads are made

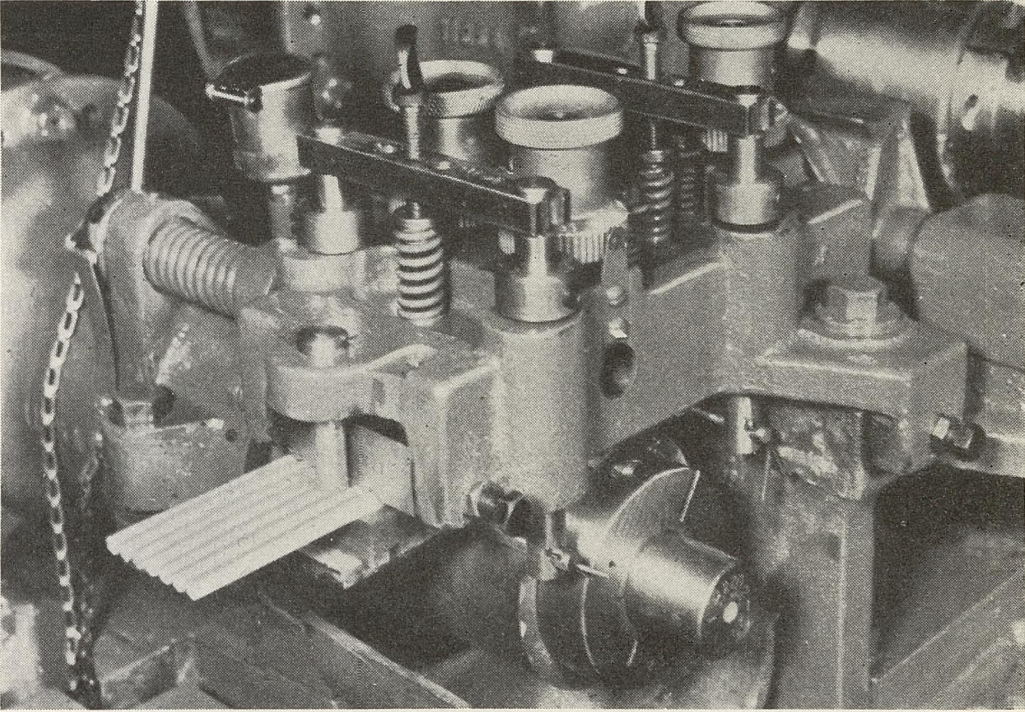

Robert Hagerup took over as CEO of Den Norske Blyantfabrikk in 1966. On December 20 the following year, the newspaper Arbeiderbladet visited the factory. At one point after the war, the pencil factory had started making the graphite leads themselves, instead of importing them from abroad as Jens Hagerup had said they did in 1941. Robert explained in detail how the pencil leads came to be:

The graphite, which comes from Ceylon, is what leaves the color on the page. The clay comes from Czechoslovakia and acts as a binding agent, while also regulating the degree of hardness. The clay must first be precisely cleaned and then ends up together with specific quantities of graphite in so-called ball mills – rotating iron drums filled with steel balls – where the material is ground well together before it goes into large grinders to be ground uniformly and finely, which can take several weeks. In filter presses, most of the water is then separated, and the substance that will eventually become pencil leads now resembles large and flat black cakes, which are dried in special drying cabinets.

After drying, a complicated treatment follows in kneading and rolling machines, where the mass is pressed out into something resembling black paper. We are now at the point where the leads can begin to be shaped, which takes place in a large steel cylinder, where there is a hole in the bottom exactly the size of the lead’s thickness. The hole is lined with precious stone, and through this the graphite paste is pressed with the help of a powerful piston. The mass comes out as a long line. Just outside the hole sits a rotating “steel wing”, equipped with an extremely sharp knife, which with a frequence of 300 times per minute cuts the string and removes the piece that has been cut off. The string is still soft and pliable, but after one more treatment, it should become a good and usable pencil lead.

The soft leads are placed under pressure and straightened, further dried and placed in refractory capsules in ovens with heat of around 1200 degrees [centigrade]. After a few hours, the leads are taken out (they are now sufficiently hard) and dipped in a mixture of melted grease and wax, which will ensure that the writing adheres to the paper as best as possible.

