Nibby Sunday – Dorn / College fountain pen factory

In December 1949, the newpaper Dagbladet announced that a Norwegian fountain pen factory would finally be established, and that it would be located in Ski. Local newspaper Østlandet’s Blad contradicted this rumour. They could confirm that a factory building was to be set up according to the New Deal principle, where several small businesses rented in the same building, but they had not heard anything about a fountain pen factory.

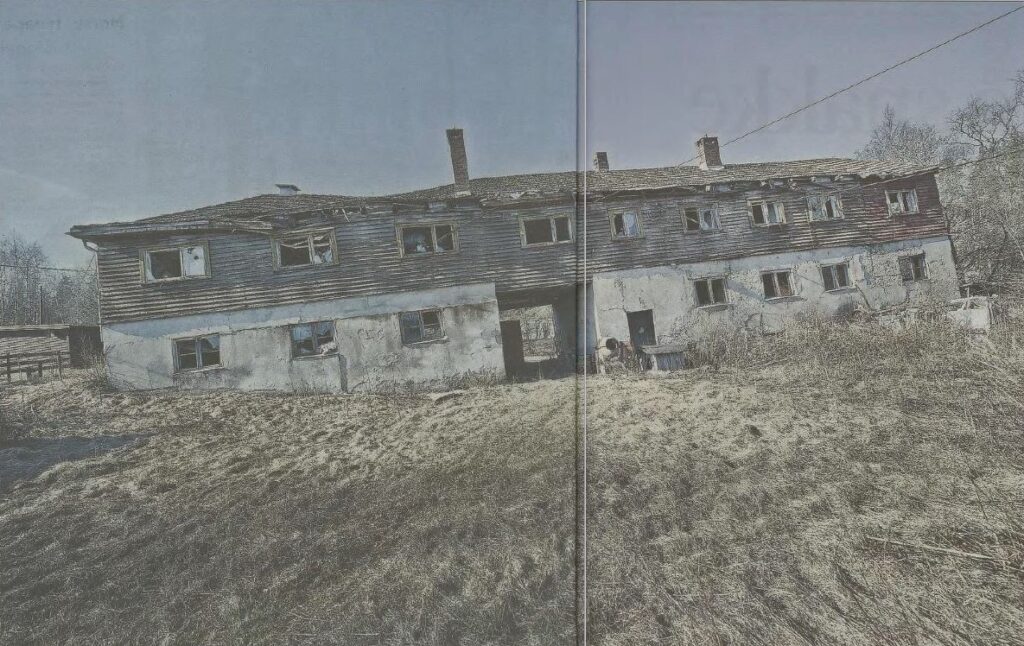

A few months later, on 12 April 1950, they could, however, confirm that, yes, a fountain pen factory was actually going to start up in Ski, more precisely in Siggerudgrenda in Vellumstadvika. The building was built by farmer Arne Karlsrud, and was to contain a general store, cafe and various small industries. Karlsrud told Østlandets Blad that he had hired out some premises to an “Oslo man who has started – as far as I know – the country’s only factory for fully manufactured fountain pens. They are not the usual ballpoint pens that it is supposed to be a lot of already, but real quality pens of the kind we have imported from abroad in the past”.

