Nibby Sunday – “There was buoyancy in him” – The Story of Eberhard Bredesen Oppi and The Norwegian Fountain Pen Factory

In the spring of 2018, I inherited a pair of Pan pens, and started looking for information about this Norwegian fountain pen brand. At first it was difficult to find any reliable information, but as I managed to uncover little hints here and there, those hints could be used to dig deeper. I have written about Pan and Eberhard Bredesen Oppi several times in the past, and the most recent example up until now is an article in Norwegian from May 2020.

Since then, I have worked hard to learn as much as possible. There were a lot of questions about this brand that were unanswered. Pan and Eberh. B. Oppi is in many ways the reason why I have also written several articles on the Norwegian version of this blog about other Norwegian pen brands. It is through the research about Pan that I have stumbled upon other sources about Norwegian pen production, and this is work that has followed me through almost my entire time as a fountain pen enthusiast and pen blogger. Ultimately, all of my historical posts on Pennen er Mektigere can be traced back to the desire to find out more about the Pan pens.

Therefore, it is extra nice to be able to present what has become the most comprehensive article on the blog up to now. This is the culmination of over five years of research work. I have no illusions that I have finished this work yet, and I still have unanswered questions about the Pan pens, but it was time to write an updated article about this important Norwegian pen brand, which has come to light again through the past few years, and gained higher and higher esteem in the Norwegian fountain pen community.

“There was buoyancy in him”

The story of Eberh. B. Oppi Kunstforlag and Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk is a success story about a family owned company that lasted through almost the entire twentieth century. It is the story of a fountain pen factory that managed to adapt to major changes in the market, and which flourished at a time when a majority of other companies in the same industry went under. It is, however, also a tragic family story. In this article, we will look into the German fountain pen Mecca: the city of Heidelberg, we will go to a bombed-out Åndalsnes in the spring of 1940, we will climb the Norwegian mountains, and travel into Norwegian classrooms. It’s a long and fascinating story, and it all started with a barbershop in the capital city.

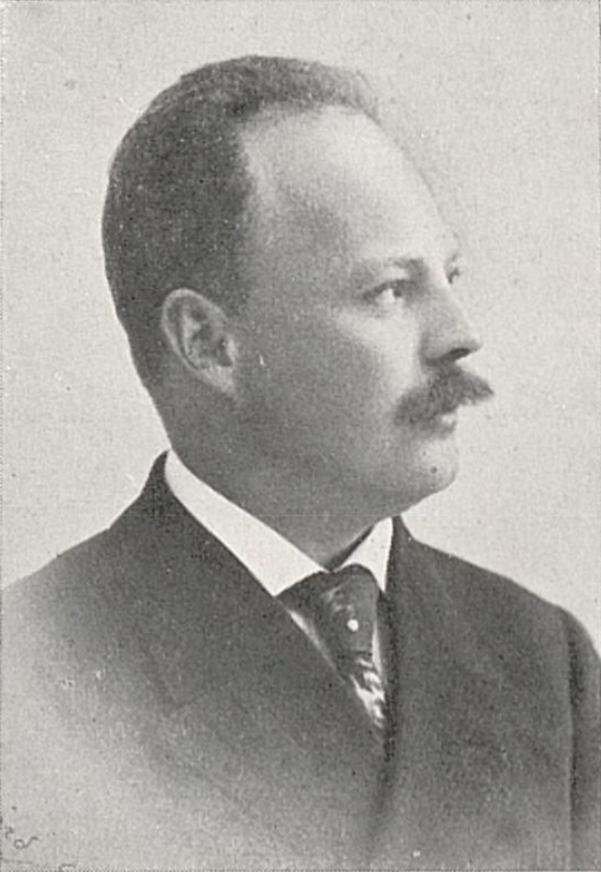

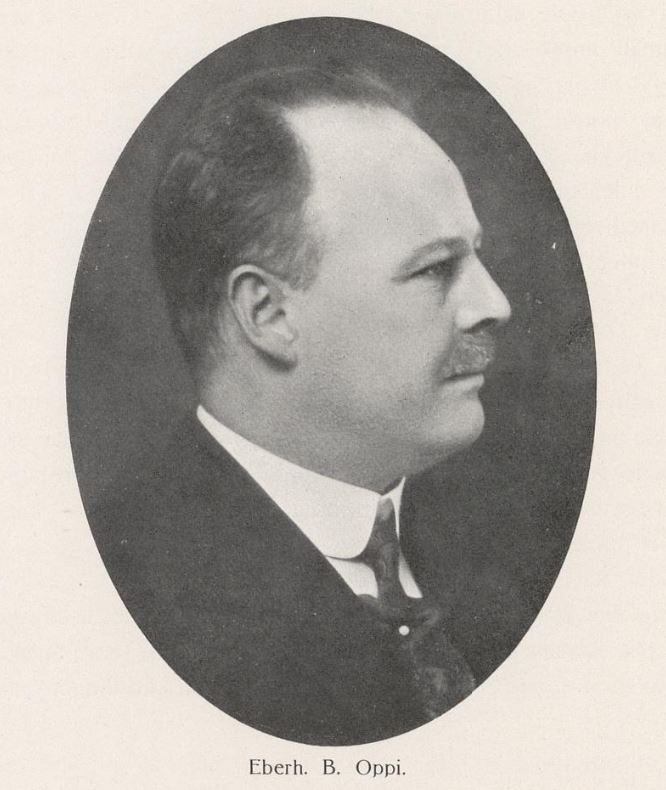

Eberhard Bredesen Oppi was born in 1878 on the Oppi farm, in Hof in Solør. He went to Oslo (then Kristiania) as a 14-year-old and became a barber’s apprentice. He was still only a teenager when in 1896 he opened his own barbershop at Bogstadveien 25 in Kristiania.

One of his neighbors in Bogstadveien 25 later described him as “small, lively, full of energy and with many ideas and plans. There was buoyancy in him”.

He married Inga Hansen, and the two had a daughter, Hjørdis Marina, in 1899. The couple had their second daughter, Ebba, in 1901.

In 1902, Oppi reported to the Oslo Trade Register that he, under the firm “Eberh. B. Oppi”, intended to trade in Kristiania. He still had the barbershop, but in a shop next door to the salon, he now started selling cigars and alcohol. It is possible that the cigar shop was first owned by Inga, who had her own company together with Eberhard’s older brother, Martin, but it is quite obvious that the couple worked together in both enterprises.

The winter of 1905 was rough for Eberhard Oppi. On February 15, his daughter Hjørdis died of heart failure, just five and a half years old. Barely one month later, on March 12, his wife, Inga, also died, after a long illness. She was 31 years old.

Nordisk Kortforlag

Eberhard Oppi started a publishing business in addition to his two other businesses. It may have been as early as 1901, but in 1907 he was at least well underway, and this year he established the company Nordisk Kortforlag (Nordic Card Publisher), which specialized in postcards.

