Nibby Sunday – Tolkien and the Fëanorian Letterforms

Yesterday, September 2nd, marked the fifty year anniversary since the death of my absolute favorite author, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. I thought this would be a good time to dedicate a blog post to Tolkien, and write a little about my own relationship with him and his stories. In the second half of this article, I will look more closely at Tengwar, which was a set of letterforms, a script he developed for his mythology.

My interest and fascination with Tolkien’s writings started when I was ten years old, in the mid-1990s. A friend I played with in the school band recommended me The Hobbit. Or – ordered me to read it – might be more correct to say. But it didn’t take much persuasion. I was already a book lover, and went straight to the library to borrow a copy. It took me three weeks to read it. I don’t know why I remember exactly that, but it just stuck in my memory: the copy I read was 309 pages long and took me three weeks to read. It was probably one of the larger books I had read at the time, and I also remember that the language seemed a bit old-fashioned and difficult to read (no wonder; the book was already almost sixty years old at this point). But the world, the different peoples, and the story itself made an indelible impression on me. Dwarves, hobbits, elves, goblins and trolls, great eagles and a man who could turn into a huge bear, a wizard, giant spiders who could talk. Not to forget: Gollum, and the ring that could make the wearer invisible! The 309 pages were jam-packed with adventure!

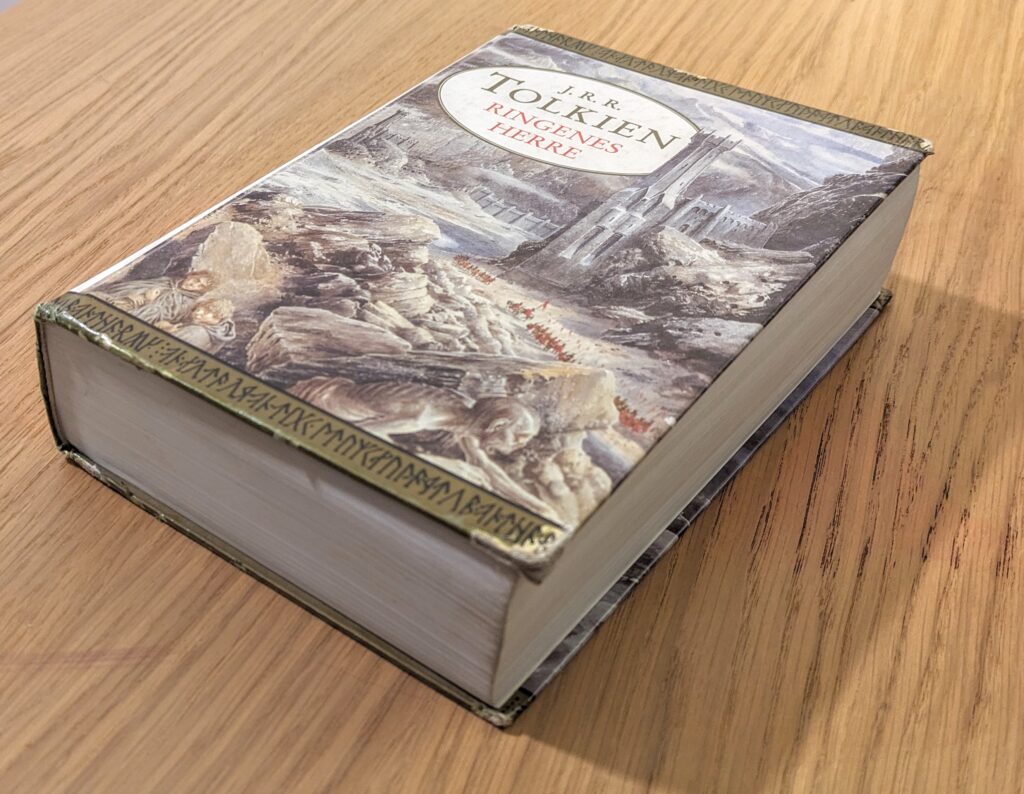

By the time I had finished reading The Hobbit, the guy who recommended it to me (and who was only a year older than me) had managed to plow through the entirety of The Lord of the Rings. He was a more prolific reader than me, but I couldn’t be any worse, so I threw myself into that as well. The first read-through took me about a year (I read it in stages, and had quite a few breaks along the way). The well over thousand pages were hard to get through for a ten-eleven-year-old, but at the same time the story was so good and engrossing that I just had to read on. There were probably many details that I missed in this first reading, but I worked my way through it, slowly but surely. Since then, Tolkien has always been a part of my life in one way or another.

In middle school, a class mate of mine was reading The Lord of the Rings for the first time, and I decided that I should read it again, to brush it up, and be able to discuss it with him. For a long period, we carried this huge tome in our rucksacks to school every single day, and regularly sat and leafed through it, read excerpts, studied the family trees in the appendices at the back of the book, and tried to learn the two written languages that were also explained in the appendices. We eventually became fluent enough to write secret notes in Tengwar to each other in class.

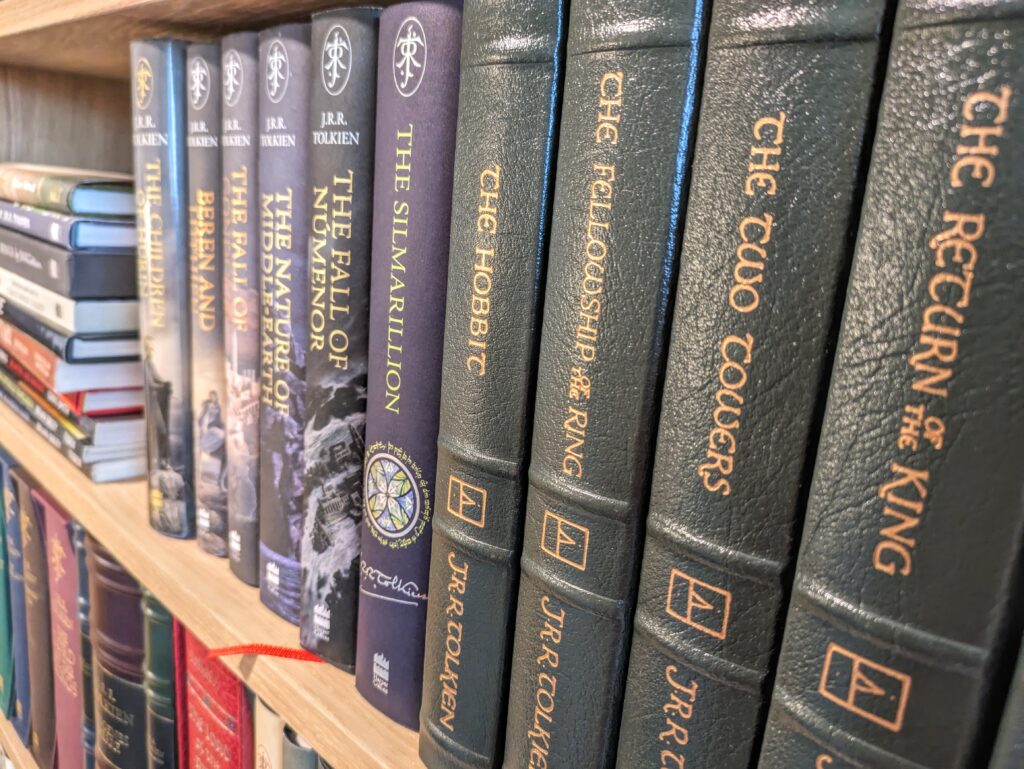

Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies came out before Christmas the three years I was in high school. Every single year the film premiere coincided with my school’s Christmas proms. It was a no-brainer. I didn’t attend a single Christmas prom during my high school years. The films made me dive even more into Tolkien’s world. I read The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit several times during the second half of my teenage years, and books like The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales, which take the reader even deeper into the subject matter, were also voraciously digested.