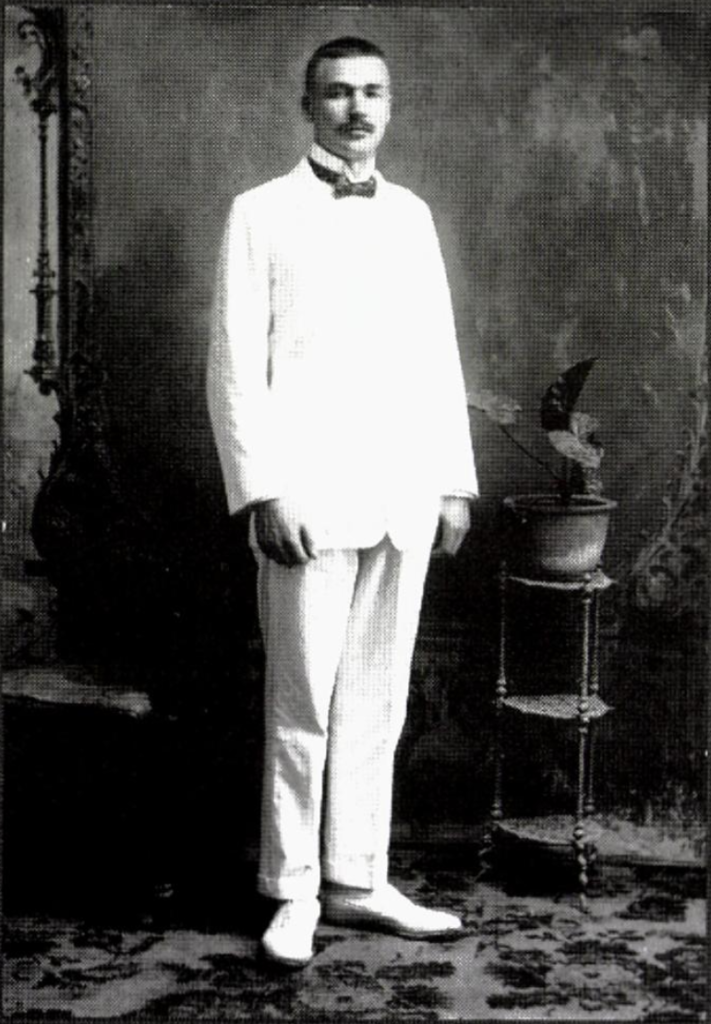

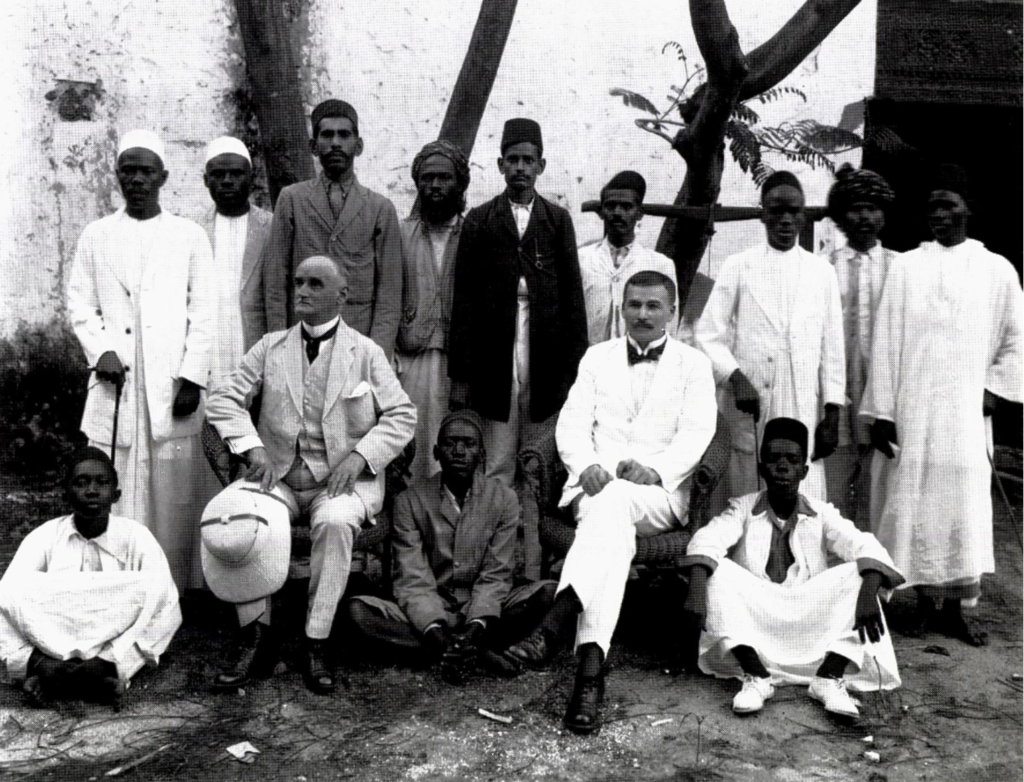

The Oslo man Karlsrud was talking about was Jens Kristian Hejer. Hejer was born in 1886, and originally came from Idd, which today is part of Halden county. However, he spent almost his entire adult life abroad. In 1920 he was employed by Norway East Africa Trading Co. (NEAT), and was appointed Norwegian consul in Zanzibar.

He held this position for three years, before he left Africa in August 1923. He had got a new job as director of the newly started factory of O. Mustad & Søn in Karlovac, Yugoslavia (today’s Croatia).

He remained in Yugoslavia for many years. In 1935, the Norwegian authorities established a vice consulate in Karlovac, and Kristian Hejer again received a consul post. In 1937 he was awarded the Yugoslav Order of St. Sava IV class for his efforts. In 1947, the factory in Karlovac was nationalised, and Hejer then took his family back to Norway.