He bought up the estate of Petter Alstrup’s Kunstforlag after they went bankrupt in 1907, and resold the goods through his own publishing house. He did something similar with Abels Kunstforlag a few years later, in 1919. With this, he also gained the rights to print a large number of paintings by well-known Norwegian artists.

In 1909, the widower Eberhard remarried, to Olga Agnete Jensen Bjerte. She adopted his daughter, Ebba, and they had two sons together: Bjørn Conrad (1910) and Per Eberhard (1918).

The publishing house moved from Bogstadveien in 1910 to Rådhusgata 16. However, Oppi kept the premises in Bogstadveien for a while, and continued to run a cigar shop there for a few years. It is unclear how long he operated the salon and cigar shop. In 1915 it is stated that he was still importing cigars at Bogstadveien 25, but after that the references to this business stop. In 1927, there was still both a barbershop and a tobacco shop at Bogstadveien 25, as the picture below shows. Whether Oppi still owned them, or whether they were continued by new owners, is not known.

The building in Bogstadveien 25 still stands today. The premises that were once a hairdresser and barber are now home to the handbag brand Moo. The premises of the cigar shop are today a Traktøren store, which sells kitchen equipment, and the first premises of the art publisher around the corner in Vibes gate are today used by the clothing and design store byTiMo .

“New and modern premises”