Hagerup indicated that in 1967 Norway had a pencil consumption of between 11-14 million pencils per year, and that his factory accounted for approximately 15% of these pencils. That would mean that Den Norske Blyantfabrikk in 1967 produced somewhere between 1.6 and 2 million pencils a year.

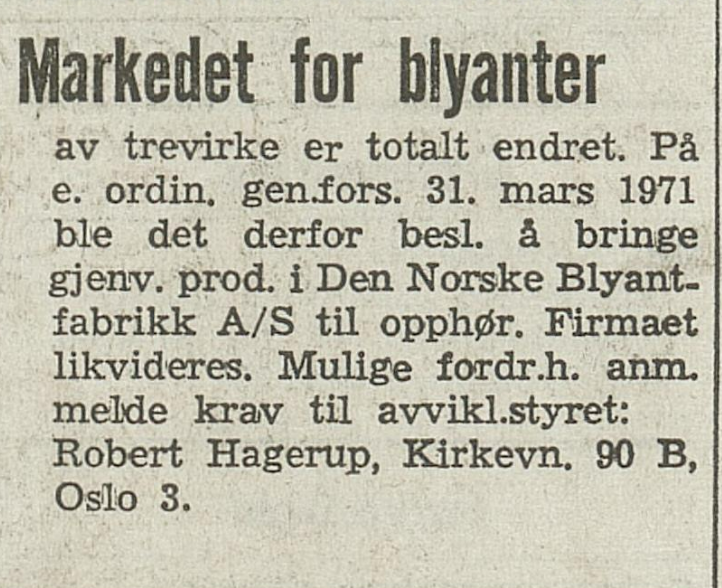

This was still not enough to keep operations going for very long. On April 6, 1971, after several years of struggle, there was a notice in Arbeiderbladet:

The market for wooden pencils has completely changed. On an extra-ordinary general assembly on March 31, 1971, it was therefore decided to halt production at Den Norske Blyantfabrikk A/S. The company is liquidated.

Fredrik Wassvik and the redevelopment of Vaterland

Aksel Senjen was CEO of Oslo Blyantfabrikk until 1967. Then his son, Fredrik Wassvik, took over the reins of this factory. Unfortunately, he had big difficulties keeping the family business going. The factory had only four employees at this time, and was struggling to keep the wheels turning. Fountain pens had made their way into schools, and ballpoint pens had been seriously adopted in society at large. The market for pencils was smaller than it had been a few years earlier, in addition to the fact that Oslo Blyantfabrikk had to compete against a large number of foreign brands that could mass produce to a greater extent and force prices down.

It’s safe to say that things were looking bleak, but what really put the nail in the coffin for Oslo Blyantfabrikk was the redevelopment of the Vaterland district in Oslo around 1970. The pencil factory was located at Karl den XIIs gate 7 in Vaterland (this street ran where Oslo City and Oslo Spektrum are now located, parallel to Stenersgata). In the 1960s, the news came that the area that made up Vaterland were to be demolished to make room for the subway’s joint section between Tøyen and Jernbanetorget. This work went on for a number of years, and led to major conflicts between those who lived in the area and the municipality, which was responsible for the demolition work.

In December of 1965, an agreement was signed in which the municipality took the responsibility of finding replacement premises for the companies affected by the clean-up. In the late autumn of 1972, Oslo Blyantfabrikk had not been relocated yet. At the same time, the buildings around them were demolished, water and electricity were disconnected, and building remains, dust and waste were strewn everywhere.

A clearly upset Fredrik Wassvik was interviewed about this in Aftenposten on December 23, 1972:

Ever since July, I have been promised replacement premises. Once I was offered premises in an old barn in Klemetsrud, another time in a house threatened with demolition at Kampen. I heard from the Housing Manager’s office that in the latter case I was guaranteed premises for the rest of my life. When I came to look at the building, I learned that it was soon to be demolished. The public officials who have been responsible for my case have clearly not had a good enough overview or insight to find a solution. I have the impression that my case has been languishing in public offices for months without processing. And I have to pay for this senseless system with my livelihood!