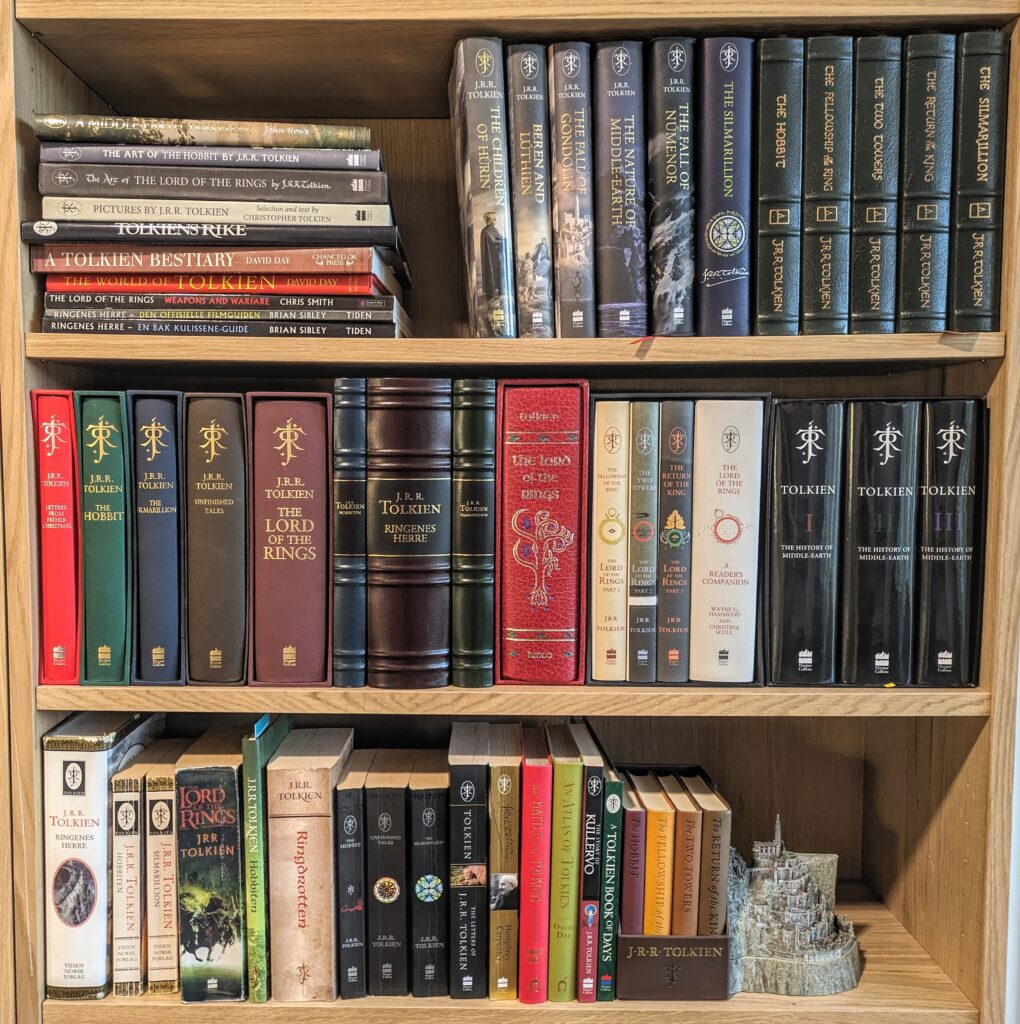

Towards the end of my university studies, I got the idea to buy a new edition of The Lord of the Rings as a Christmas present for myself every year. This was a tradition I kept going for a while, and it led to a small collection of some beautiful versions of these books: some illustrated, some with different forewords or other content that the others didn’t have. Some just because they were nice. I haven’t kept up this tradition, but in recent years I’ve periodically ended up buying Tolkien books, including books I already own, if I find them in an exciting edition that adds something new to my little Tolkien collection .

Tolkien himself didn’t publish many books during his lifetime, but he left an immense amount of notes and more or less completed manuscripts that his son, Christopher, edited and published after his father’s death and until his own death in 2020. I have read some of these books, but not all of them. A small part of me wants to spread them out because I know that sooner or later I will have read them all and that will be a sad day. However, these are books with such a wealth of detail that you can read them many times and still discover new things to enjoy. I have read Lord of the Rings a lot of times over the years, and still finds new things to pique my interest every time. When you get older, you also read with different eyes, and see the text in other ways. It is a completely different experience reading these books now than it was twenty years ago.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Tolkien’s death, I decided to sit down and take a closer look at one of Tolkien’s alphabets, namely Tengwar .

Tengwar

Tolkien was a professor of language and literature at Oxford University. From a young age he had a hobby of creating his own languages, and his mythology was created in part as a world he could put these languages into. The most developed of these are the two elven languages: Quenya and Sindarin. Both of these have glossaries of several thousand words, as well as fully developed grammar and syntax. To get an idea of how big this work was, and how many languages Tolkien actually constructed for his Middle Earth mythology, the website ardalambion.net by Helge Kåre Fauskanger is a wonderful resource. It’s a relatively old website that doesn’t seem to’ve been updated for a while, but his articles are extremely thorough.