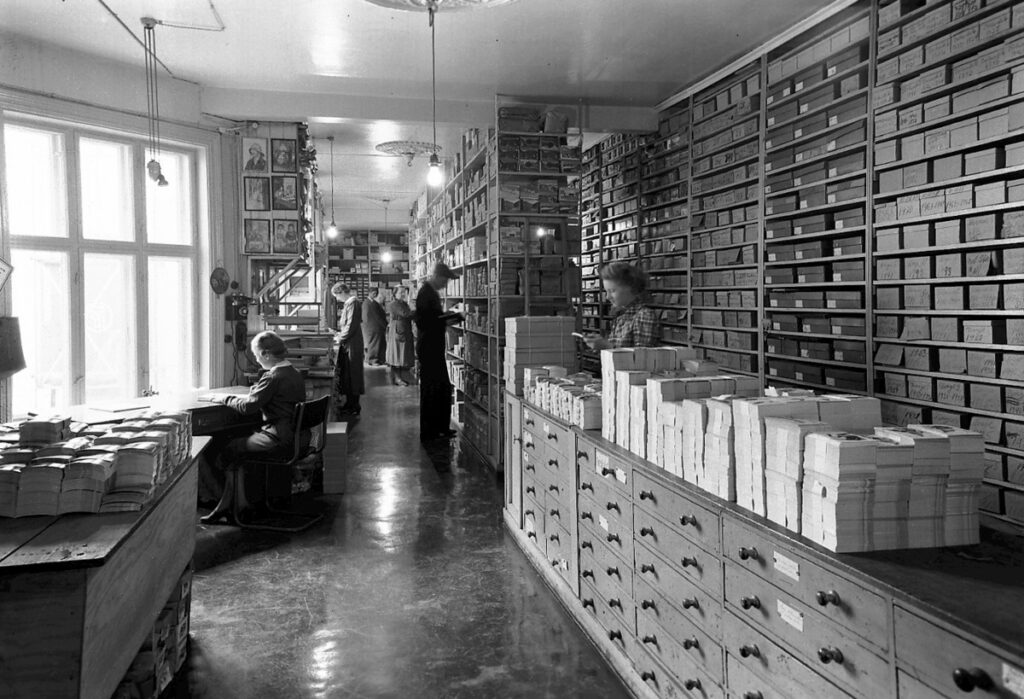

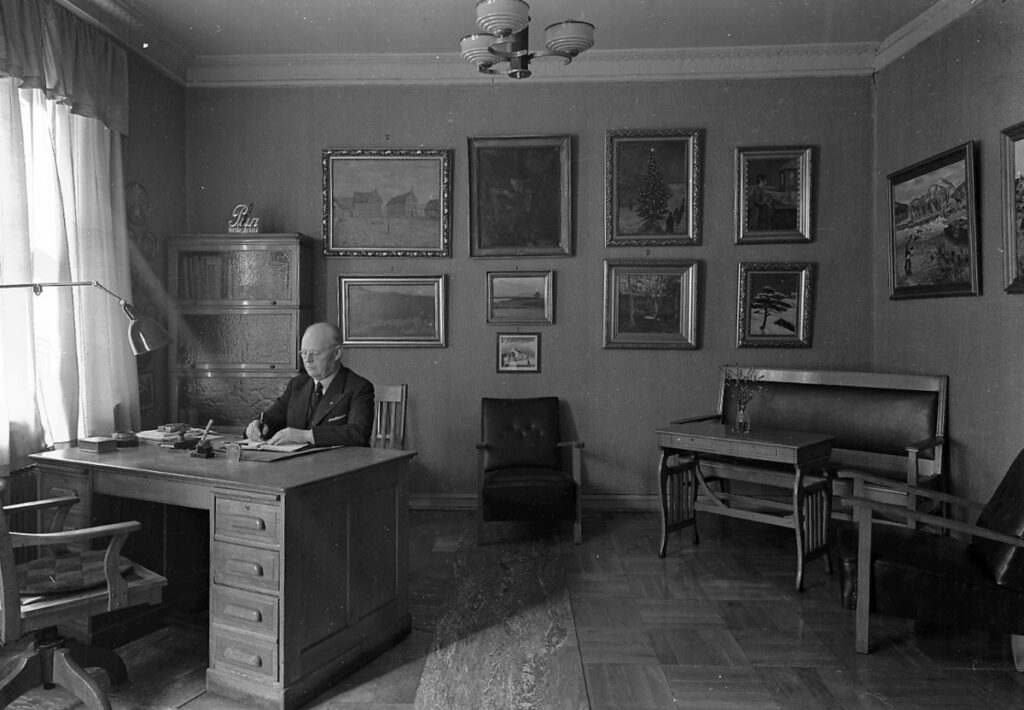

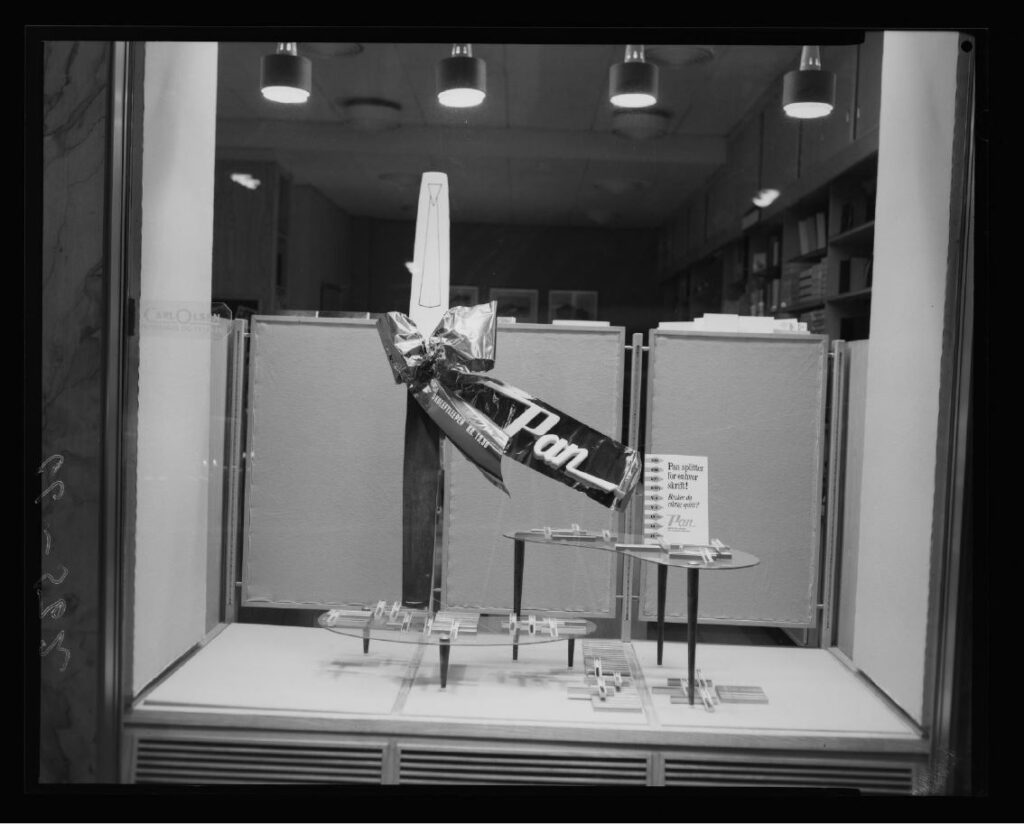

Oppi built up his publishing business in Rådhusgata 16, and grew quickly. They had their own platinum facility for the production of postcards, was rewarded with gold medals and prizes at several major exhibitions, and was already in 1915 referred to as “one of the largest art publishers in the country”. It did not take many years before the premises in Rådhusgata became too small. In 1917 they moved again, this time into a large building of around a thousand square meters in Keysers gate 5. Here they were to remain throughout the rest of the company’s long life. Oppi announced in the newspaper Tidens Tegn on March 7, 1917 that “My office, warehouse and printing house have now moved to large, new and modern premises in my own building”. The wording indicate that Oppi had bought the property in advance of the move. The building in Keysers gate 5 is still referred to as “Oppi-gården” today.

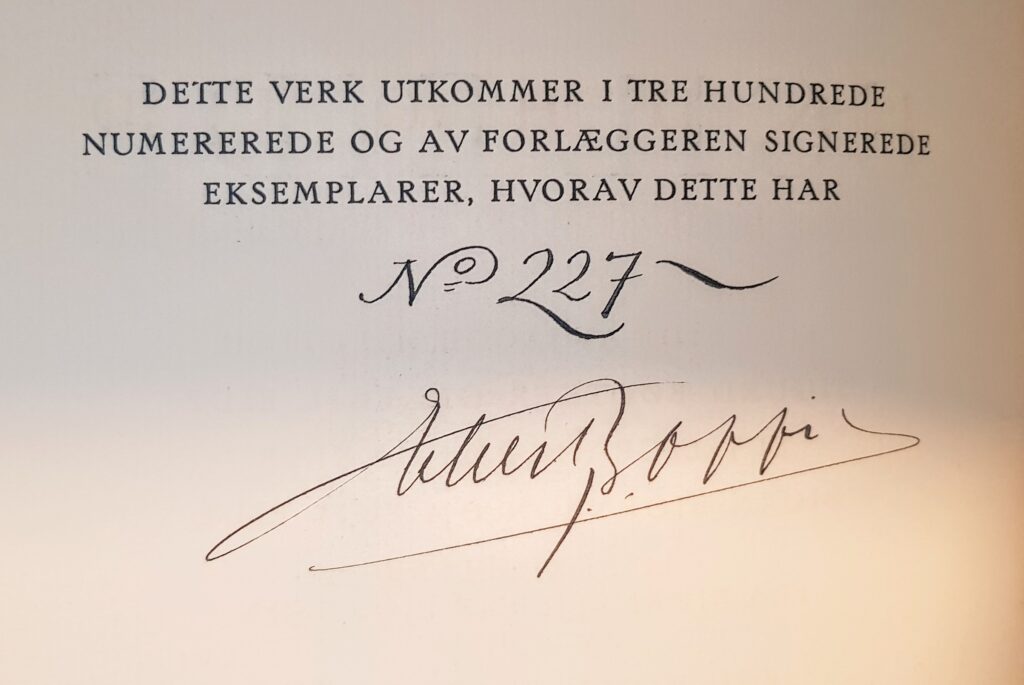

The Oppi publishing house was best known for its postcards to begin with, but they also published a number of books. Oftentimes, books with art prints and rich illustrations. In 1921, they published the two-volume work “Norges Musikhistorie” (Norway’s music history), which was the first time anyone attempted to collect the entire history of Norwegian music in one work. The two volumes were rich in illustrations, had pictures of the various composers, and lots of sheet music examples. The reviewers were ecstatic when they hit the shelves, and claimed it was a literary event without parallel in Norwegian literature.

Another major publication was architect Holger Sinding-Larsen’s magnificent work on the history and architecture of Akershus Fortress, which was published in 1924 as a result of a archaeological investigation of the fortress complex in the period 1905-1924. They also published the annual Christmas magazine “Juleglæde” for many years (from 1911 onwards), and another annual publication with pictures, called “Norwegian nature”, which was also published in English, and helped to build up the Norwegian tourism industry.

Oppi was also an active philanthropist. In the 20s, he was vice-chairman of the Norwegian Association for the Promotion of Care for Children, which, among other things, ran a home for blind children in Jessheim. He was also chairman of Oslo Rotary Club’s children’s committee, and vice-chairman of the Norwegian Society for Music Research. In addition to that, he was active in the masonic lodge Den Norske Storloge Polarstjernen, and held board positions in several companies. In the 1930s, Oppi also sat on the boards of the Art Publishers’ Association and the National Association of Retail Wholesalers.

On top of this, from 1924 he was vice consul for Latvia in Norway, and in 1930 he became consul. As thanks for his efforts in the consular service, he was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Three Stars of Latvia. To say that Eberhard Bredesen Oppi was a versatile man with lots of iron in the fire would be an understatement. And soon he was to start yet another enterprise: he was about to go into the fountain pen industry.