The building where the pencil factory was located was partially demolished at this time, although there were still a couple of businesses located there. All the doors of the factory had been broken, so that anyone could get in. Rain had also entered his storage rooms, causing NOK 60,000,- worth of water damage. The power went out, and the elevator stopped working. Without a lift, the factory had no way of getting the machines out safely, before they were destroyed.

Wassvik went on to say:

I was told over the phone that all my machinery would be destroyed with the demolition if I didn’t get it out soon. But how can I manage that, when they have already cut the electricity. I was able to salvage a few engines in the evening. I had to fumble my way in the pitch black with a flashlight to help! After the elevator was shut down, the open wall on the third floor is the only way out for the machines.

Nor have I got a cent back of the NOK 60,000 in values I lost due to water damage during the demolition work in the house next door. If I did, I might have had a chance to start up pencil production again. My own insurance company believed that this matter did not concern them. I had to make an inquiry to Oslo municipality, at the housing manager’s office, they said. But their legal secretary, Gunnar Kjendlie, stated that this was a matter I had to sort out with my insurance company or with the demolition contractor.

The factory never got back on its feet after this. The company existed on paper until it was decided to cease in August of 1975, but by that time, they had not produced pencils since the autumn of 1972.

Aksel Emil Senjen became an old man. He passed away in 1987, aged 94. His son, Fredrik, died in 2007.

Conclusion

Of the two brothers Jens and Aksel, it was clearly Jens who got the most attention in the media. As an author, he was more of a public figure, and although his books were almost forgotten after the war, he probably benefited from the fact that people knew who he was, even later in life. His daughter, Liv, was also in the public eye, as she was a singer and actress. Aksel and his son Fredrik were more anonymous in the media, and therefore it is also more difficult to find detailed information about them.

The work on this article started with a few advertisements for Den Norske Blyantfabrikk, but grew out of all proportions as I began to dig into the research, and found out more and more about the people behind the factories. In the end, I ended up with an incredible list of over sixty separate sources. I’ve included the list below here, with links (though all sources are in Norwegian, and I suspect that a lot of them can only be accessed from a Norwegian IP-address). I have put a lot of effort into making sure that the readers of this article can trust it to be reliable. It has been very important for me to be able to back up each and every claim with good sources (preferably also confirmed several places), especially because there is already some misinformation about these two factories out there. It was important for me to clear up the existing misconceptions, and I feel confident that I have succeeded in that through this article.

At the beginning of the 1950s, when the pencil factories were at their height, 7,200,000 pencils were produced in Norway each year. There may have been a few smaller factories in the country that also made pencils at the same time, but it is probably safe to assume that the vast majority of these pencils were made at the two Oslo factories. Both factories were very successful for many years, and both managed to pass on to the next generation before going under. Who would have thought that a couple of fish thieves from Tranøy would be able to pull off something like that?