Two years later, on 22 November 1949, he registered Dorn Fyllepennfabrikk A/S in the Norwegian trade register.

The company had its head office in Oslo, but the factory itself was established in the spring of 1950 in this new premises in Siggerud at Ski. It was expensive to build industrial areas in Oslo, and many companies set up commercial offices in the capital, but left their factory operations outside the city. It was in connection with this that Arne Karlsrud saw an opportunity, and set up an industrial building on his land, where Dorn and several other small companies rented premises for their operations.

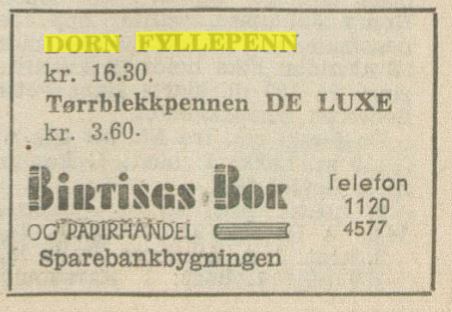

Dorn was an ambitious company, and set the goal of producing 100,000 pens and mechanical pencils a year. They were supposed to be affordable pens for regular people, and the first pens that were produced sold for NOK 16-20 per piece. The machines at the factory were initially borrowed or rented from Sweden, but probably bought up by the factory eventually.

The factory had several connections to Sweden that are a bit difficult to untangle. Those who worked at the factory referred to many of the parts they assembled in Swedish terms (they called the rubber sacs “blåsor”, among other things, although these are usually referred to as “gummislanger” in Norwegian), and the factory initially had a young, Swedish foreman called Göran Nilsson.

There were several attempts to start fountain pen production in Sweden in the 1940s. The first of the Swedish factories is said to have been Aktiebolaget Stockholm’s Reservoarpennfabrik in 1944, which had a close collaboration with the better-known Danish Penol factory. There was also a factory in Strømstad in the late 1940s, which went bankrupt (both machines and some personnel from this factory ended up in the early 1950s at Arnold Wiig’s factories in Idd, the same place Kristian Hejer came from).

The fountain pen industry in Norway was relatively new when Dorn started. Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk had been around for a while, but in the 1930s and 1940s the lion’s share of their pens were most likely still manufactured in Germany, and only assembled in Norway. It was probably natural for Dorn to get help and expertise from Sweden, which had been fabricating fountain pens for some time already.

The factory had 10 workers, who in the autumn of 1950 applied to organize themselves through the Ski and surrounding iron and metal workers association. They were refused, and sent on to the Norwegian Chemical Industry Workers’ Union, as they mostly worked with plastic materials. It is not known what the result was with this union, but one can imagine that it was not easy to know which union was the best fit for the fountain pen workers. This was a new industry in this country.

The company changed its name to College Fyllepennfabrikk A/S in December 1952, although by this time they had been calling the pens “College” for some time already. Jens Kristian Hejer was still the sole manager, but only a month later, on 2 January 1953, he died.

However, the death of the factory owner was not the end of the factory and pen production. On 22 April 1953, there was an advertisement in Aftenposten about a fountain pen factory that was for sale. The contact address given was Akersgata 16 in Oslo, which was the same address as the business office of the factory.

It seems that they managed to find new owners, because after an extraordinary general meeting on 7 July of the same year, it was reported in Norsk Lysingsblad that the company’s chairman was now Ludvig Jonathan Beckman. Thor Beckman was given the company’s power of attorney, and several hints indicate that he was the one who took over as general manager.

Interestingly, Ludvig Beckman also originally came from Idd. I am unsure of the family relationship between Ludvig and Thor Beckman, but as far as I have been able to find out, Thor was born in 1928, so he may have been Ludvig’s son. They were both state authorized auditors. Ludvig had his own audit office in Oslo, and was, among other things, an auditor for the national newspaper Dagbladet. Thor later took over this job for Dagbladet, so there are several things here that indicate that he probably worked for the older Beckman.

