Point to Paper – Why did the Parish Priest Lund send a letter from Tangen on Tuesday the 18th of October 1808 to the County Physicist Arbo and City Surgeon Lundt at Bragernes?

Written by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy and translation of Norwegian Gothic handwriting by Gina Dahl

I recently bought a stack of old Norwegian handwritten letters from a collector in Sweden. All are from the early 19th century. In this pile, there was one letter that caught mye eye. It just cried out to be investigated further.

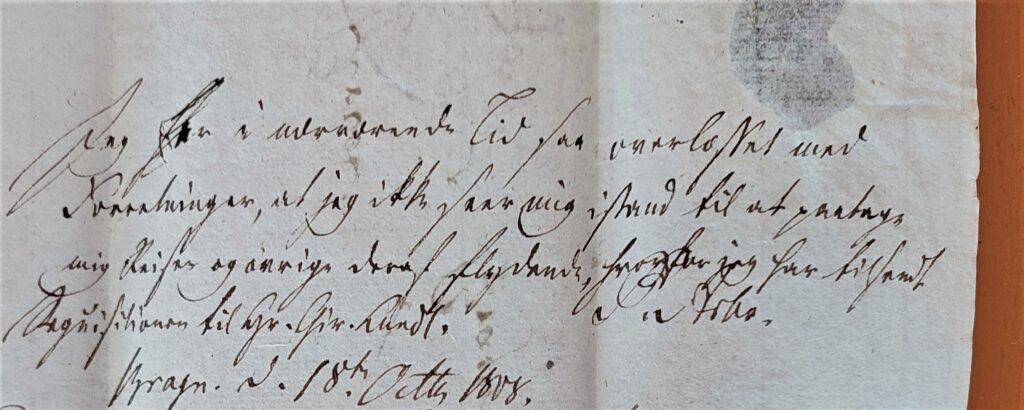

The letter is from 1808 and is written with a quill pen. Quill pens were usually cut by hand by the person writing. They were cut with a small knife, preferably a folding knife, which was specially made for the task. Folding knife in English is precisely often called “pen knife”. The freshly cut feather was then dipped in ink and was ready for use. The quill pen could be used to write a few words before it had to be dipped into the ink again. Unfortunately, the quills quickly wore out and had to be constantly resharpened. You can actually see the variations in the wear if you study the writing in such a letter carefully. The mass produced pen nib came in 1822. It enabled smoother writing and could be used to write many letters before it wore out. The pen nib in metal made for dipping is by many considered to be the first industrially produced disposable item.