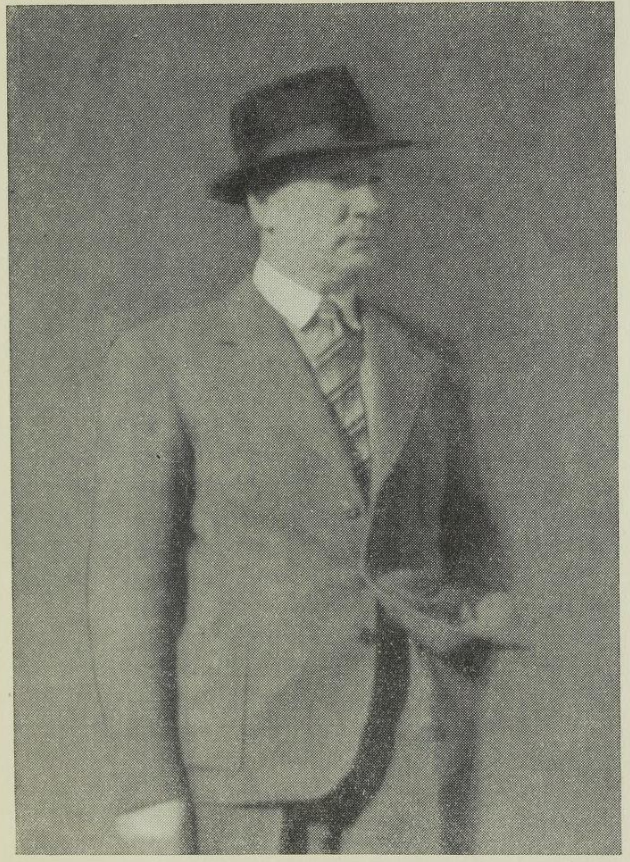

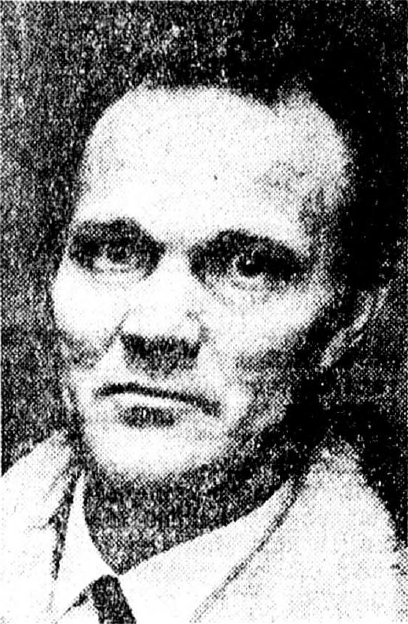

Cover photo: Jens Hagerup and Aksel Senjen. The photographers are unknown.