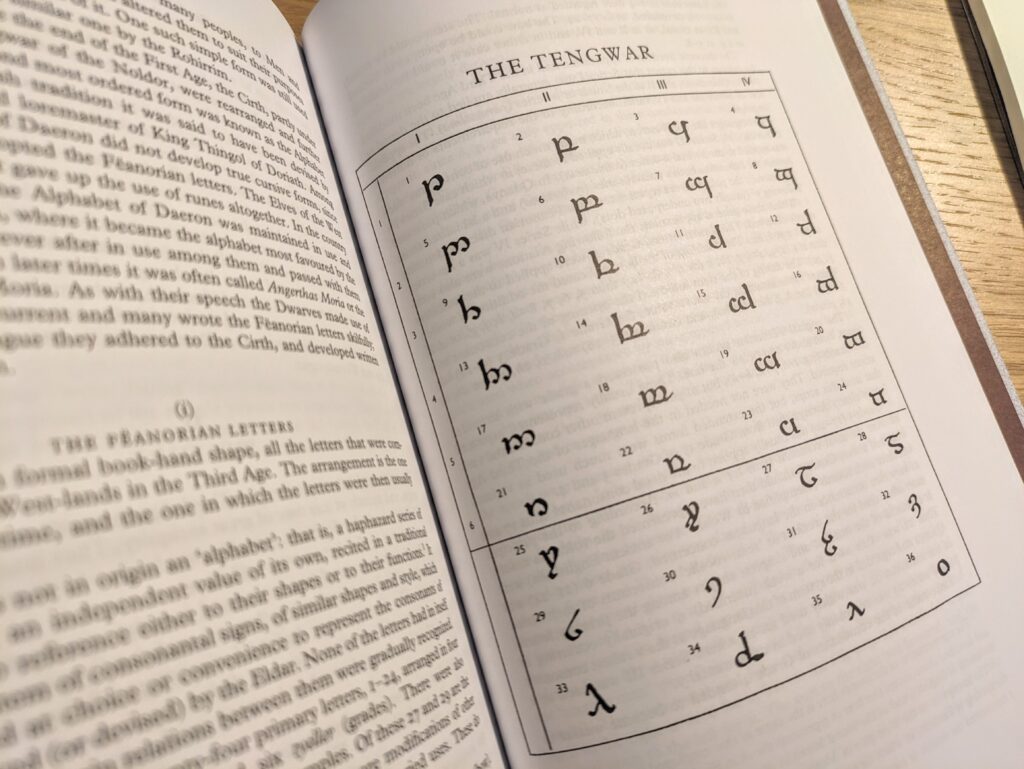

In addition to a good number of languages, Tolkien also constructed some alphabets. The two most famous of these are probably Cirth and Tengwar. Cirth is based on Norse runes, and in Tolkien’s world often used by the dwarves. Tengwar is a bit more unique, in that it doesn’t seem to have been directly influenced by any existing alphabets in the real world. According to Tolkien, it was developed by the legendary elven smith Fëanor in the First Age. It’s a distinctly Elvish alphabet, but is also used by other peoples in Middle Earth. Tengwar is particularly interesting, because it is quite complex, and Tolkien never gives a definite explanation on how it should be read/written. There are a few pages in Appendix E of The Lord of the Rings that describes it, but Tolkien by no means makes it easy for his readers. Different versions of the Tengwar script are given based on languages, peoples and different cultures who all used it in different ways, adapted to their needs. There’s not one correct recipe for how to write Tengwar. The two Elvish languages, for example, have different ways of using it. The inscription on the ring, which is written in Black Speech, is a third variant, and on the west gate of Moria we find a fourth way of using it. All of these are so different that it can be challenging to interpret if you try it with the “wrong” set of rules.

A fifth variant is the Tengwar script on the frontispieces of Tolkien’s books. These are in English, and here Tolkien has adapted the alphabet to English sounds. Tolkien’s son, Christopher, who published many of his father’s manuscripts after his death, also has some examples of Tengwar that deviate slightly from the way his father used it. The whole thing is further complicated by the fact that Tengwar is a phonetic alphabet, so the notion of “correct” spelling is thrown right out the window.

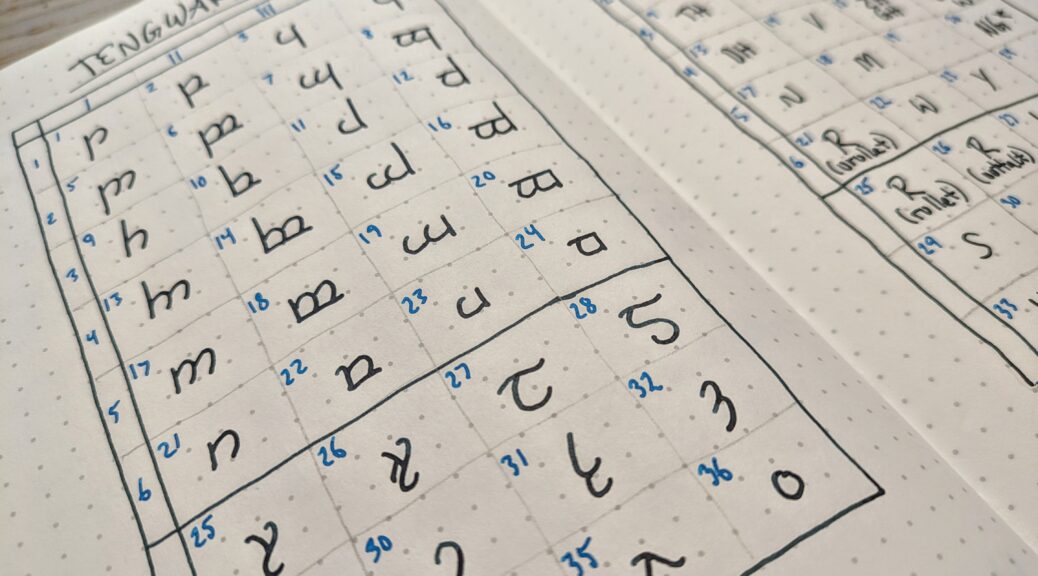

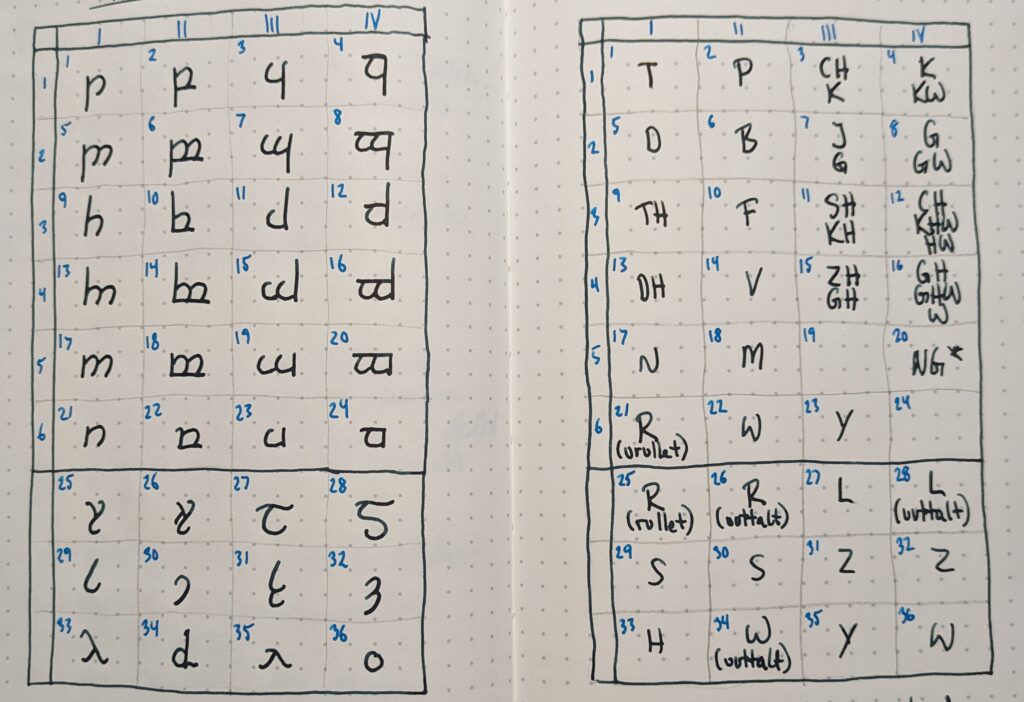

In other words, there are many variations out there, but Tolkien gives – albeit a little reluctantly – some suggestions for how most of the letters can be used. Roughly speaking, it looks something like this:

The important part is that related sounds should also have letter forms that are related to each other. In addition to that, the letters can be placed slightly differently in the chart, based on the linguistic needs you have.