Pan

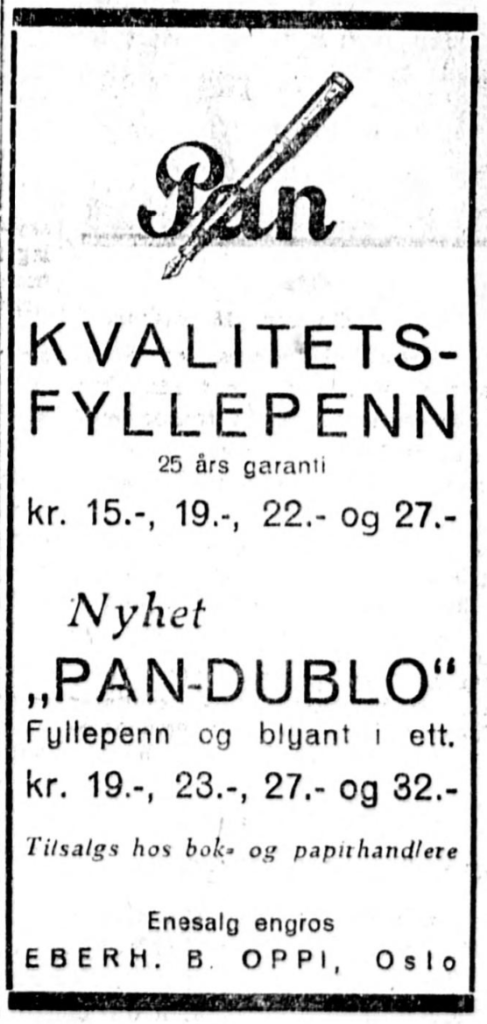

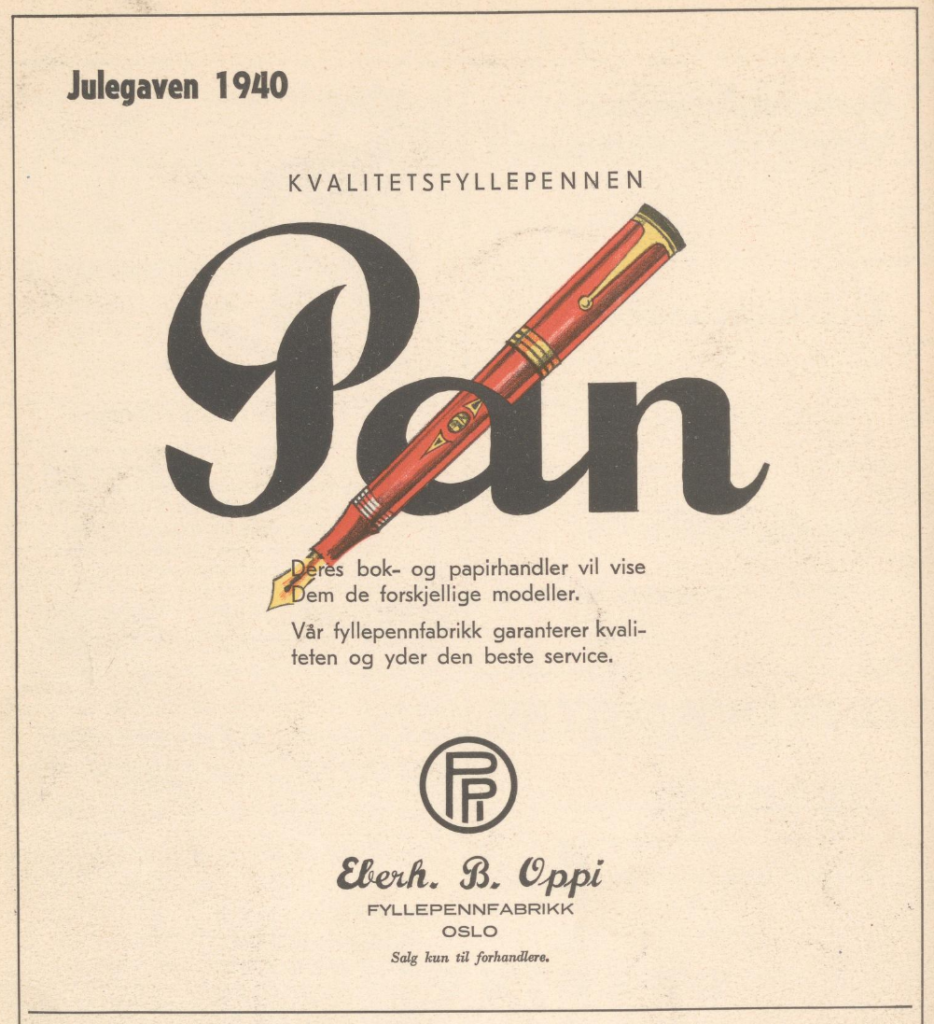

The first newspaper advertisement for Pan pens in Norway was printed in the autumn of 1931, and was an advertisement for Pan-Dublo, a fountain pen and mechanical pencil in one. You could also buy more ordinary fountain pens, and both the ordinary fountain pen and the Dublo came in several editions in different price ranges. The pens were imported from Germany by Eberh. B. Oppi, and was produced at a pen factory in Mannheim called Oberrheinische Federhalterfabrik Zahn, Leser & Co.

It is not so easy to find information about Zahn, Leser & Co., but I have been in contact with Thomas Neureither who runs the Füllhaltermuseum Handschuhsheim, a fountain pen museum in Heidelberg, Germany. He has a lot of knowledge about the pen industry in the city.

In 1883, Heidelberger Federhalterfabrik started production, and six years later this factory was taken over by Heinrich Koch and Rudolf Weber, under the name “Koch, Weber & Co”, or KaWeCo. The factory grew steadily over the next decades, and in 1921 they had 600 employees. Among those who worked at Kaweco, several eventually broke away and started their own fountain pen factories in the Heidelberg area. Brands such as Osmia, Hermann Böhler, Luxor, Mercedes Pens, Orthos, Lamy, as well as nib manufacturers such as Bock and Rupp were all established in or around Heidelberg, primarily by people who had learned the business through working at Kaweco. It is believed that the Heidelberg area has had around 40 different fountain pen and nib factories from 1900 until today, and that is in a relatively small city which today has a population of around 160 000 people. It is safe to say that Heidelberg was a center of power for fountain pen production in Europe throughout most of the 20th century. Today, Lamy and Bock are still based in the city.

Heidelberg is only around 20 km from Mannheim, where Zahn, Leser & Co. started in the 1920s. It is therefore natural to count them as part of the “Heidelberg cluster” of pen factories.

The earliest reference we have been able to find for Pan pens specifically, is a German advertisement from 1930. In the advertisement, Zahn, Leser & Co. states, among other things, that they have a good offer for companies interested in buying black fountain pens in hard rubber for resale. It is likely that Oppi came across a similar advertisement from them, and started a collaboration to introduce affordable fountain pens of good quality to Norway. He probably saw that there could be a market for fountain pens at a slightly lower price than the more expensive Parker pens that were very popular at the time, and especially if they could eventually be marketed as “Norwegian”.

The pan name

So where did the name Pan come from? This is a question that both Thomas Neureither and I have thought about a lot, and discussed a bit back and forth. It is unlikely to be based on an abbreviation. If so, what would it have been short for? If Zahn, Leser & Co. were to use an abbreviation, it would likely have been something along the lines of ZaLeCo (to follow Kaweco’s example).

