Point to paper – Pencil Problems in Parliament

This post is about a forgotten pencil maker who contributed to unrest in the British Parliament one summer’s day in the late 1800s. You will get to know a pencil pioneer who went from running a one person craft business that developed into a successful industrial enterprise. Last but not least, you will receive a thorough introduction to how you can protect your tip.

Most tips remain unprotected even in 2024. It is time that this neglected task was addressed. One would think that this was an obvious case and that most people would know better. The realities are discouraging. This is despite the fact that tip protection is both readily available, uncomplicated and affordable. Owners of vulnerable tips have a responsibility to contribute to ensuring that they remain functionable. This is not a task you can expect others to do for you. We live in a time in history when tip protection is one of many forms of moderation and sustainability that is only becoming more and more important. The innovative pencil maker, who also created pencil panic in the British Parliament in 1891, was also a pioneer in this area. Together with his smart employees, he came up with good solutions for protecting delicate tips over one hundred years ago.

On Monday the 13th of July 1891, The Derby Daily Telegraph printed shocking news. It had been revealed that the British Post and Telegraph Department used German pencils. The case was presented with great seriousness from the lectern in the House of Commons. Dr. Charles Kearns Deane-Tanner was furious. How could it be that the British authorities used German pencils when the British themselves made some of the world’s best pencils? The matter was raised during the July sessions of the British Parliament in the summer of 1891.

Dr. Deane-Tanner pointed out that pencils from the manufacturer J.W. Guttknecht were to be found everywhere in the state apparatus. The company was clearly aware that they had infiltrated Parliament by undisguisedly supplying a pencil specially marked for the task. The pencil was called J.W. Guttknecht Bavaria Civil Service HB . Everyone had to understand that it was both provocative and suspicious to find pencils marked in this way abounding among the civil service. Imagine finding Bavarian (!) pencils in the hands of the power elite in the British capital.

Something had to be done. British newspapers naturally jumped at the opportunity. They had been given a hot case to play with during the summer holidays. It provided opportunities to air xenophobia, conspiracy theories and suspicions of corruption. Everything the media could want in a season when cucumber news tended to dominate. Do you think pencils are a strange thing to make so much noise about? There is something to learn here for those who want to be seen and heard. Small and concrete matters engage. In a neighboring country (Norway) in the month of July 132 years later (2023), sunglasses were a central ingredient in the big political summer scandal that year. The sunglasses storm did not subside until the party leader threw in the towel and said goodbye to his job.

When a matter as special as this was put on the agenda, it was no surprise that it was Dr. Deane-Tanner who did it. He used every opportunity to blow up issues he thought could be used to make himself more visible. He was famous for unearthing unconventional angles that were suited for making noise. Dr. Deane-Tanner often chose particular political strategies to gain the limelight. Among other things, he was known for being the politician who had been expelled the most times from the House of Commons for excessively violent speeches.

Whether Dr. Deane-Tanner was just creating unnecessary drama, or whether the matter was actually perceived as serious, is not clear from the newspaper articles I have seen, but it was not inconceivable that pencils in particular could be something that affected the British national feeling. In the early 19th century, 90 years earlier, British pencils had been among the high-tech products that had been banned from being exported to France. The graphite on which the pencils were based was at the time a rare and sought-after raw material. British pencils were considered critical war materiel during the Napoleonic Wars.

Quality graphite also gradually became central to many casting processes. One of them, for example, helped to improve the production of artillery ammunition. In 1856, the Morgan brothers established the Patent Plumbago Crucible Company in Battersea, London. The company exists to this day and is known as Morgan Advanced Materials . They helped revolutionize metal casting processes using British graphite. Another example of British graphite being a key part of the high-tech side of the war industry at the time. Indeed, graphite continues to be a mineral of high-tech relevance even in our time. You find it in everything from fast computers to efficient car batteries.

Napoleon was thus directly affected by the ban on the export of pencils. He was forced to find other solutions to get enough pencils for his war machinery. He took the challenge very seriously and chose to initiate his own development programme. In many ways, modern pencil production was born as a consequence of this development program. Nicolas-Jacques Comté was given the task of solving the problem. He was a French universal genius who not only found the solution, but who in that way also further developed the pencil. The only thing the British achieved with the export ban was to gain new capable competitors.