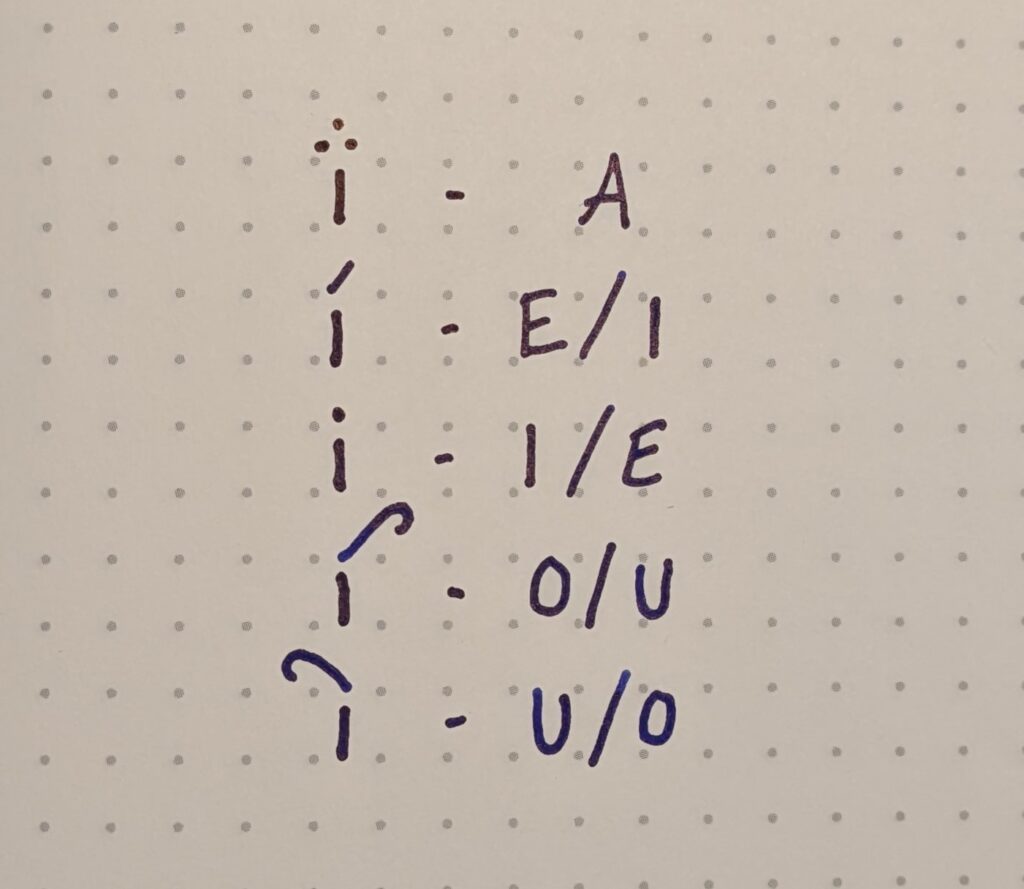

This is a system of letters that is easy to adapt to different languages, as you can give the different letter forms different sounds based on what is used most in the language. The same applies to the placement of the vowels. The vowels do not have their own letters, but are written using various accents and marks that are placed above the connecting consonants. It depends on the language whether they are placed above the consonant that comes before or after the vowel in question. Tolkien writes that in the High Elvish language Quenya, which often have vowels at the ends of words, they are often placed above the consonant that comes before the vowel, while in Sindarin, the more informal and everyday Elvish language, it is relatively rare for words to end with a vowel. Here the vowel are placed over the following consonant. In the writing on the frontispiece, which is in English, the vowels are on the following consonants, and this is how it’s usually done in other languages as well.

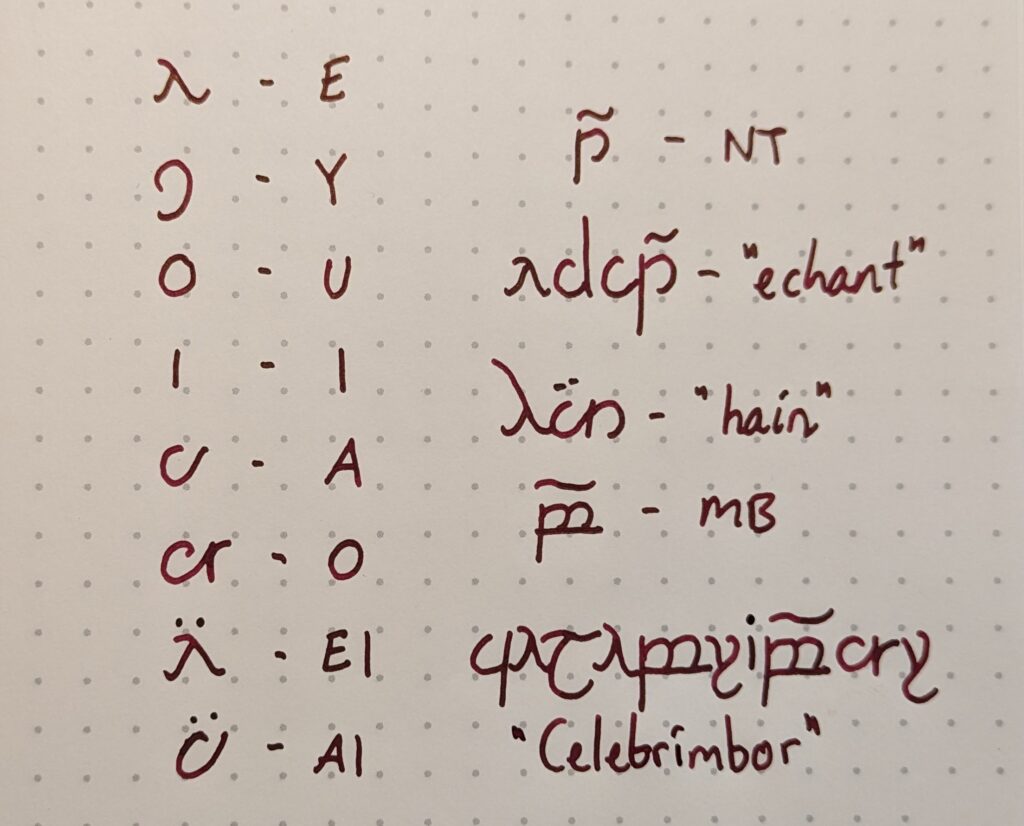

Here we have an overview of the vowels. If there are no connecting consonants to place them over, you can use a stem that looks like an “i” or a “j”, and replace the dot with the correct vowel mark. “E” and “i” are related, as are “o” and “u”. It varies quite a bit which of them is which.