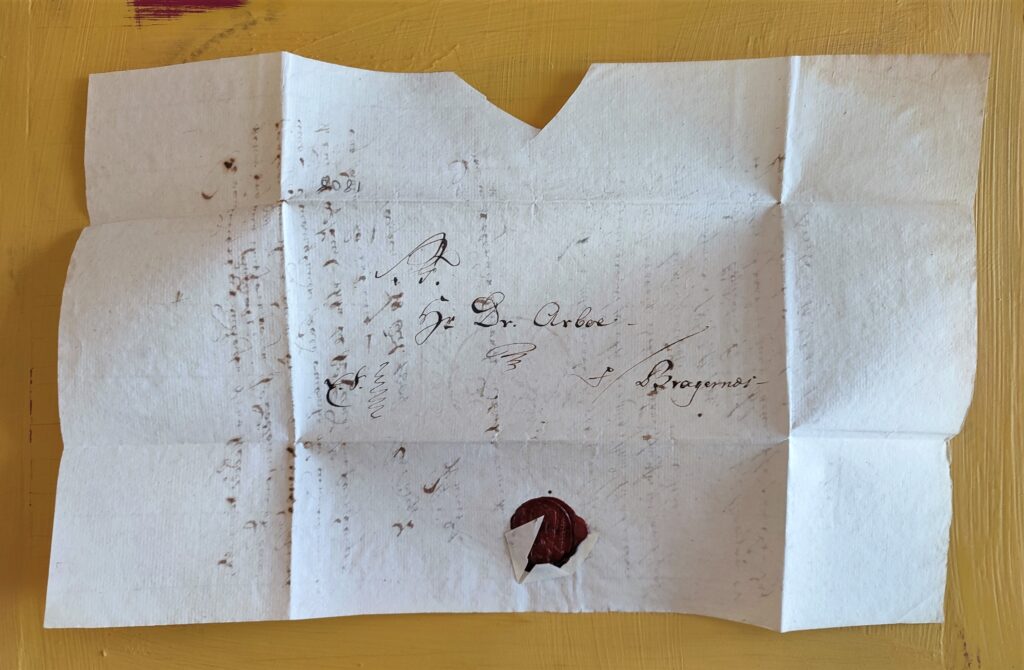

The letter you are now going to find out more about was delivered by a messenger. The sender actually refers to the messenger in the letter itself. Although it was forbidden in Norway to transport parcels and mail in competition with the postal service, there were exceptions for carrying mail locally and in the cities. Local messengers could deliver a letter immediately. They were also willing to wait at the recipient’s house and take an answer back with them to the sender if it was urgent. This letter is an example of how effectively the scheme worked. This letter has moved between three people in less than two days.

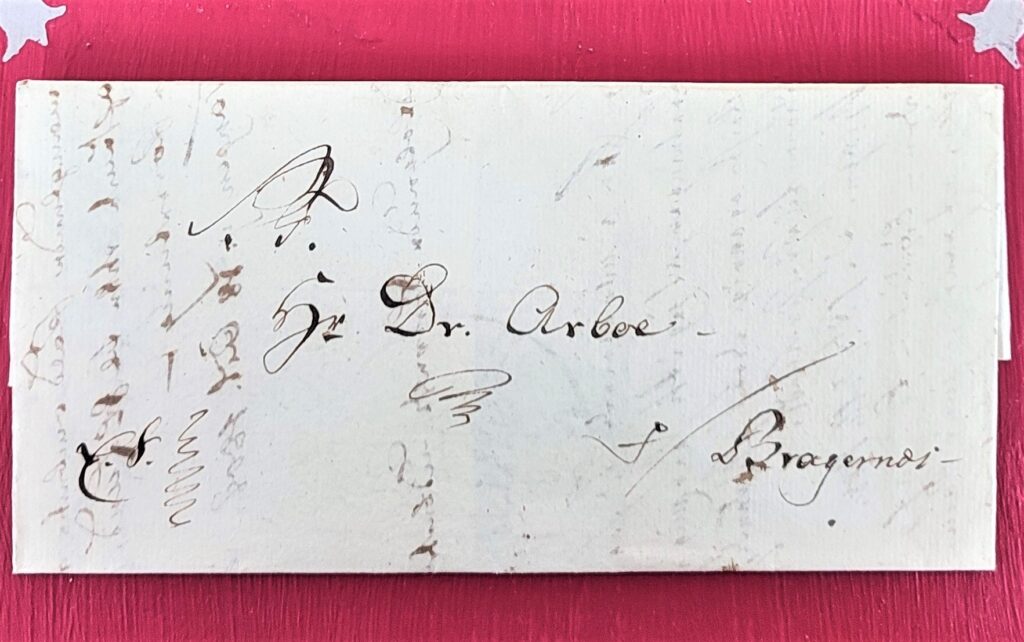

The letter was addressed to Mr. Dr. Arboe living at Bragernes. I am quite sure that it is Mr. Doctor Medicinae Peter Arbo (1769-1809). He was county physicist in Buskerud from 1806-1809. In most sources, his surname is written without the “e” (Arbo[e]). For those who are not familiar with the local area, Bragernes is today part of the city of Drammen. I sit at my desk at Galterud and look out at Bragernes. Galterud became part of Drammen in 1964.