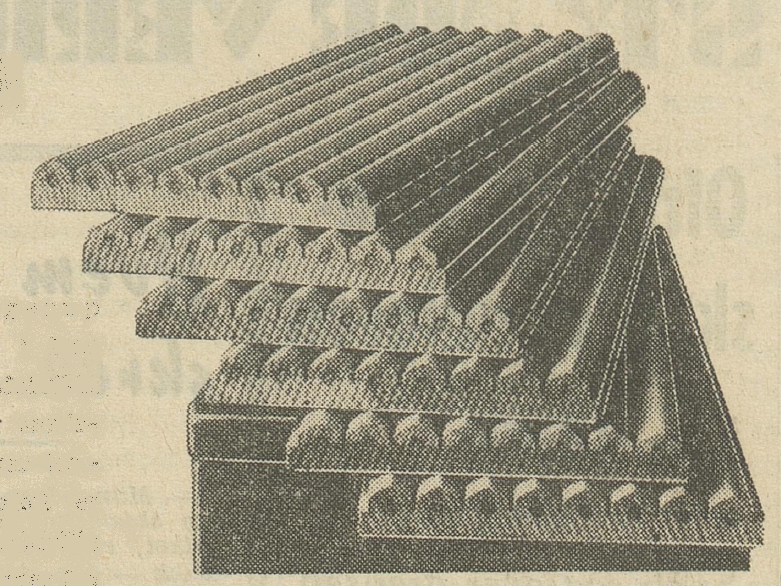

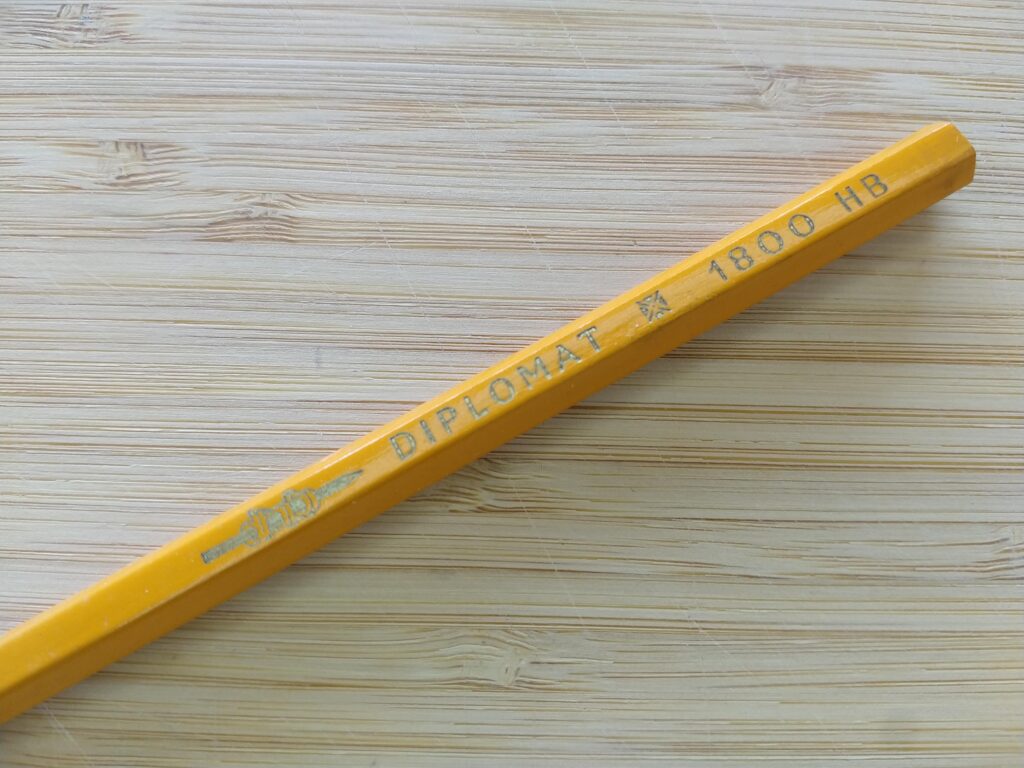

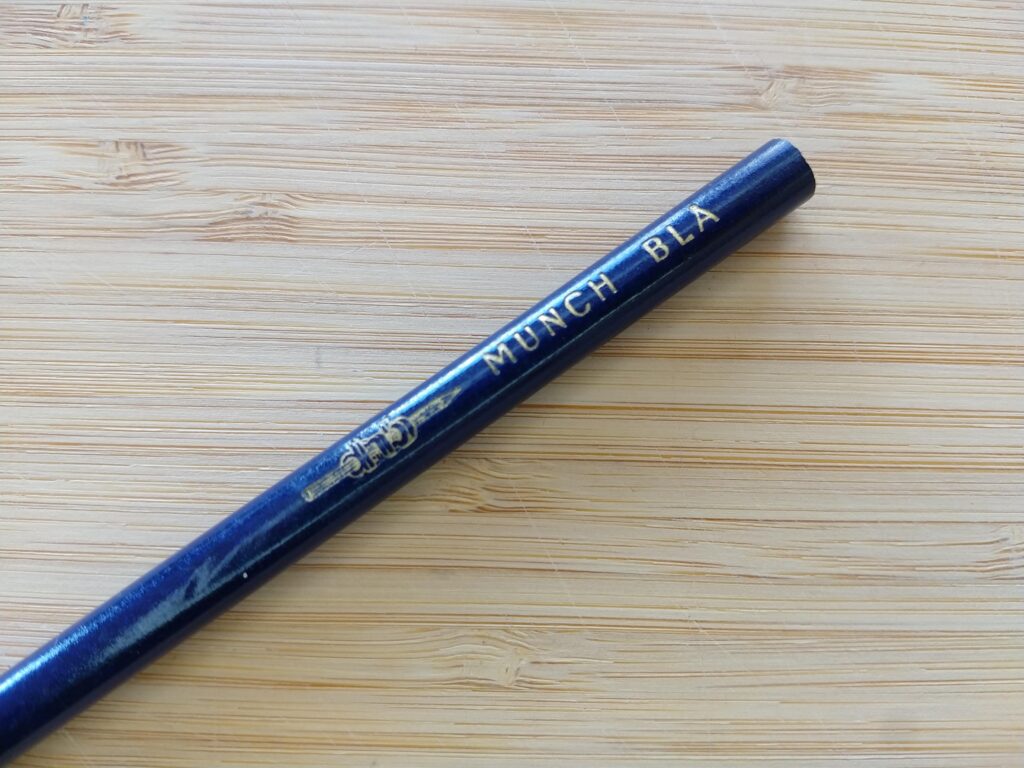

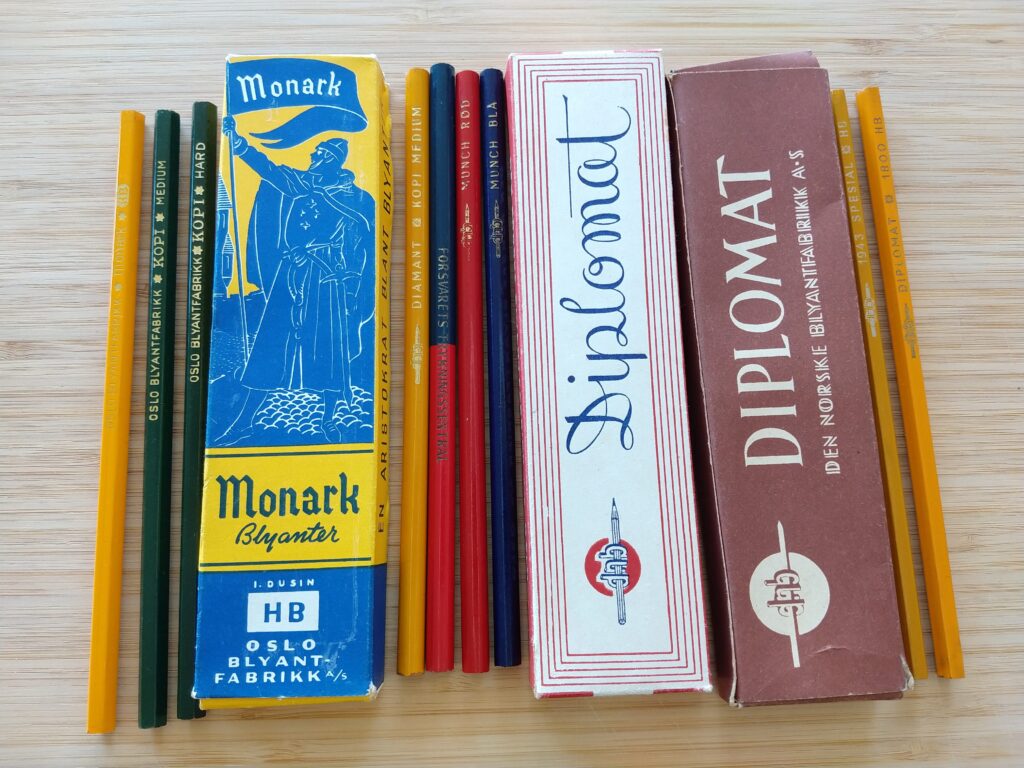

Big thanks to Kjartan Skogly Kversøy for pictures of pencils and boxes from his collection.

Jens Hagerup’s novels are all available online at the Norwegian National Library:

– Susanna (1922)

– Adam Børingen (1924)

– Brenning (1926)

– Maria (1927)

– Juvi (1928)

– Sommernatt i Nordland (1934)

Sources

– Wikipedia

– Digitalt Museum

– Industrimuseum

– Bodø Tidende, 17.10.1911 – «Lagmandstinget»

– Helgelands Blad, 24.10.1911 – «Tyveri fra hjell»

– Norsk Kundgjørelsestidende, 28.08.1919 – «Hagerup Vassvik & Co.»

– Norsk Kundgjørelsestidende, 08.12.1921 – «J. Hagerup & Co. aktieselskap»

– Harstad Tidende, 03.12.1923 – «En assurancesvik-affære»

– Nordlys, 26.02.1924 – «Et omfattende synderegister»

– Harstad Tidende, 27.02.1924 – «Saken mot Jens Hagerup»

– Harstad Tidende, 29.02.1924 – «Saken mot Jens Hagerup»

– Harstad Tidende, 03.03.1924 – «Saken mot Jens Hagerup»

– Harstad Tidende, 05.03.1924 – «Brandsaken mot Jens Hagerup»

– Harstad Tidende, 07.03.1924 – «Brandsaken mot Jens Hagerup»

– Harstad Tidende, 10.03.1924 – «Brandsaken mot Jens Hagerup»

– Harstad Tidende, 12.03.1924 – «Brandsaken mot Jens Hagerup»

– Nordlands Avis, 14.01.1927 – «Levende modell»

– Øvre Smaalenene, 22.01.1932 – «Fabrikeres blyanter i Norge?»

– Nordlys, 01.06.1932 – «Norsk blyanter!»