Let’s take a closer look at some concrete examples.

The Lord of the Rings

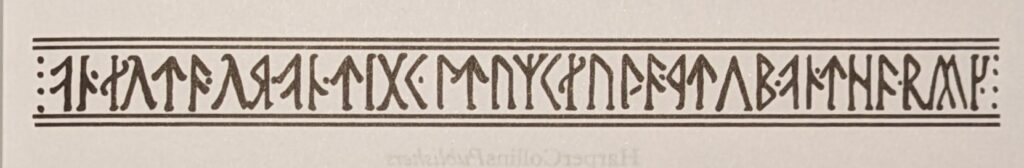

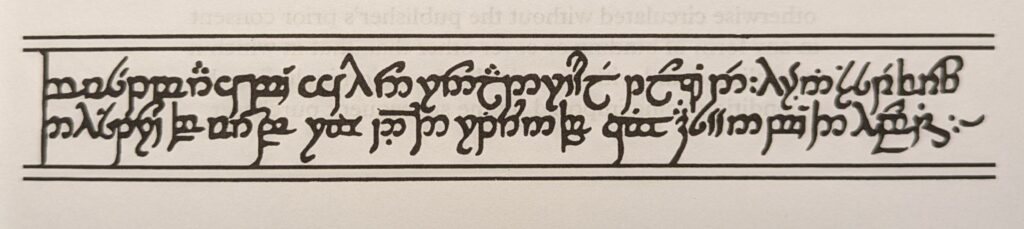

On the cover of The Lord of the Rings it says at the top (in Cirth runes): “THE LORD OF THE RINGS TRANSLATED FROM THE RED BOOK”, then the sentence continues at the bottom of the page, in a more complicated Tengwar. If you use Tolkien’s own explanation of the alphabet from the appendices, you end up with this:

«VWESTMARCHBEJHONRONALDREUELTOLKIEN : HERINIZSETFORTHDHISTORI[?]WOR[?]RI[?][?]DRITURN[?]KI[?AZSEENBEDHHOBIT[?]»

After some deciphering and interpretation, this can be read as: “of Westmarch by John Ronald Reuel Tolkien : Herein is set forth the history of the War of the Ring and the Return of the King as seen by the hobbits”.

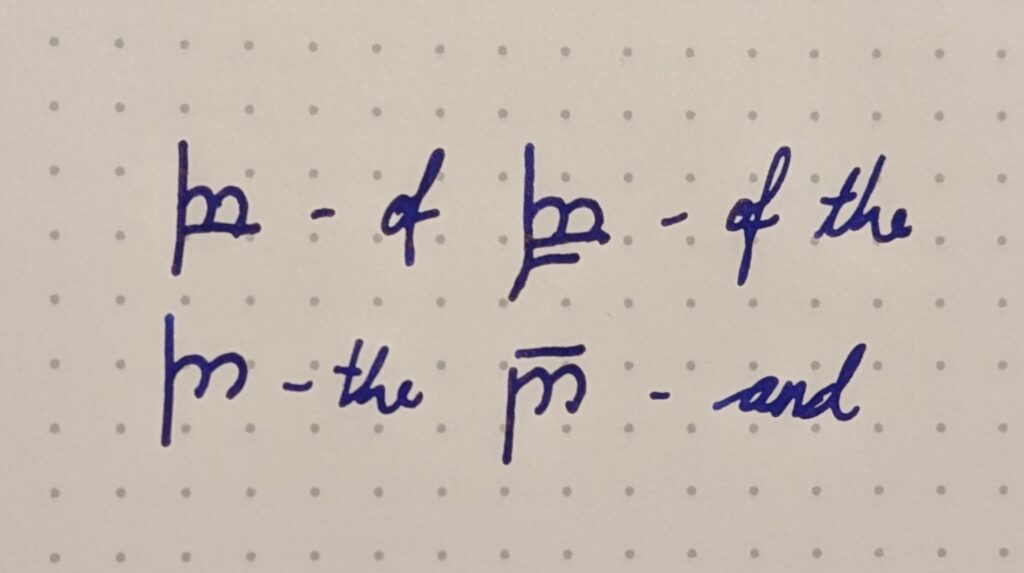

In this example, “i” is written with a dot, and “e” with an accent. “O” is written with a curl upwards to the right. In the sentence, Tolkien uses some letters/letter combinations that are not explained in Appendix E. From the context, you can figure out that he has made a few special characters that are used as a kind of abbreviation for “of”, “the”, “of the”, and “and”.

As “ng” at the end of the words “ring” and “king”, he uses a letter which is set up in the chart (no. 20), but not explained. However, it is on a row devoted to the nasal consonants (“n” and “m”), so it makes sense that it could be used for “ng”. The last letter in the word “hobbit” has an extra curl, which I think means that the word should end with an “s”, i.e. the plural form “hobbits”, which makes more sense, as we follow four hobbits in the book. This curl is not explained either, but from the use here and in a few other examples, you can see that this is probably what was intended.

The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales

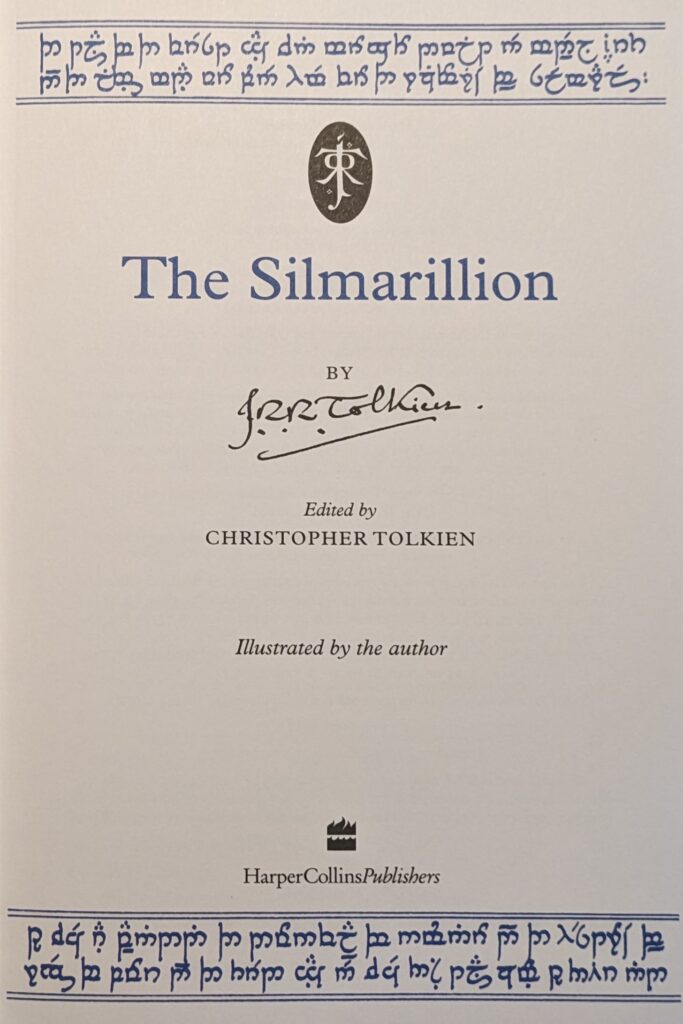

On the cover of The Silmarillion is the following, in Tengwar:

«The tales of the first age when Morgoth dwelt in Middle Earth and the elves made war upon him for the recovery of the silmarils»

«to which are appended the downfall of Numenor and the history of the rings of power and the third age in which these tales come to their end.»