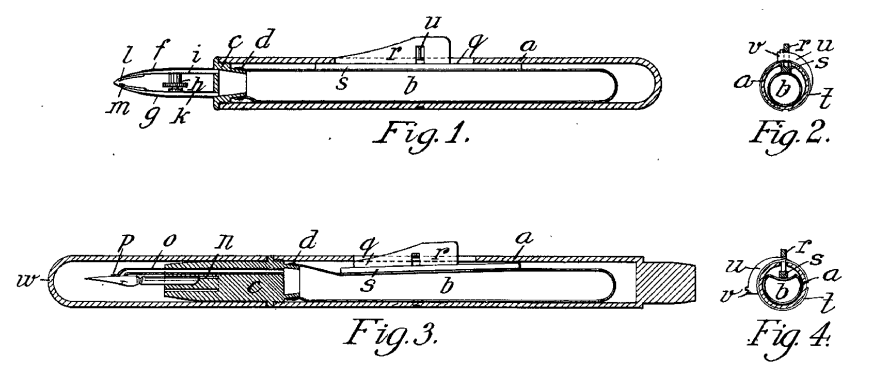

One possible source for the name, although perhaps unlikely, is the engineer Georg Pan, who lived in Hamburg in the early 20th century. In 1903 he registered a patent for a new type of fountain pen. Apart from the name, however, there is no connection to be found between Georg Pan and the fountain pen factory in Mannheim, and the pen he patented bore very little resemblance to the pens of the same name that came almost thirty years later.

Many pen manufacturers took names inspired by the countries they produced pens for. The Heidelberg factory Hebborn, as an example, made pens under the brands Luxor and Big Ben, which were primarily sold in the UK market. With this in mind: could the name have been inspired by the book of the same name by Knut Hamsun? Personally, I don’t really think so. The Pan pens were also sold in Germany. Originally, they were not made specifically for the Norwegian market. And if they had wanted to give the pen a “Norwegian” name, I imagine they would not have chosen Pan, but rather something more Norwegian og Norse, such as Troll, Viking, Bifrost, or the like.

Maybe it was Pan, as in Pandemonium or Panorama? From the middle of the 19th century and through the next hundred years, there was a flurry of new words in the English language that used pan- as a prefix to indicate that the word applied to everything or everyone. To name a couple of concrete examples: the supercontinent Pangea, which existed some 2-300 million years ago, was named in 1920, and Pan American Airways was founded in 1927, just a few years before the first Pan pens hit the market. Pan was in many ways a buzzword in the 1920s and 30s.

Pan is originally a Greek word/name. In Greek mythology, Pan was the god of nature, shepherds, passion, music (the pan flute is named after him), and the pastoral, and he was a companion of the nymphs. He is usually depicted as a faun. Greek mythology had something of a revival in the late 1800s and early 1900s. You can see it well in the visual arts and in the Art Nouveau movement, which drew a lot of inspiration from there, and not least in the music of Claude Debussy (“Afternoon of a Faun” and “Syrinx” are good examples of Debussy pieces inspired directly by the myths about Pan). You can also see it in the literature. Pan appears in many well-known books from this period. Peter Pan is obviously named after him, we meet him in a chapter in “The Wind in the Willows” by Kenneth Grahame, and he also inspired Hamsun’s book from 1894.

It is safe to say that Pan, both the Greek god and as a prefix, was a fashionable word in the early 20th century, and maybe Zahn, Leser & Co. simply chose a brand name that was popular and trendy then and there. And maybe the name of the Greek god of passion, could ignite a passion for writing as well?

The Norwegian Fountain Pen Factory

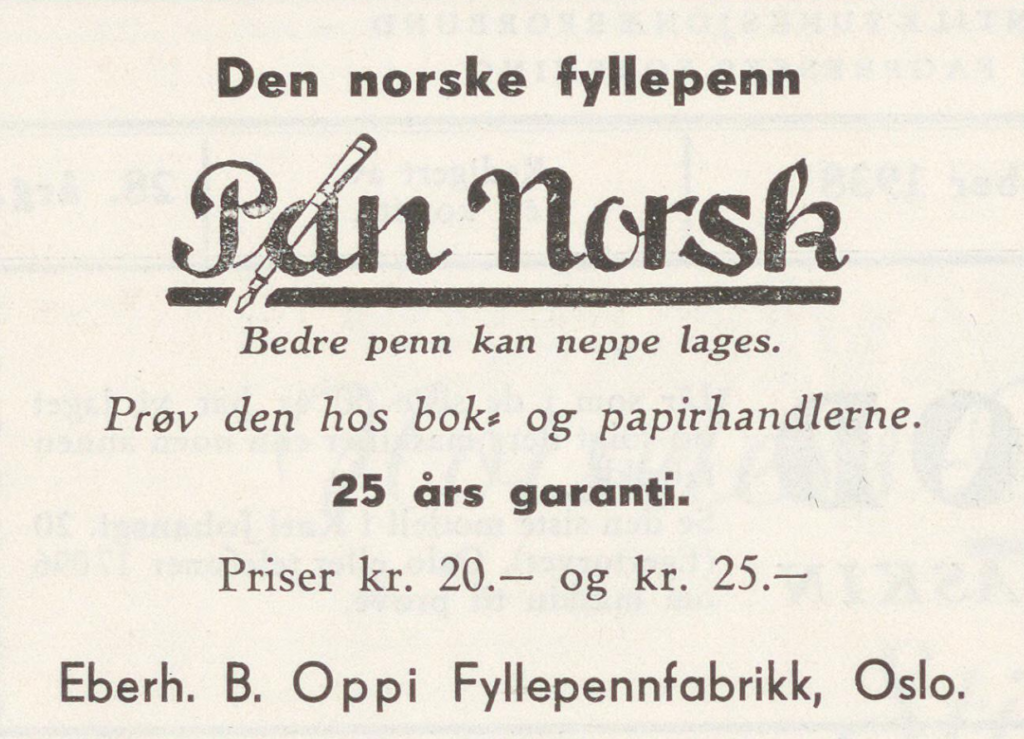

It is a bit uncertain exactly when Oppi started manufacturing Pan pens himself. As early as 1934, there is an entry for “Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk” (The Norwegian Fountain Pen Factory) at Eberh. B. Oppi in the Oslo address book, but the factory was not entered in the trade register until January 1940. In 1938, the first advertisements appeared with the designation “Pan Norsk” (Pan Norwegian), which may indicate that at least parts of the pen were made or assembled in Norway, or at least was made specifically for the Norwegian market.

In any case, it is clear that the Pan pens started out as a purely imported product from Germany, but that Oppi had the opportunity to adapt them quite early on, or special order pens that were unique to the Norwegian market. You find Pan pens relatively early in the 1930s with Oppi’s own logo, for example. The Pan pens were also sold in Germany, but it seems that most of those sold on the German market were piston fillers, while the Norwegian pens were mainly push button fillers. It can probably be imagined that there was a gradual build-up of the fountain pen factory in Oslo, and that they did not go from importing to making everything themselves overnight. One can also imagine that there was an idea to create a kind of Norwegian branch of the German Pan factory, but this collaboration probably fell apart during the war, for several reasons.