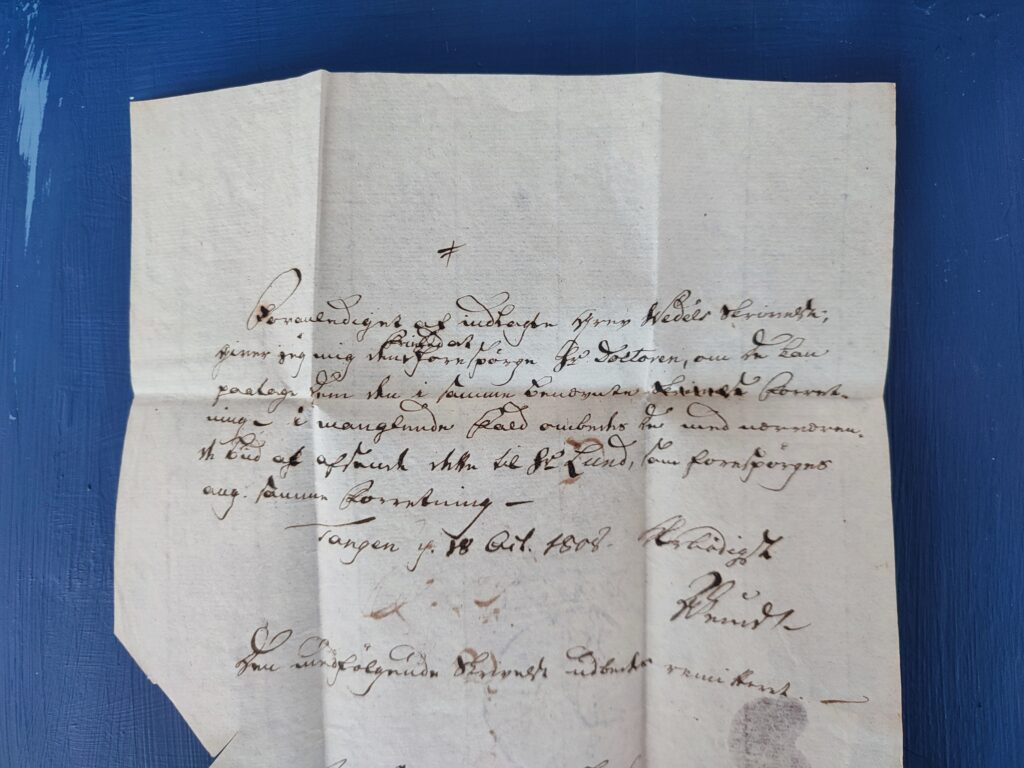

Although I am not quite sure who the sender was, I think it must have been the parish priest in Skoger and Tangen. His name was Andreas Jacob Lund. Whoever writes the first part of the letter signs with ALund . I think the “A” stands for Andreas. The letter is sent from Tangen. Lund is described as parish priest for both Skoger and Tangen in this link . He signs the letter: Tangen d. 18 Oct. 1808. Most Reverend ALund . Tangen is today also part of Drammen.

The first recipient of the letter is Dr. Arbo. He writes his answer and sends it on to Mr. Stadschirurgus (City Surgeon) Andreas Friedrich Lundt (1762-1831). Lundt is referred to in a number of sources as both Bataljonschirurgus (Battalion Surgeon) and Regimentschirurgus (Regiment Surgeon).

On the 19th of June 1811, just three years after the letter I am now examining was written, the towns of Strømsø and Bragernes were merged into the market town of Drammen. The area of Tangen was also a part of this merger. Dr. Arbo died before this happened. In 1812, a bridge was built over the Drammen River. The merchants at Bragernes were skeptical about the bridge project. There was concern that there would be trade leakage to Strømsø. The bridge was therefore strictly regulated with tolls and fees.

Over time, the population of Drammen has had many different experiences with both bridges, mergers and tolls. Changes always create debate. It is only a few years since we finally got rid of the toll station on the motorway that goes to Oslo. The joy was short-lived. It did not take long before the neighboring municipalities got their own toll stations. Now it seems we pay toll to everyone else.

Drammen municipality was also recently merged with both municipalities of Nedre Eiker and Svelvik. It was good for some and to the frustration of others. I have an aunt in Nedre Eiker who has strong opinions about the matter. Right now, another new bridge is being built between Bragernes and Strømsø. Centuries of debate tradition are thus well preserved. As usual, there have been years of bridge planning and discussions. This time it is the architecture and the price that have created the most commotion. The only thing we know for sure is that the new bridge will not be cheap. We at least hope it will turn out to be beautiful.