In this version of Tengwar, the characters for “i” and “e” have switched places compared to the Lord of the Rings frontispiece, so that the “e” is now a dot, and the “i” is an accent.

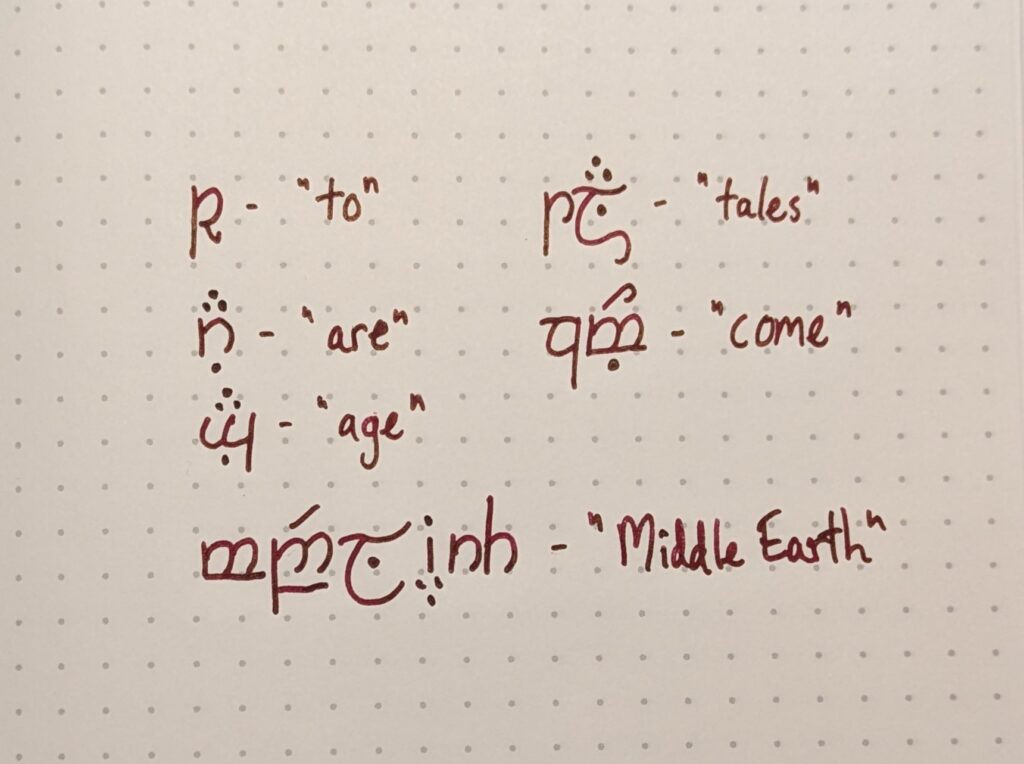

There are a few other interesting things here too. For example, take a look at the first character of the lower inscription. This is a “t”, with a curl underneath, which in this case is read as the word “to”. There are a few more examples here too of vowel signs being placed under the consonant sign (instead of above). The word “are”, is a good example, where you have the “a” character placed above the “r”, while the following “e” is placed below. We also see it in the word “tales”, which occurs a couple of places, where the “a” is placed above the “l”, and the “e” below. In this word we also get a new example of a curl which means that the word ends in “s”.

In the word “Middle Earth” we also see examples of this, where the “e” in “Middle” is placed under the “l”, and the “e” and “a” in “Earth” are combined. Here we also see that you can use a horizontal line under the letter to mark that it is a double consonant, as under the “d” in “Middle”.

In other words, to understand Tengwar well, you can’t just read the explanation in The Lord of the Rings, Appendix E. You also have to actually take the time to analyze the examples that exist from Tolkien’s own hand, as he has added things, or made small changes and variations in the way he himself uses the script, which is not explained in the book. The inscription on the cover of The Silmarillion was probably made by Christopher Tolkien, who had his own way of doing things, and not exactly the same as his father.

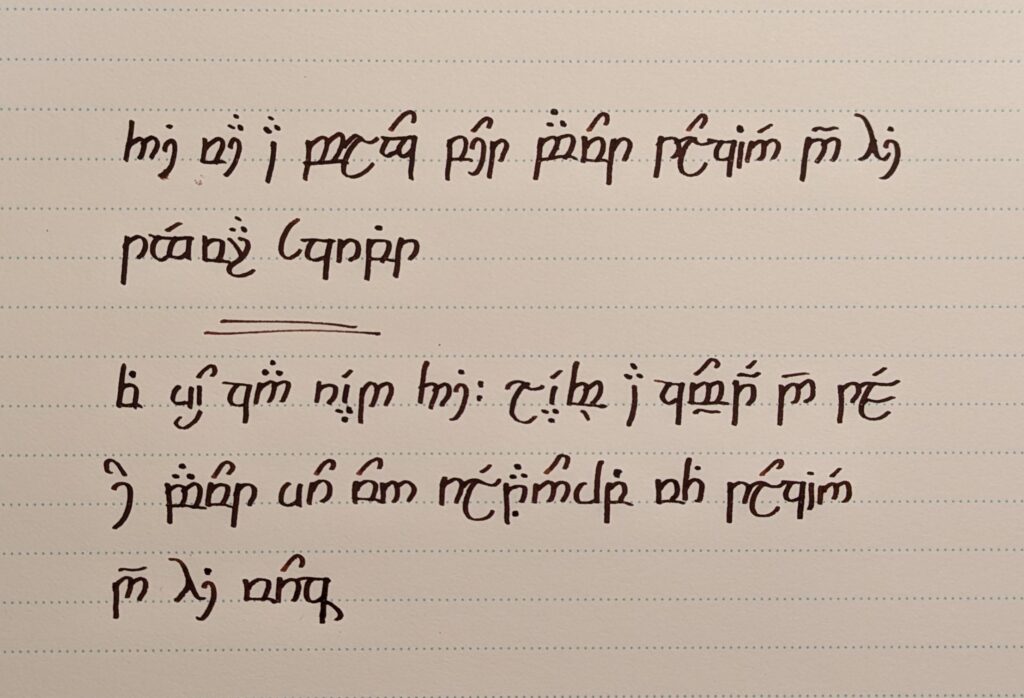

Above, we see the frontispiece for Unfinished Tales. The same rules apply here as in The Silmarillion:

«In this book of unfinished tales by John Ronald Reuel Tolkien which was brought together by Christopher Reuel Tolkien his son»

«are told many things of men and elves in Numenor and in Middle Earth from the elder days in Beleriand to the war of the ring and an account is given of the druidain and istari and the palantiri».