1940

The spring of 1940 was dramatic for Norway, but also for the Oppi company.

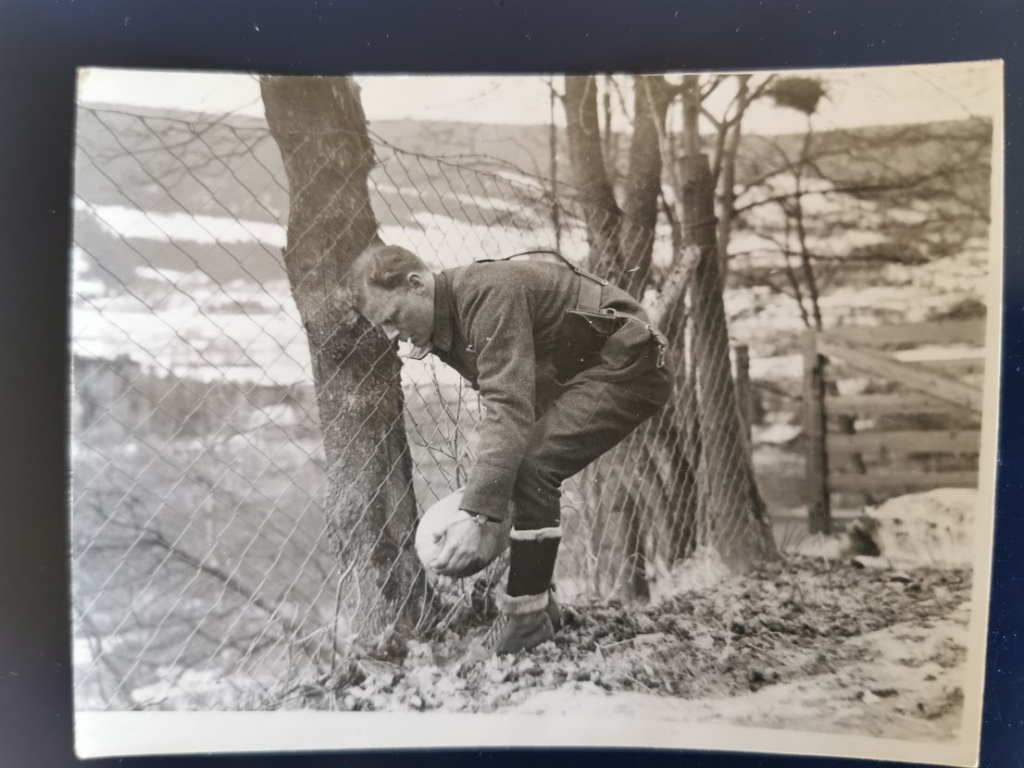

Bjørn Oppi, Eberhard’s oldest son, had worked for a while as a photographer for the art publisher, and was likely to be the one to take over the management of the company as his father grew older. During the outbreak of the war, the then 30-year-old Bjørn served in Åndalsnes, a small town on the west coast of Norway.

A lot happened in Åndalsnes in the second half of April 1940. The British landed a total of 7,000 soldiers there in an attempt to respond to the German invasion of Norway. On April 18, representatives from the Norwegian government arrived there and quickly established that it was too risky for the king and the rest of the government to travel via the small town as they fled from the advancing German forces (they went to Molde instead). The transport of the Norwegian gold reserve arrived in Åndalsnes on April 25, and loaded parts of the national treasury onboard British ships under constant bombardment from German planes, before they had to rush the rest of the gold on to Molde. The Germans bombarded Åndalsnes daily from April 20, until the beginning of May. At the end of April, the whole of Åndalsnes burned, and in the end only the station building was still intact. The British evacuated their soldiers again at the turn of the month, and the Germans marched in on May 2 and 3. In the middle of this chaos, Bjørn Oppi found himself, as a sergeant for the Supply Corps, Car Company 7.

Oppi was directing traffic at a crossroads outside Åfarnes in Veøy on April 30, during the British retreat, when he was hit by an unknown truck at high speed. The truck continued its journey without slowing down and was never found. Oppi died instantly.

The newspaper Vestfold wrote on May 22, 1940: “Oppi was in the automobile corps and had done excellent work during the English retreat to Åndalsnes. On April 30 there was panic and confusion. Oppi then tried to establish orderly traffic, but was run over and killed. It was only a few hours before his father died.”

The following day, May 1, Eberhard himself died, aged 62, of a heart attack. It is not known whether he managed to get the message about his son’s death before he himself passed away, and whether this news may have been a contributing factor. There are a few hints here and there which suggest that it may have taken some time before the family learned of Bjørn’s fate. One is the father’s obituary, which was printed in Aftenposten on May 6, where Bjørn is listed as one of the next of kin, together with his mother and two siblings, a whole week after he himself died. The second is that no Norwegian newspapers wrote about Bjørn’s death until the end of May. It is not hard to imagine that all the chaos in connection with the German invasion meant that it took some time for the news of his death to reach both the family and the press. He was first laid in a boathouse right next to where the accident had happened, and a few days later buried in Eid cemetery. Almost a month later, on May 25, he was brought to Oslo, and buried again, at Vestre Gravlund. It was only in connection with this that his death was reported in the media.

Bjørn’s wife, Gerd Brath, had recently lost her brother in combat near Stavanger. Now her husband was also dead. The Oppi art publishing house was now without both the man who had built up the entire company, and the man who was intended to inherit it.

The 1940s were dramatic for others than just Eberh. B. Oppi. The British bombed Mannheim several times during the war, but what was perhaps the biggest raid occurred on September 5 and 6, 1943. Large parts of the city were left in ruins. In the autumn of 1943 it was also reported that the fountain pen factory of Zahn, Leser & Co. was out of service. The factory was located in one of the districts that was hit hard during the bomb attacks at the beginning of September, so one can probably assume that it was damaged in these attacks, although we have no concrete sources to confirm this. In any case, the fact is that operations ceased in the autumn of 1943, and the factory was not resurrected again until 1947, in Heidelberg.

Karl Thorbjørn Naug

Karl Thorbjørn Naug was a non-commissioned officer in the army, and had both the Army’s shooting medal and the sports badge in gold. He was also a “treasured caricaturist during the weapons exercises”. In addition to the military, he graduated from Otto Treider’s one-year business school in 1920, and was a writer (he published at least two books), in addition to teaching shorthand. From the early 1920s he was the office manager at Eberh. B. Oppi Kunstforlag. Naug also designed several postcards for Oppi, and was eventually to become a central figure in the business together with the Oppi family.

Eberhard’s widow, Olga Oppi, took over as owner and chairman of the publishing house and pen factory. At the same time, Karl Thorbjørn Naug gained a more important role in the day-to-day operations, and joined the board of the company.