I always feel a tingle in my stomach at the clues that old letters trick me into following. Maybe this time I could get to know something of the past of the area I live in. Maybe I could also uncover some forgotten history. As always, I depend on some good helpers. Together we have found out a lot. In particular, I would like to give credit to the Senior Academic Librarian Gina Dahl at the University of Bergen. She has helped me on several occasions. Among other things, she has contributed with transcribing two letters I have written about previously. Although I practice deciphering old Norwegian Gothic handwriting, I still struggle. I still need some help.

The letter Gina translated for me in the autumn of 2021 was addressed to Customs Treasurer Christie. The letter was from 1858 and was possibly written by his son Johan Andreas Budtz Christie. I think it was one of the most read posts for our Norwegian blog in 2022. We received positive reactions and inquiries from all over the country. Several pointed out that Johan Andreas Budtz Christie belonged to an enterprising group of siblings. He had a brother who in his time was a leader and architect during the restoration of the Nidaros Cathedral. He had another brother who contributed to the drawing of a map of Orkdal and the surrounding area. He himself became a much-loved priest in Vikøy congregation in Hardanger. Here is a link if you want to read the post: Kjartan verses – 16-year-old in trouble in 1858 writes letter to dad.

Gina was also the one who transcribed a letter written by Baron Wedel-Jarlsberg in 1840. Here is a link if you want to read that post: The Baron who tried to headhunt a tutor for his sons. Baron Fredrik Wilhelm Wedel-Jarlsberg was looking for a tutor for his sons. He tried to tempt Mr. Candidat Thue to take the job. Thue had just received the best grade in his civil service examination in philology. He was therefore sought after. The baron was willing to offer a generous salary if he took the job. In the introduction to the letter I am writing about today, a relative of the baron is mentioned. I think the relative is Count Johan Caspar Herman Wedel Jarlsberg (1779-1840). He became county commissioner in Buskerud in 1806.

The letter Gina has transcribed this time was written in 1808. Lund, Arbo and Lundt are historically interesting people. That makes the investigation much easier and much more fun. Parish Priest Lund I will write more about in a future post. Arbo and Lundt worked actively to improve the general state of health in the population. They were particularly concerned with the area they worked in. They were also advocating for educating midwives in order to professionalize birth care. They were both frustrated by “the wise old women” who, among other things, they believed contributed to an unnecessarily high infant mortality rate.

Even before I had the Gothic handwriting translated into comprehensible Norwegian, I was therefore aware that the persons to whom the letter was addressed were promising in terms of further exploration. The text is only a few lines, but I find that such letters can be difficult to interpret when they are as old as this. I know that Gina Dahl does not initially take on the task of deciphering old letters. At the same time, I know that she has worked on medical history. I therefore hoped that this particular letter might be exciting for her. Fortunately, Gina allowed herself to be tempted. Thanks to her, you will have the opportunity to get to know the entire content of the letter. It comes a little further down in the post.

Andreas Friedrich Lundt and Peter Arbo are mentioned in the first official national medicinal report from 1804. The Norwegian Health Authority published a transcribed version of this in 2004. The foreword, which was written by director of health Lars E. Hanssen, states:

Retired county doctor Hans Petter Schjønsby has taken on the task of transcribing the medicinal reports for the year 1804. (…) The medicinal reports from the counties are to this day an important source of information for the Norwegian Health Authority. (…) The purpose of the medicinal reports in their first year of 1804 is thus strikingly similar to the purpose of the current system: namely to obtain professionally justified observations and advice from the civil servants who have first-hand experience to build on.

I can thank this publication for much of the historical information used in this post. Here is a link to the report: A look back at the first year of a traditional report . It is written in few words and is easy to read. It is an exciting read about the health situation across Norway just over 200 years ago. I have also found interesting material on the website of Lier Municipality under the title Health and illness . This short text contains dramatic descriptions of illness and death in the municipality in the same period.