Let’s look at a couple of examples where Tengwar is used as a device the stories themselves:

The ring inscription

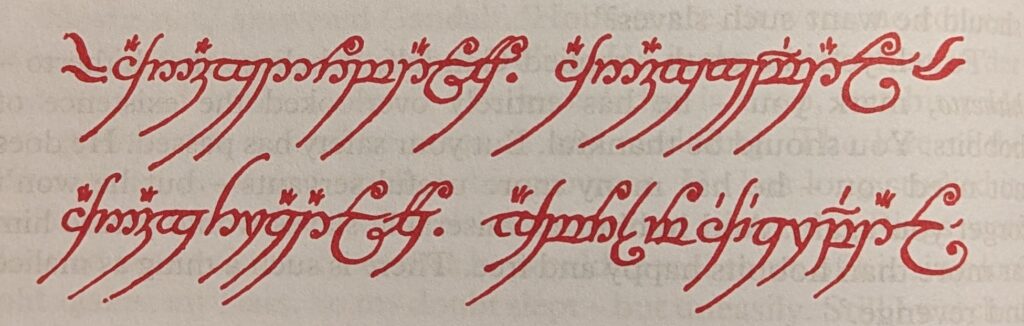

The inscription on the ring itself is a text in Black Speech. Directly transcribed from the writing on the ring, it could be read like this:

«ACHNAZGDURBATULUUK – ACHNAZGGIMBATUL – ACHNAZGTHRAKATULUUK – AGHBURZUMICHIKRIMPATUL»

The actual text is: “Ash nazg durbatulûk, ash nazg gimbatul, ash nazg thrakatulûk, agh burzum-ishi krimpatul”, or in English: “One Ring to rule them all, one Ring to find them, one Ring bring them all and in the darkness bind them”. This is a quote taken from the well-known verse at the very beginning of the book, which describes the rings of power.

In this version of Tengwar, there are some elements that are slightly different from the other Tengwar modes. The most obvious change is the curls that represent the letter “u”. Normally, they would have an opening to the left, while the “o” goes up to the right, but here the right-hand curl is used to reproduce the letter “u”. Tolkien explains this by saying that the right curl was considered more beautiful and desirable, and as the letter “u” was used a lot in Black Speech, while “o” hardly occurred at all, they swapped the two curls for “u” and “o”.

There’s another element in use here as well, which Tolkien barely touches on in the description of the alphabet in Appendix E, and that is the horizontal line over the letter to indicate that there should be a nasal sound (” n” or “m”) before the given consonant, as in the words “gimbatul” and “krimpatul”, where “m” comes before, respectively, “b” and “p”. The vowel mark is then placed above this horizontal line.

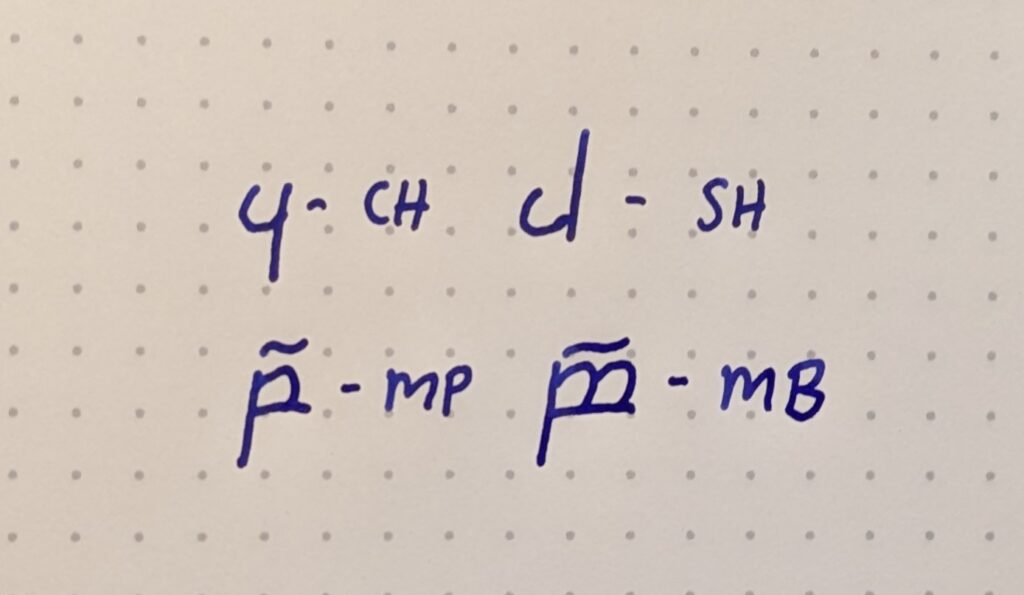

Another thing worth noting is the use of the “ch” letter (number 3 in the chart), instead of the “sh” letter (number 11). It may be that Sauron’s version of Tengwar had the “sh” sound on character 3, but what’s probably more likely, is that this was done to signal that it’s a short and succinct sound, and not a long and soft “sh”. Much like the sound at the end of my name, Anders (which is pronounced “Andesh, with a short “sh” sound at the end):