In the pencil’s infancy and until the end of the 19th century, pencils had most often consisted of a rough piece of raw graphite that was lightly processed after extraction from the mines in Borrowdale in England. The natural graphite was cut into slices and then into thin square rods. The staves were then wrapped in wood. The shape of the graphite sticks could are similar to those we find in wooden square carpenter pencils today. The pencils worked fine when the graphite cutting went well and the graphite was clean, but often the it was not clean and the cutting was not successful. This meant that you often couldn’t predict the quality of the individual pencil. You could find that your pencil consisted of several broken pieces of graphite that were simply put together and then wrapped in wood. Pencils were even sold on the black market. If you bought one in this way you might come home with a piece of wood that looked like a pencil but only contained a tiny tip of graphite. Of course, there were quality brands, but these pencils were expensive. The manufacturer B.S. Cohen had even found ways to compress graphite dust into uniform graphite rods, but it was still immature technology. It was still far away from the technology of producing modern pencils.

Comte, on the other hand, invented an elegant ceramic material which was based on graphite dust and which could produce graphite rods of predictable quality. The method he developed also allowed for a variety of hardnesses on the pencils. The background was that the French did not have access to graphite of such good quality that it could be used directly for pencil production. The graphite had to be ground to dust first and then cleaned of unwanted material. Comté invented a high-tech ceramic product made from purified graphite powder mixed with fine clay and secret binders. The mixture was shaped into round sticks and baked in an oven at high temperatures. The process is called the Comté process and is roughly the same as the one used to make pencils today. Nicolas-Jaques Comté used only eight days (!) to change the pencil industry forever.

The pencil was important. It enabled effective communication. Communication was one of Napoleon’s strategic strengths. Anyone who has ridden a horse understands that a fountain pen and ink are far from ideal writing implements for a rider. The pencil, on the other hand, could withstand rough handling. It worked in all conditions and was uncomplicated to use. The pencil would continue to be important in war for more than 150 years. In Britain, as late as World War II, it was actually a criminal offense to waste pencils. Pencils were rationed. They were considered an essential piece in the war machinery. For example, it was forbidden to use mechanical pencil sharpeners. They increased pencil consumption unnecessarily.

The pencil issue that came on the agenda in the summer of 1891 was not only about the use of foreign pencils. There was speculation as to whether there could also be corruption in the civil service. Several British pencil manufacturers, who had tried to compete for supplying office supplies and writing implements, claimed that they had received unopened samples in return from Parliament. I don’t know if there actually was any corruption in this case, but it was easy to make an enemy of a German pencil manufacturer anyway. Allegations of suspicious foreigners have always been effective to resort to. In any case, xenophobia was no less real in 1891.

It is important to note that J.W. Guttknecht made high quality pencils. The accusations of corruption could therefore just as well be about envy. The British were no longer alone in making good pencils. The Germans were far ahead when it came to the latest in innovative pencil production. I have no doubt that the efficient German factories of this time could probably easily compete on price and quality with the British suppliers. J.W. Guttknecht was at this time one of the largest pencil manufacturers in Bavaria.

Have you never heard of the pencil manufacturer J.W. Guttknecht ? Then I can tell you right away that you have serious gaps in your pencil knowledge. You are not alone. Unfortunately, I must also admit that I had not heard of this pencil manufacturer either just a few months ago. If you use pencils, I still expect that you have heard of Faber. This is today one of the world’s most famous pencil manufacturers. It is true that there have been several manufacturers with this name, but today they are all united under the name Faber-Castell. All the different Faber manufacturers had origins within the same family anyway.

Do you know who taught the first Faber to make pencils? Yes, it was precisely a Guttknecht. The history of the pencil manufacturer J.W. Guttknecht begins with Johann Andreas Guttknecht. He came from Frankfurt am Main and had been making pencils since at least 1750. There is evidence that pencils were produced in Stein in Frankfurt am Main as early as 1717. It is possible that this production had taken place even earlier than this. Kaspar Faber was Johan Andreas Guttknecht’s apprentice sometime between 1750 and 1761. Faber was training to become a carpenter and had been given the opportunity to learn how to make pencils from Guttknecht. He learned quickly and after a short time he started selling his own quality pencils. Guttknecht feared for his livelihood and tried to ban Faber from making his own pencils, but pencil production did not gain status as a separate profession until 1795. It was therefore free for anyone to produce and sell pencils. Faber established his own pencil company in 1761.