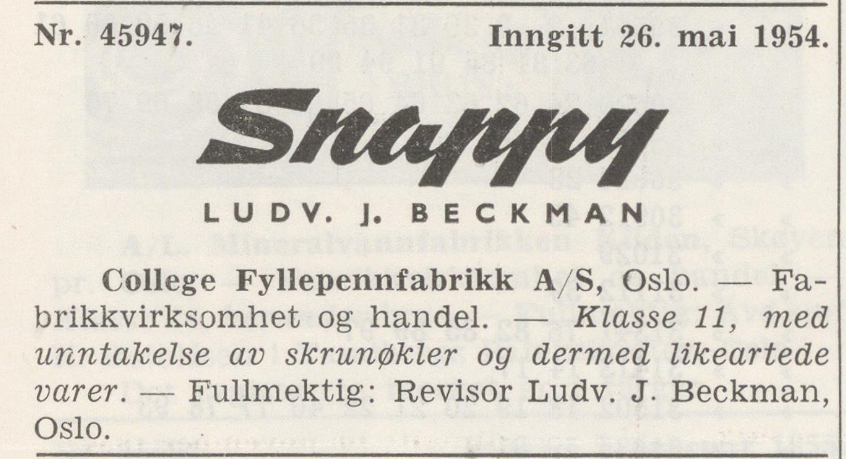

They took over the College fountain pen factory in 1953. What happened next is a bit vague, and I have only managed to find a few small hints here and there. On May 26, 1954, Ludvig Beckman took out a patent for something he called “Snappy” in connection with the fountain pen factory, but the small notice I have found about this in the Norwegian Journal for Industrial Legal Protection from 1955 does not say anything more about what this was for.

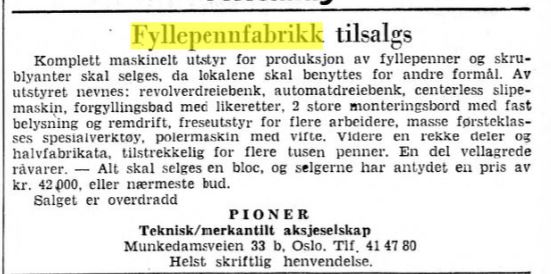

On 10 November 1954, there was an advertisement in Aftenposten about “Fountain pen factory for sale”. It said:

Fountain pen factory for sale: Complete mechanical equipment for the production of fountain pens and pencils is to be sold, as the premises are to be used for other purposes. The equipment includes: turret lathe, automatic lathe, centerless grinding machine, gilding bath with rectifiers, 2 large assembly tables with fixed lighting and belt drive, milling equipment for several workers, lots of first-class special tools, polishing machine with fan. Furthermore, a number of parts and semi-finished products, sufficient for several thousand pens. Some well-stored raw materials. Everything is to be sold en bloc, and the sellers have indicated a price of NOK. 42,000, or the nearest offer.

We are talking about a lot of equipment, and it’s clear that this must have been a factory of a certain size. The amount of equipment matches well with the number of employees we know College had. But we cannot know with 100 percent certainty that the ad applied to this factory. It may have been Arnold Wiig in Halden, who also stopped pen production around this time. There is little evidence that College continued to make pens after this, but the company continued to exist for quite some time.

In 1956, for example, we find an entry for College Fyllepennfabrikk in Norges Handelskalender, still with Thor Beckmann as manager and office at Akersgata 16.

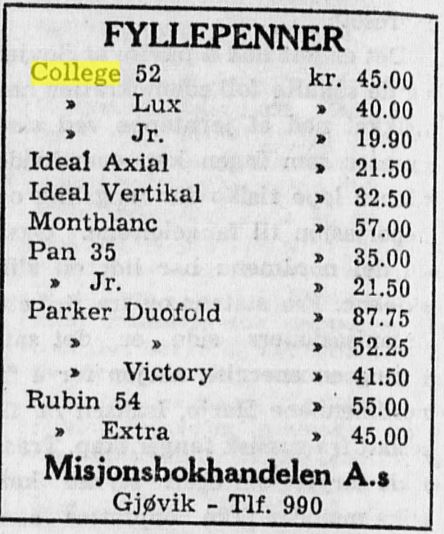

When you search for “College fountain pen” in newspaper archives and the like, you get quite a few hits in the mid-50s. Especially in 1954, it seems that these pens were popular prizes in raffle draws in various newspapers, and I have also found a price list from a book store in Gjøvik, which still had College pens in March 1955. After 1955, however, there’s not much more to find about this brand.

Nevertheless: we actually find an entry for College fountain pen factory in the Oslo address book as late as 1978. The address is then given as Munkedamsv. 3B. It is difficult to say for sure whether they were still active at this time. Definitely not as a factory, but maybe as importers of other pens.