From May 1941, the board of Eberh. B. Oppi consisted of Olga Oppi, who was chairman, Ebba Oppi, Per Oppi and Karl Thorbjørn Naug. In 1943, Naug was arrested by the Germans, and spent the rest of the war in various German prison camps. The publishing house, which only three years earlier had lost both the founder and the eldest of the heirs literally overnight, was now also without another central figure. Considering the fate that awaited many of those captured by the Germans, it cannot have been obvious that Naug would ever return. It must have been tough for those who remained to run the business over the next few years. Fortunately, Naug survived his imprisonment, and returned to Norway in June 1945.

Per Oppi

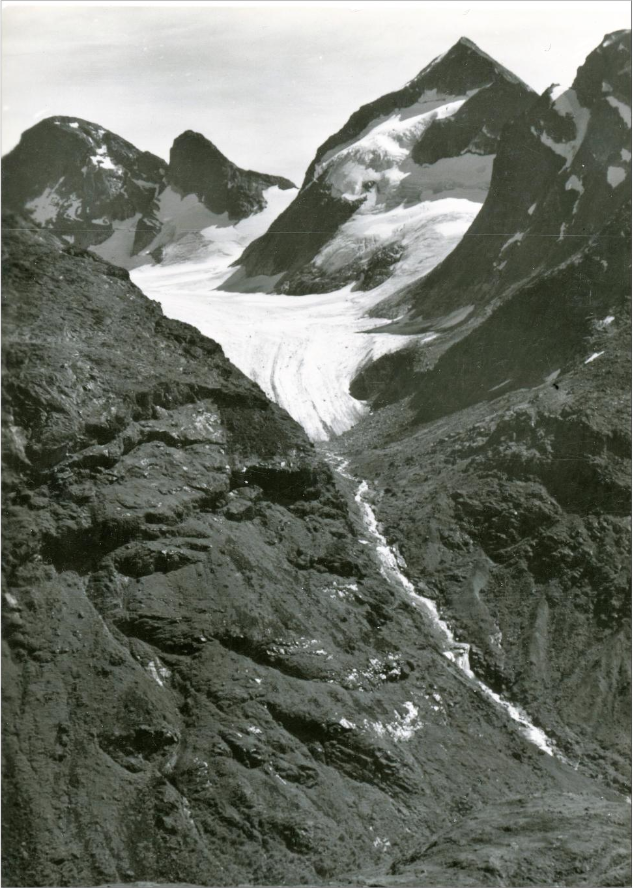

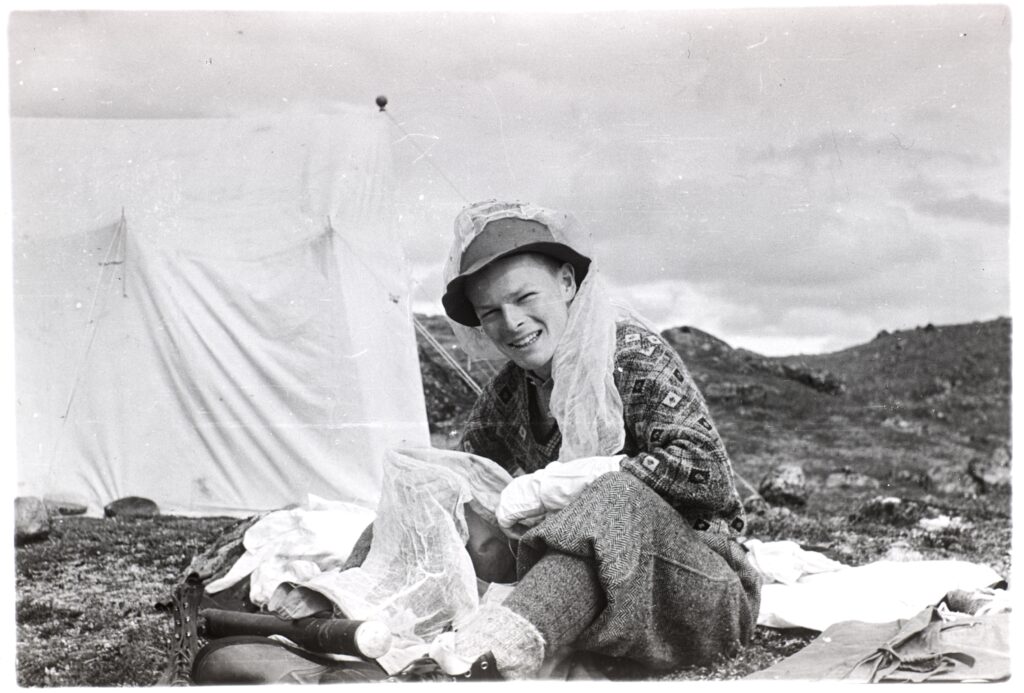

Per Oppi, Eberhard’s youngest son, was 22 years old at the outbreak of war. He was an active photographer, and became head of the photography department at the publishing house. In 1941 he won several prizes in the annual competition of the Oslo Camera Club and was also one of the people who started the color photography group in the club in the winter of 1942.

In addition to being a photographer, Per was a keen mountaineer. He took many pictures in the Norwegian mountains which ended up as postcards in the art publishing house. He was referred to as an exceptionally skilled photographer, and had illustrations in the yearbooks of the Norwegian Tourist Association, and for Norsk Tindeklub’s (the Norwegian mountaineering club) anniversary publication, “Norsk Fjellsport”.

In December 1947, Per was engaged to Else Færden, and the two were married on May 21, 1948. Two months after the wedding, Per and Else were at Gjendebu in Jotunheimen. Here he joined up with three other mountain climbers as a photographer for an ascent of the peak Knutholstind, south-east in Jotunheimen. The climbing team consisted of Otto Lundh, Botolf Botolfsen, Anton Heyerdahl jr. and Per Oppi. The plan was that Lundh and Botolfsen would follow an established route up to the top, while Heyerdahl and Oppi would take a route that had never been climbed before.

When Lundh and Botolfsen got to the top, they saw nothing of their friends. They went over the top to look for them, and on the glacier 150 meters below they spotted the lifeless bodies of Oppi and Heyerdahl. They climbed down to the two fallen men, but quickly realized that both were dead. Much indicated that one of the safety bolts had come loose during the ascent, and that the guy who had been at the top of the rope had dragged the other with him in the fall. Lundh and Botolfsen spent six hours carrying their dead comrades all the way back to Gjendebu, where Else still was.

The accident made a strong impact on both the local community and the Norwegian climbing community, and it was widely reported in the Norwegian media. Both Heyerdahl and Oppi were experienced climbers, and highly respected in the climbing community. They were both young, newly married men, and both had lost a brother a few years earlier in traffic accidents.

For the Oppi family, this was another hard blow in what began to be a long series of tragedies in just a few years. Not only had they lost one of their best photographers, but also another future heir to the company. There were now very few heirs left. Olga, Eberhard’s widow, was up there in age herself, but ran the company with the good help of Ebba, the only survivor of Eberhard’s four children. Ebba was unmarried and had no children of her own. Karl Thorbjørn Naug was given a more prominent role in the management and care of the company.