– Helgelands Blad, 10.09.1932 – «Norske blyanter og penskaft»

– Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1932 – «A/S Den Norske Blyantfabrikk»

– Øvre Smaalenene, 12.12.1933 – «De norske blyanter vinner terreng»

– Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1933 – «Norsk Papir og Blyantutsalg A/S»

– Telemark Arbeiderblad, 21.09.1935 – «Merkelig optreden av Den norske blyantfabrikk»

– Telemark Arbeiderblad, 09.10.1935 – «Hvem skal bestemme prisen på blyantene?»

– Telemark Arbeiderblad, 14.10.1935 – «Den norske blyantfabrikken igjen»

– Bygningsarbeideren, 1937, vol. 15, nr. 11 – «Den nye industri»

– Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1937 – «Oslo Blyantfabrikk A/S»

– Dagbladet, 05.01.1938 – «Den Norske Blyantfabrikk begikk kontraktbrudd»

– Dagbladet, 07.03.1941 – «Hr. Blyanten forteller»

– Oplendingen, 26.11.1943 – «Nasjonalsosialister i norsk diktning»

– Nasjonalsosialister i norsk diktning, 1943

– Harstad Tidende, 12.04.1944 – «90 år»

– Telemark Arbeiderblad, 03.10.1945 – «Forfattere strøket av Forfatterforeningen»

– Friheten, 07.01.1947 – «Skattesnyterne i Oslo SKAL FRAM I LYSET»

– Arbeiderbladet, 08.01.1947 – «Skattesnyteri i Oslo»

– Nordlys, 14.01.1947 – «Forfatteren Jens Hagerup»

– Arbeiderbladet, 02.12.1947 – «Debut torsdag»

– Friheten, 08.12.1947 – «Sangdebut»

– Arbeiderbladet, 22.08.1950 – «Konsertsesongen tar form»

– Friheten, 01.09.1951 – «Sangkonsert»

– Arbeiderbladet, 03.11.1951 – «Industribygget på Nedre Sinsen»

– Norsk treindustriarbeiderforbund 50 år, 1951

– Stortingsforhandlinger, 1953, vol. 97, nr. 6all – «Tariff for innførselstollen og for tara.»

– Urd, 1953, vol. 57, nr. 22 – «Selkvinnen»

– Stortingsforhandlinger, 1955, vol. 99, nr. 1b – «Om tollavgifter – Blyanter, fyllepenner og penneholdere»

– Handelsregistere for Kongeriket Norge, 1956 – «A/S Den Norske Blyantfabrikk»

– Arbeiderbladet, 18.06.1957 – «25-årsjubileum i blyantfabrikken»

– Harstad Tidende, 23.09.1959 – «Senja-væring startet den første blyantfabrikk i Norge»

– Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1960 – «A/S Den Norske Blyantfabrikk»

– Aftenposten 05.10.1961 – Dødsannonse Jens Hagerup

– VG, 09.05.1962 – «Fra konsertpodiet til direktørstolen»

– Stortingsforhandlinger, 1963, vol. 108, nr. 1 – «Blyanter (unntatt mekaniske), blyantstifter, grifler…»

– Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1966 – «Den Norske Blyantfabrikk A/S»

– Oslo Adressebok, 1966, vol. 88, nr. 2 – «Blyantfabrikker»

– Arbeiderbladet, 20.12.1967 – «Viskevennlig skriveredskap litt av en blyant-genistrek»

– Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1968 – «Oslo Blyantfabrikk A/S»

– Arbeiderbladet, 06.04.1971 – «Markedet for blyanter»

– Arbeiderbladet, 20.04.1971 – «Filtstift og kulepenn vinner fram i skolen»

– Aftenposten, 23.12.1972 – «Vaterland-saneringen et mareritt for næringsdrivende som må ut»

– Arbeiderbladet, 30.09.1975 – «Kreditorinnkallelse»

– Aftenposten, 02.09.1987 – Dødsannonse Aksel Senjen

– Nordlys, 18.05.1996 – «Omstridt forfatter frem fra glemselen»

– Bibliotekaren, 1997, nr. 4 – «Jens Hagerup-prosjektet»

– Aftenposten, 04.05.2007 – Dødsannonse Fredrik Wassvik