Mr. Stadschirugus Lundt and Mr. Dr. Amtsfysikus Arbo were pioneers in several areas. When would you guess that the first vaccine was given in Norway? Here too, Drammen can boast of long traditions. Lundt administered the first smallpox vaccines as early as 1803/1804 (12). The very first smallpox vaccine was given in Norway in 1803 in Kristiania. What was soon to become the city of Drammen was thus among the first places in Norway to give vaccines. From 1810, the smallpox vaccine was required for all children before confirmation age.

Lundt was also concerned about the sailors who came home from international shipping. The sailors, and a large number of returning soldiers, caused a number of problems on their return. The Napoleonic Wars had just begun (1803-1815) and there was a steady stream of soldiers who had participated in both this and other conflicts. Lundt claimed he could document that the soldiers and sailors brought serious illnesses with them to Drammen. He was particularly concerned about all the cases of venereal diseases.

For most of these diseases there was little to be done. The doseases contributed to much suffering both physically and mentally. Treatment was often futile and dangerous. It usually consisted of bloodletting and the use of mercury. The diseases Radesyke (a name used for a collection of diseases that had some similarity), Syphilis (sometimes also referred to as Radesyke) and Gonorrhea were widespread. They affected both the so-called guilty (those who were infected through sexual activity) and the innocent (those who were infected in other ways). Since the diagnosis was uncertain, and there were a number of epidemic diseases with similar symptoms, there were many innocent people who were unjustly labeled as having lived a debauched life. All diseases that gave similar symptoms to venereal diseases were associated with shame. “Wise old women” and doctors often used the same treatment methods. In many cases it could be debated who were actually quacks and who were not. You can read more about it here: Mercury, bloodletting and animals were weapons in the fight against the shameful epidemic of the 18th century .

Mercury was both exotic and magical. Something as mysterious and incomprehensible as liquid metal just had to be both healthy and healing. The belief in mysterious ingredients, exotic drinks and imaginative treatment methods holds up well even in 2023. I myself am moderately optimistic about the benificial health effects of my daily dose of warm milk (golden milk) with turmeric, pepper, cardamom, cinnamon and ginger. I drink it with a slightly blushing faith in my heart. Without a direct comparison, I get associations with the sports drink Prime, which is currently being torn out off the shop shelves. The miracle drink has influencers as role models and is bottled in cool, colorful bottles. No wonder it seems healthy for the body and strengthening for the muscles.

Mercury was at this time popular for many purposes. There was still little knowledge of the dangers. You can read more about mercury in my post The hatter’s feud, the sheriff and the daughter-in-law . Among other things, mercury was used to make the finest hat felt. It was also used to extract precious metals. Unfortunately, this still happens. Of course, mercury also had to be suitable as a medicine against syphilis. Today we know that mercury makes people and nature sick. We also know it’s what made the hatters crazy.

Lundt and Arbo were among those who fought for the education of midwives. They even believed that training midwives should be paid. As a terrifying example, the child mortality in the municipality of Lier in 1773 increased from 25% to 85%. It was both about the fact that contagious and dangerous epidemics were going on and that “wise old women” were using risky and dangerous treatment methods that were often based on superstition. An average child mortality rate in which every fourth child dies is incomprehensible enough today, but imagine a period in which fewer than two out of ten children survive their first years. In comparison, according to the UN association, the child mortality of the hardest hit country in the world in 2021 was 11.5%. As early as 1803, Dr. Arbo raised the question of the high infant mortality rate with Bishop Schmidt and made suggestions about what could be done. Midwifery education was first established in Norway in 1815.