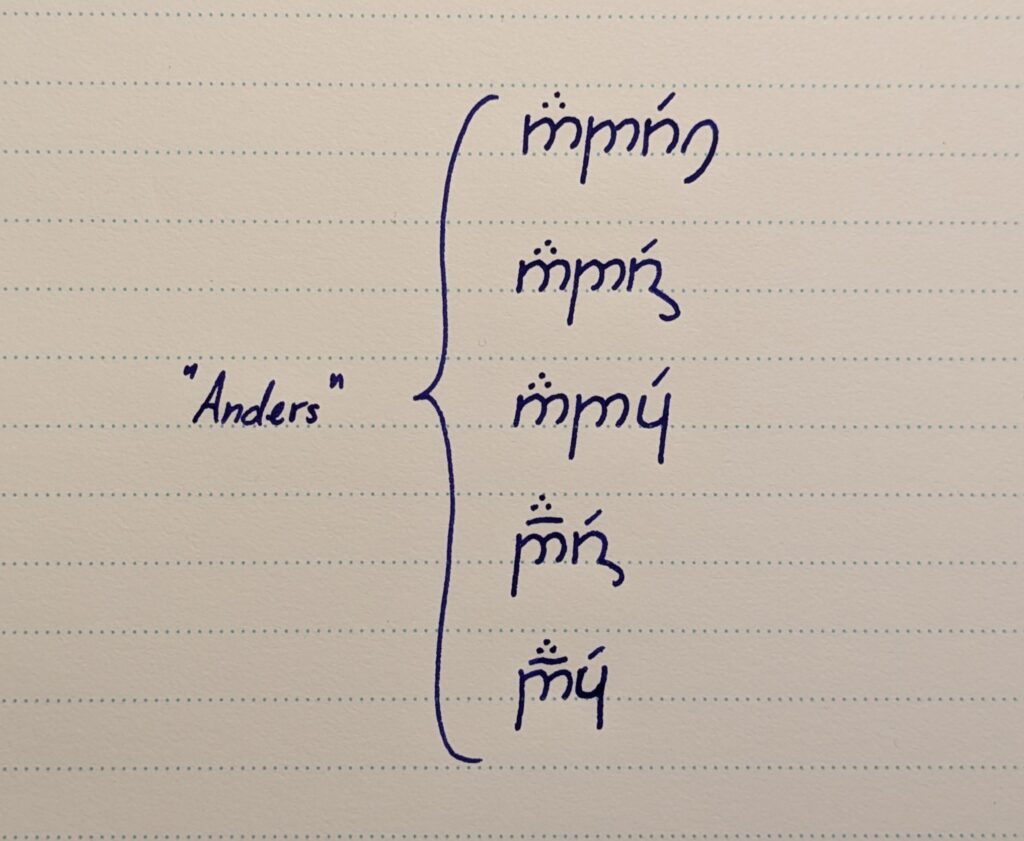

Here we see five different ways to write my name. As far as I can understand from the way Tolkien himself used the Tengwar, all five spellings could be correct, and it primarily depends on how you yourself want it to look on paper. In the top version, the name is printed as Tolkien explains the alphabet in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings. In the next example, I’ve shortened it slightly by using an “s” curl, in the same way Tolkien does in the word “hobbits” on the frontispiece of The Lord of the Rings. In the third example, I use the “ch” sound to replace “rs”, with the same result as the word “ash” in the ring inscription. In the fourth example, I have abbreviated “n” and “d” by putting a horizontal line over the “d”, thereby marking that it should have a nasal sound first. In addition, I use the “s” curl at the end. In the last example, I have done the same with “n” and “d”, but use the “ch” character at the end. By doing this, I have halved the length of the name compared to the top example.

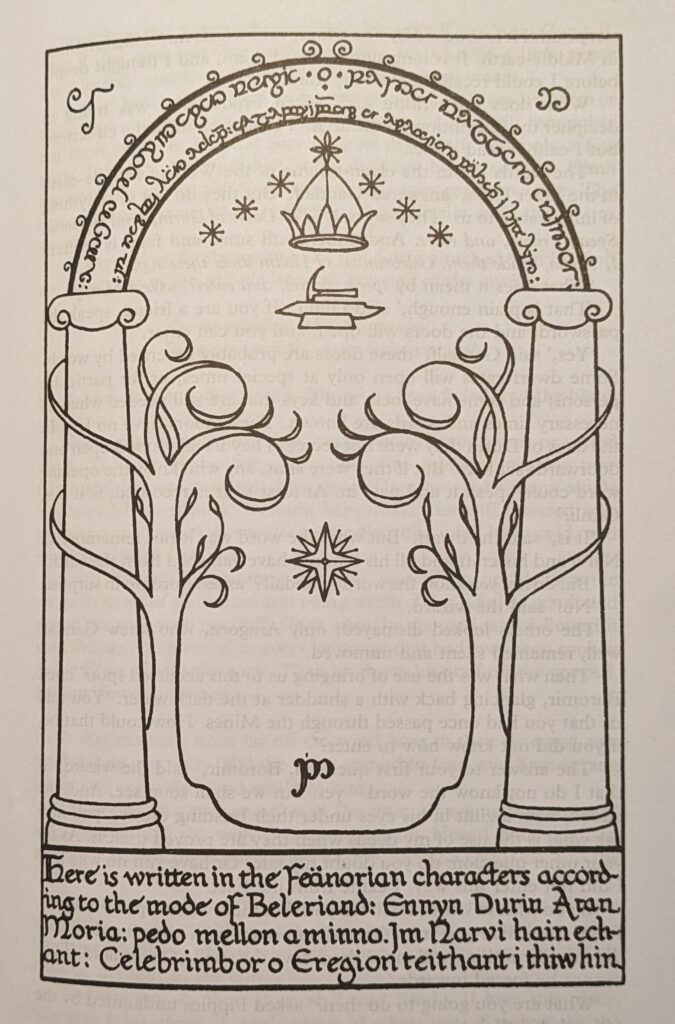

The West Gate of Moria

I would like to say a little about the inscription on Moria’s West Gate as well. It stands out quite a bit from the other Tengwar examples we have, and is almost unreadable if you don’t know what it says, even if you use the Tengwar charts from the back of the book. Frodo (the main character of the book) also states that he is unable to read it, although he can read Tengwar as the elves write it in his time. You get the feeling that the writing has gone through a development throughout the millennia that have passed since the gate was built, and until the fellowship arrives at the gate in The Lord of the Rings. Fortunately, Tolkien gives us the text in this case, which makes it a little easier to figure out.

One of the biggest differences is that instead of placing the vowels as ornaments above the consonants, here they’ve been given their own full characters:

A few dots and dashes are also used. Two dots appear above a vowel sign when it is a diphthong with “i”, as in the words “hain” or “teithant”. Otherwise, a horizontal line above the consonant is also used here to indicate that a nasal sound should come first, as in “echant” or “Celebrimbor” in the examples above.

As if that wasn’t enough, “n” and “m” also have different characters on the west gate than in other modes of Tengwar. In the chart, these two letters have been moved down one row, from 17/18 to 21/22, thus taking the two characters that in later standard versions of Tengwar are used for the unrolled “r” and “w”.

Conclusion

Tolkien is seen by many as the ultimate world builder. Tengwar is only a tiny part of the world he created, but gives a small insight into how he worked with every little detail to give his world a life and a history. Tolkien is also often cited as the definite example of the world builder who gets so caught up in all the details of his own world that he is never able to actually complete his stories.

The Hobbit was published in 1937, and in October 1938 Tolkien wrote in a letter to his publisher that he hoped he would have the sequel ready “early next year”. Time and time again he got hung up on small details, which caused him to procrastinate, and time and time again over the next several years he wrote in new letters to the publisher that he was almost finished. The Lord of the Rings didn’t come out until in 1954, seventeen years after The Hobbit. His real magnum opus, the Silmarillion, which contained the entire mythology The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings was placed in, he worked on from his early twenties until his death. It was his son, Christopher, who finally put it together and published it in 1977, four years after his father passed away.

The result of this extreme world-building was that Tolkien himself never felt “done” with things. However: when the stories finally were published, they were so elaborate, so incredibly rich in detail, and set in a world much, much larger than the story itself. And you notice that as soon as you open his books.

With the information in this blog post, you should be able to decipher this text, and follow the prompt:

2 thoughts on “Nibby Sunday – Tolkien and the Fëanorian Letterforms”

Bravo. Your blog comae recommended to me just today and this post is amazing. Even though a fan, I failed to appreciate the language. Laziness on my part. Armed with your explanation, I am going to undertake the same exercise with my name. All the best

Thank you! I’m glad you enjoyed it 🙂