In 1790, his son Johan Lothar Guttknecht took over the production of pencils and converted the craft business into a factory. He became very rich and eventually built himself a magnificent villa in Mühlstrasse in Stein. The house is still standing. Guttknecht based his production on hydropower. Johann’s fourth child, Johann Wilhelm Guttknecht, then took over the business and changed the name to J.W. Guttknecht. 152 people worked at the company as early as 1874. At that time, there were 26 pencil manufacturers in Bavaria. J.W. Guttknecht was considered the third largest after A.W. Faber and J.J. Rehbach. The factory used both water power and steam engines. You can read more about the history of the company here . J.W. Guttknecht was eventually merged with Faber-Castell in 1907. Pencils were produced under the J.W. Guttknecht name until the late 1930s. The symbol with the scales printed on modern Faber-Castell pencils is a legacy from J.W. Guttknecht.

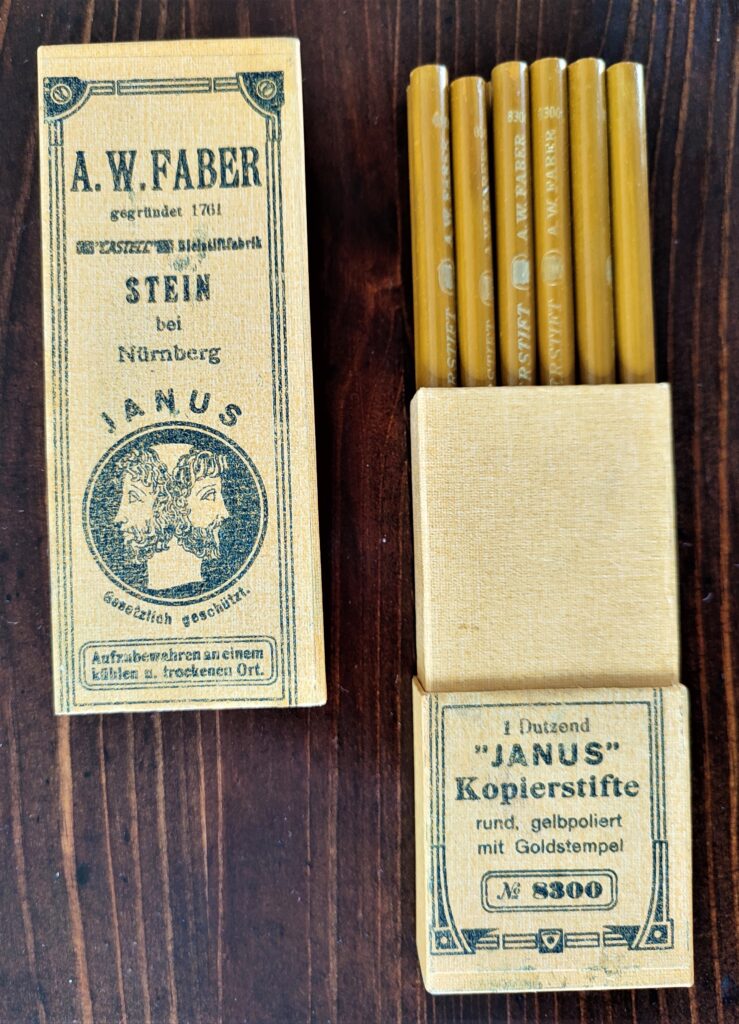

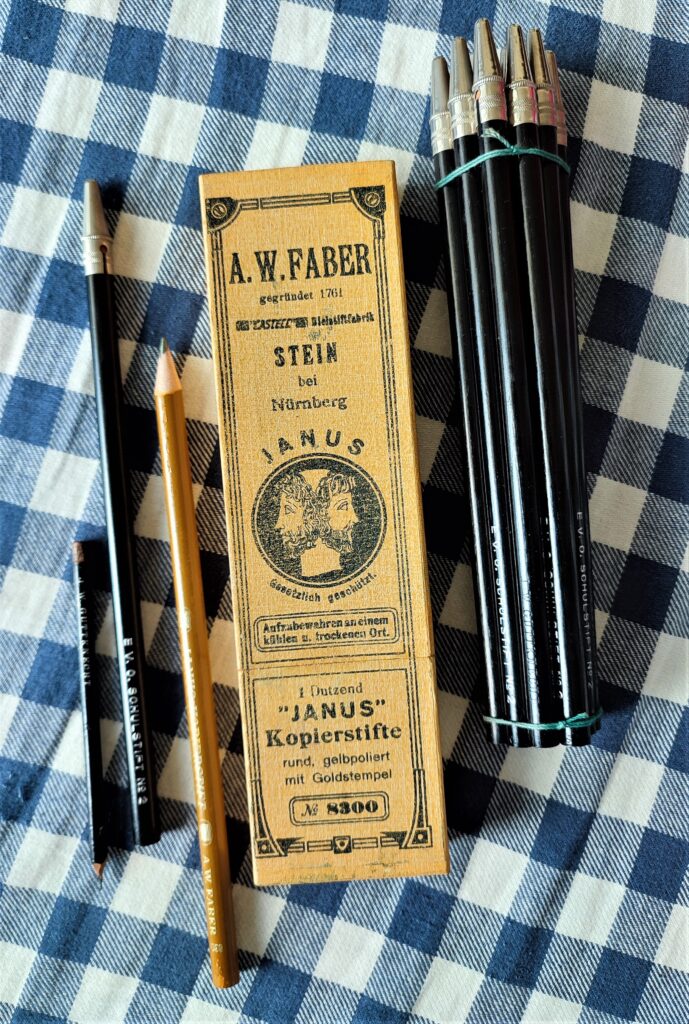

Guttknecht pencils are hard to come by today, but once upon a time they were one of Germany’s largest pencil manufacturers. I have been lucky enough to get my hands on original unused pencils from the manufacturer. They ooze quality. The school pencil, which I got hold of, was delivered with its own protection for the tip. It’s actually a bit strange that not all pencils come with a cap. The wood withstands beatings, but the graphite tip breaks easily.

The load tolerance for pencil tips has actually been researched. Here we are talking about how sharp a pencil should ideally be in relation to the load the tip itself can withstand. I have previously written an entire post specifically dedicated to this issue. Pencil sharpeners and possible variations in the tips themselves are also discussed. You can click on the link if you are curious: Do you want specialist expertise?

In 1979, Donald Cronquist published an article about the mysterious pencil tips in the American Journal of Physics . The article is called Broken-off Pencil Points . Cronquist writes the following about what triggered his research (Cronquist in Petroski 1989, p.245):