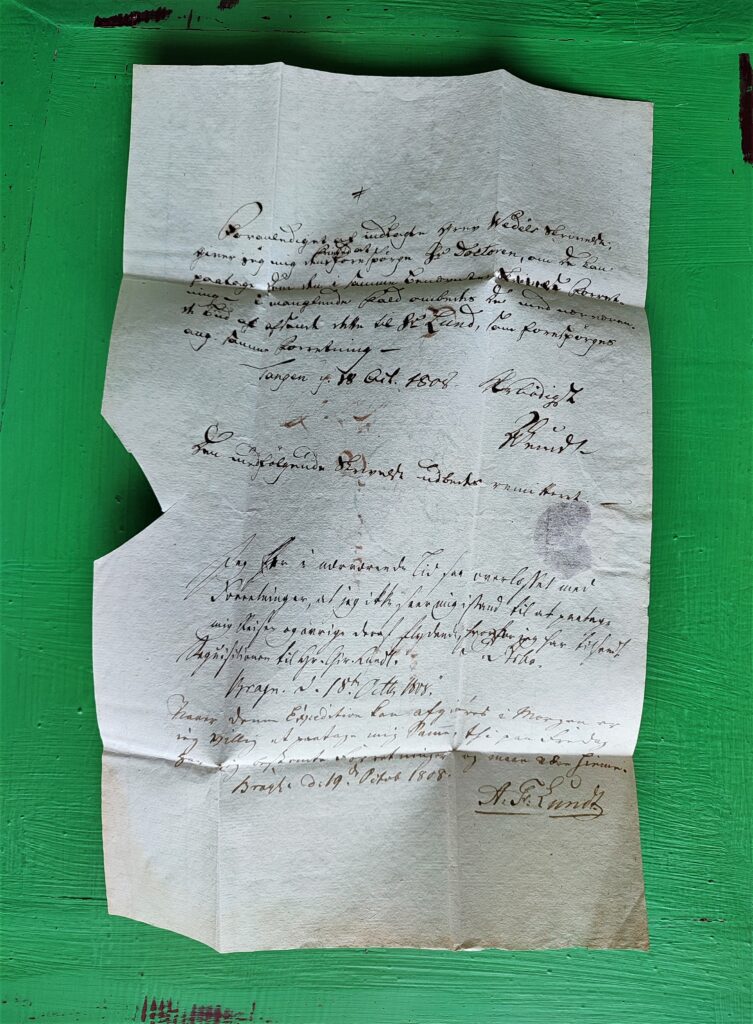

Now it’s time to get down to the text that inspired today’s post. Here is what the letter said:

Prompted by the inpatient Count Wedel’s writing;

I take the liberty of asking Mr. Doctor if you can

undertake it in the same named business.

Failing this, you are asked

to send this to Mr Lund, who is being asked

about the same business.

Tangen d. 18 Oct. 1808. Most Reverend

ALund

The accompanying Letter is requested to be forwarded.

(Here follows Dr. Arbo’s answer on the same letterhead)

At the present time I am so overburdened with

business that I do not see myself in a position to undertake

My Travels and the rest of it fluently, which is why I have sent

the Requisition to Mr. Chir. Lund.

P. Arbo Brage. d. 18 Oct 1808

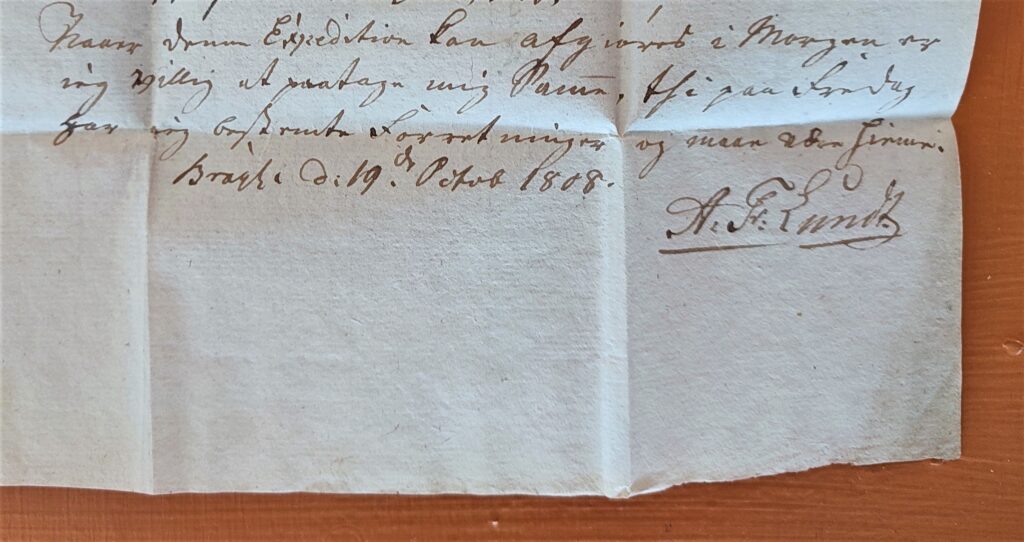

(Finally, Mr. Chir. Lundt’s answer. It also follows on the same letterhead)