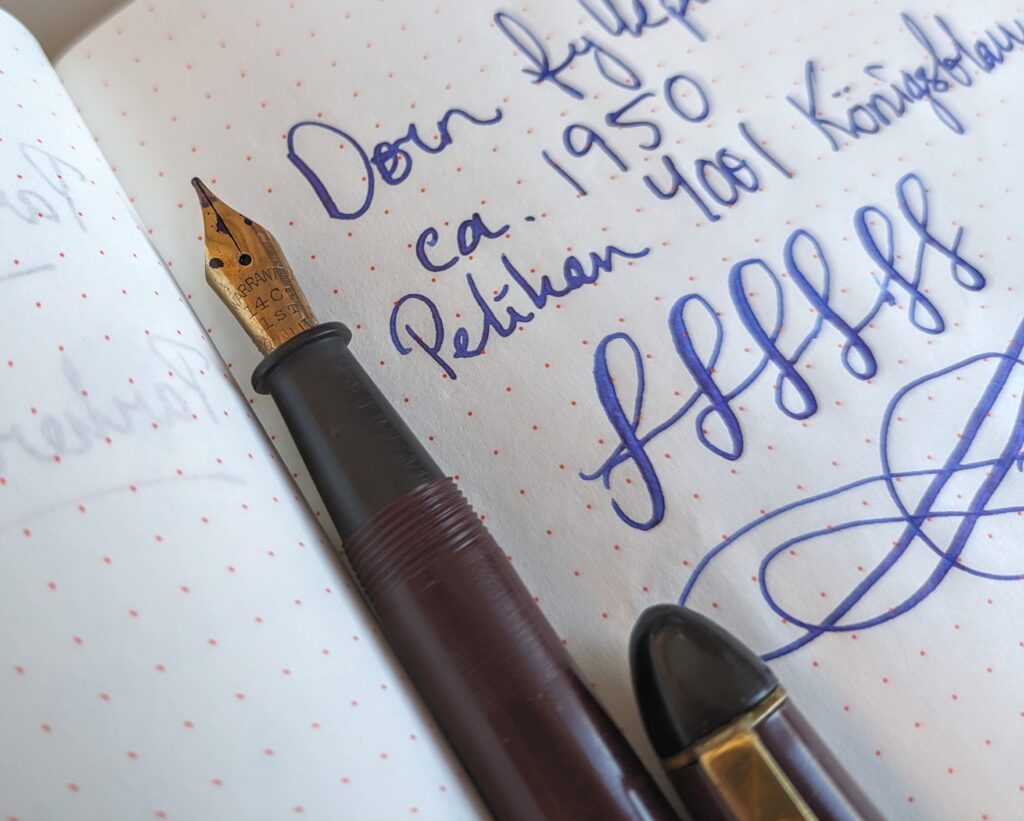

Considering how many pens they supposedly produced at this factory, it is surprisingly difficult to find Dorn or College pens today. It took me several years from the time I started looking for them until I was able to acquire a few, and today I have one Dorn pen and three College pens in my collection. It is natural to compare them with the Pan pens, which were also produced in Norway in the 50s.

It seems to me that the quality of the Pan pens was much higher than Dorn and College. The factory at Ski used materials that shrink over time. All the pens I have from Dorn and College bear the mark of this. The result is that you have pens where the caps just barely fit unto the pen, and the metal rings on the caps have loosened over the years because the material around them has shrunk.