Some time ago I was clearing my desk top after completing an unusually long hand-written rough draft. I became mystified as I discovered a very large number of broken-off pencil points (BOPP’s) lying between and behind the books and other reference materials on my desk. The BOPP’s had apparently flown to these hiding places upon snapping off of my newly sharpened pencils. The mysterious thing about the collection of BOPP’s was that they were almost all nearly identical in size and shape.

I recommend anyone using quality pencils to get nib protectors. Then you can sharpen several pencils in advance and you will always have a sharpened pencil ready. It is not only about sustainability and moderation, but also about having a perfectly pointed writing instrument ready and protected. Few things are more annoying than pulling out a pencil with a broken tip. Here (JetPens) is a website that has a good selection of nib changers.

J.W. Guttknecht knew that a cap to protect vulnurable nib was important. Not least they were important for school pencils. School children are not known for being careful and Guttknecht wisely chose to remedy this by including a metal cap with every pencil. I don’t know how the pencil problems in the British Parliament ended, but if the case was they stopped using German pencils from J.W. Guttknecht, then it is just another reminder that cucumber news is not to be a trifled with.

References

Petroski, H. (1989). The Pencil. A History of Design and Circumstance. London • Boston: faber and faber

Rees, D. (2012). How to Sharpen Pencils. A practical and theoretical treatise on the artisanal craft of pencil sharpening, for writers, artists, contractors, flange turners, anglesmiths, and civil servants, with illustrations showing current practice. New York: Melville House

All photos in this post were taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy. The references are also, to some extent, included in the text in the form of links. They are easily recognizable in blue. Just click on these if you want to explore the topic further.