If this expedition can be set off tomorrow,

I am willing to undertake the same, because on Friday

I have certain business and must be at home.

brag. d: 19 October 1808

A.Fr. Lund

I do not know what kind of business the letter may be talking about. Unfortunately, I do not have the attached letter from Count Wedel. I’m not even sure who sent the letter. For a long time I thought it was a letter that went back and forth between Lundt and Arbo. Something was just wrong about that theory. It seemed then like Mr. Lund(t), with and without “t”, wrote both from Tangen and Bragernes. He could of course have moved together with the letter, but it looked like he even signed differently when he wrote the first and second time in the letter (ALund and A. Fr. Lund). Now I believe that the sender from Tangen was the parish priest Andreas Jacob Lund (ALund). I am quite sure that the recipients were Mr. Dr. Amtsfysikus Arbo and Mr. Stadschirurgus Lundt. Then the text also fits better in the sense that the original sender no longer refers to himself in the third person and with his own surname. I think parish priest Lund only makes a small typo when he writes that Arbo should forward the inquiry to Mr. Lund (without the “t”). Arbo actually forwards the letter to Lundt.

This letter is being written following an inquiry from Count Wedel Jarlsberg. I am not quite sure if I have found the right count, but there are many indications that the one I have suggested may be right. Something that strengthens this theory is that I have another letter from 1806. It was also sent from Tangen. It is also written by someone called Lund. Both letters use the same lacquer seal and both have very similar signatures. None of the signatures resemble the signature of A. Fr. Lundt. I will examine the letter from 1806 further. I also have a letter from Count Wedel Jarlsberg from the 18th of May 1809, written to parish priest Lund at Tangen. I think that strengthens the theory that it is the parish priest who is the original sender. Parish priest Lund and Count Wedel Jarlsberg had a relationship. I am open to input if you, the reader, know something I don’t.

When the letter writers use the word “business” it also seems to mean undertaking a task. Most tasks, services and goods were linked to money. Both pharmacy services and goods, vaccines, medical care and most other work tasks had to be paid for by someone. There was no welfare state or a public health service similar to what we have today. Even receiving emergency health care from a city surgeon or a county physician had to be paid for by someone. It was thus also a business. In most cases, everything had to be paid for by the patient himself. In 1803 it was proposed to make some differentiations between the poor and the rich. Assisting child birth was to cost 1 riksdaler for fine families, 24 shillings for farm families and 10 shillings for farm tenants. Baptism would be included in the price if you used an approved midwife.

The reason for this was that there was a growing desire for most people to be motivated to use professional healthcare staff. We have gradually enjoyed this professionalization to an extent that most people cannot fathom. We are healthier, fitter and more live longer than ever. The average lifespan of a Norwegian says it all. Courageous health promoters such as Lundt and Arbo dared to believe in this at a time when professional health care could sometimes be difficult to distinguish from the help one could get from experienced “wise old women”. It is important to remember that there were also wise old women that actually were wise. Many ordinary people had valuable experiences that could save lives. Most places did not have a doctor and had to make use of what wisdom was available locally. Sometimes it worked quite well.

The letter was transcribed by Gina Dahl.

All photos were taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy.

References to all websites and texts I have used can be found as links throughout the post. You, the reader, can click on the blue links yourself (places in the text with blue text underlined) if you want to investigate the mystery further.

One thought on “Point to Paper – Why did the Parish Priest Lund send a letter from Tangen on Tuesday the 18th of October 1808 to the County Physicist Arbo and City Surgeon Lundt at Bragernes?”