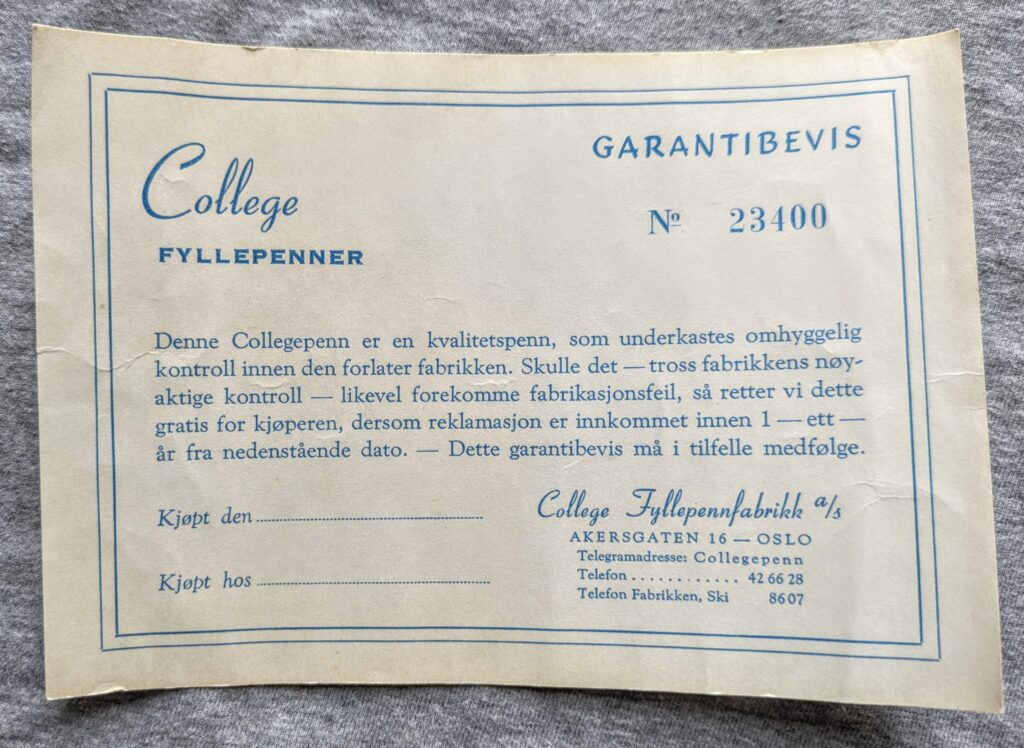

In other words, these pens have not stood the test of time as well as the Pan pens. It is also interesting to note that while the Pan pens was guaranteed against manufacturing defects for an indefinite period, the guarantee period for the College pens was only one year from the date of purchase.

I’ve restored two of my pens: a Dorn and a College Lux, and aside from the flaws described above, they’re both equipped with surprisingly good – and very flexible – nibs. There was absolutely nothing wrong with the writing properties of these pens, and back in the days you could buy them for relatively cheap compared to many other fountain pens on the market at the time. I am tempted to say that the two pens I have in writing condition from this factory have better writing characteristics than any of the Pan pens I have tried. And that speaks volumes, because the Pan pens are also very good to write with.

Sources

Some of the sources below are newspaper clippings I’ve had lying around for several years, and which I haven’t been able to find again online. I have linked to the sources I have been able to find.

The information about the Swedish supervisor and the use of the term (“blåsor”) came from a phone conversation I had a few years ago with Anne Marie Rønvik. Her mother worked in the factory, and she herself helped with simpler tasks now and then.

Morgenbladet, 17.06.1920 – «Utenriksvæsenet»

Morgenposten, 25.08.1923 – «Fra Statsraad igaar»

Den 17de Mai, 22.01.1935 – «Konsulata»

Vestopland, 14.10.1937 – «Ordensutnevnelse»

Norges Handelskalender, 1940 – «Jugoslavia»

Halden Arbeiderblad, 05.12.1949 – «Norske fyllepenner snart»

Østlandets Blad, 05.12.1949 – «New Deal-prinsippet tenkt anvendt i Ski»

Østlandets Blad, 12.04.1950 – «Norsk fyllepennfabrikk igang i Siggerudgrenda»

Fædrelandsvennen, 24.08.1950 – «Dorn fyllepenn»

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1950 – «Dorn Fyllepennfabrikk»

Aftenposten, 22.04.1953 – «Fyllepennfabrikk»

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1953 – «College Fyllepennfabrikk»

Aftenposten, 10.11.1954 – «Fyllepennfabrikk til salgs»

Oppland Arbeiderblad, 12.03.1955 – «Fyllepenner»

Norsk tidende for det industrielle rettsvern, 1955, vol. 45 – «Snappy»

Norges Handelskalender, 1956 – «College Fyllepennfabrikk»

Akers-posten, 28.11.1964 – «75 år»

Haldenbiografier 1, 1973 – «Kristian Hejer»

Hytta på Hvaler, 1977 – Picture of Thor Beckman

Nordmenn i Afrika, Kjerland/Bang, 2002 – «1920-årene: Kristian Hejer og Hans Severin Lund – siste år i Zanzibar»

Østlandets Blad, 12.04.2012 – «Riv skiten, ellers blir det dagbøter»

Østlandets Blad, 06.06.2012 – «Mamma jobbet på fyllepennfabrikken»

Nordicwomeninfilm.com – Article about Grethe Hejer, daughter of Kristian Hejer