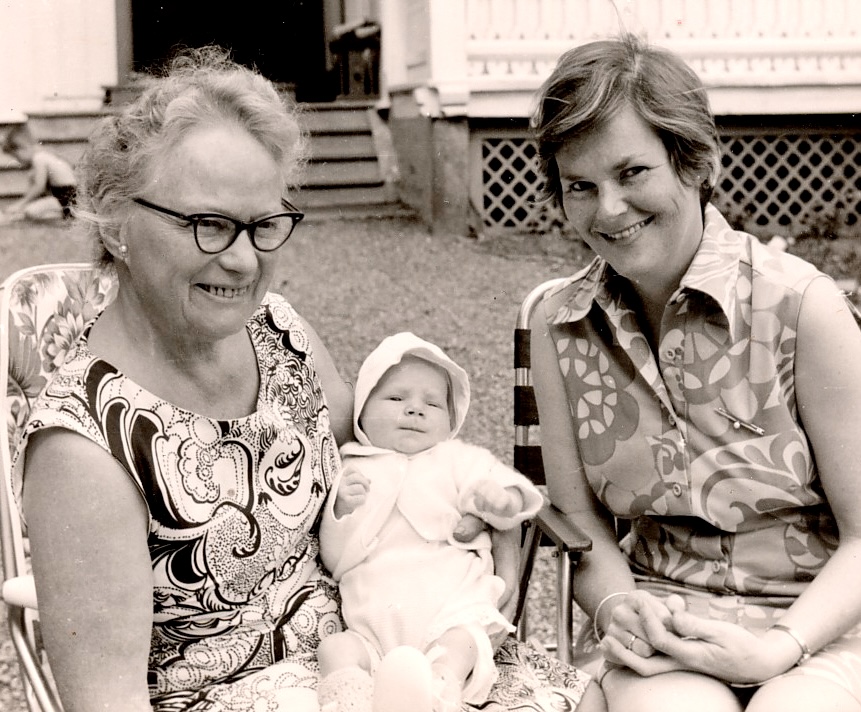

Else Oppi, Per’s wife, who only got two months with her husband after the wedding, later became a flight attendant, and remarried Bjørn Gunnar Braathen, son of Ludvig Braathen, who owned a shipping company and was the founder of the airline Braathens SAFE. The two were visited by Toppen Bech in the TV program “Herskapelig” in 2001.

Fully manufactured in Norway?

If you look online for information about Pan pens and Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk, you can find a number of errors and misconceptions, especially on international websites. I have found a couple of blogs and a few forum threads where people have mixed up the Norwegian Fountain Pen Factory with the Dorn factory that started in Ski in 1950. This also led me astray when I started doing research about these factories a few years ago. The fact is that we had several fountain pen factories in Norway at the time, but Oppi’s factory was the first, largest and most long-lived.

When the Dorn factory in Ski started up in 1950, it was said that they were the country’s only manufacturer of fully manufactured fountain pens. This leads me to believe that Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk perhaps still imported a number of parts from abroad, or possibly that it was known in the industry that they had done so in the 1930s, and that they had not shaken off this perception properly yet at the end of the 1940s. It is also quite likely that pen production at Oppi was at a standstill, or at least greatly reduced during the war, and that it took them a few years to get back up and running properly. Searching for newspaper ads for Pan pens, I have only been able to find a couple of ads from the 40s, and it was only from 1953 onwards that it really started to pick up. Thus it may have been little known in 1950 that Oppi manufactured fountain pens, although they had probably had some regularity in their production since the late 1930s.

There is also a question of how you define “fully manufactured”. None of the Norwegian factories produced their own nibs, for example. They were all imported from abroad. It is also quite certain that the clips and the other metal elements on the Pan pens were bought ready-made from Germany. So what did they actually make at the factory in Oslo? They turned the pen bodies and caps, that’s for sure. But what about the nib sections and the ink feeds, for example? Were they made in Oslo, or were they also imported from Germany? That will be difficult to find an answer to.

The 1950s

The start of the 1950s turned out to be the golden age for Norwegian pen production, driven forward by a shortage of fountain pens due to strict import restrictions. Kristian Hejer started the Dorn pen factory in Ski, Martin O. Nielsen started pen production in Bergen under the brand name Omon, Arnold Wiig started trial production of fountain pens in his factories in Halden, and actually came really close to becoming a Norwegian manufacturer of Parker pens. In 1953, a Norwegian branch of the Danish Miller Pen Co was established in Oslo. Norwegian Reynolds had started its ballpoint pen factory with a bang in 1949, although it went under after just a short time in operation, but at the beginning of the fifties both Norske Ballografverker (a sister factory of the Swedish Ballograf) and Norway Penholder carried out large-scale production of ballpoint pens.

At the start of the 1950s, Pan seemed much more confident in their own brand. The design of the pens appeared more mature and consistent. They also had a new Pan logo. It’s not clear exactly when this logo was launched. I know for sure it must have been between 1947 and 1953. I have a couple of pens of a slightly older design with the new logo, so if I had to guess, I would think it came out in the late 1940s, and definitely not later than 1950.

Zahn, Leser & Co. had shut down in 1943, but started up a new factory again in Heidelberg in 1947. They shut down again around 1954, and some sources suggest they may have moved back to Mannheim then, and kept it going until the end of the 1960s. Whether there was still a collaboration between Eberh. B. Oppi and the German factory during this period, or whether Oppi imported its parts from another supplier, is not known.

What we do know is that they imported nibs from Bock in Heidelberg. The nibs had Oppi’s insignia, and the punchers used to stamp the Oppi logo into the nibs are to this day at the fountain pen museum in Heidelberg. We know for sure that these came from Bock. The celluloid rods used were probably also imported from Germany, and you can see the same materials in use in several German pens from the same period. The same applies to clips and other metal parts.

One factor that may have contributed to them scaling up their own production here in Norway was the strict import rules that applied in the post-war years. There were major restrictions on what could be imported, and high customs duties. At the end of the 1940s, there were a couple of years when the authorities did not allow the import of fountain pens at all, which led to extensive smuggling of pens of poor quality. For several years after the war, there were also very high customs duties on fountain pens, while the rates were lower on parts and materials for pen production and repair.

My theory is that the collaboration with Zahn, Leser & Co. stopped when the German factory was bombed in 1943, and that it was never picked up again after the war. I am unsure whether Zahn, Leser & Co. continued to make Pan pens after the war, or whether from then on it was a purely Norwegian brand. I think it is likely that Oppi may have obtained the full rights to the Pan name when the German factory closed down in 1943. It may also explain why the Norwegian Pan pens got a new logo after the war, while this logo as far as I have managed to find out was not in use in Germany. But this is a theory, and I don’t have sufficient documentation to be able to establish it for sure. What I am sure of, however, is that it was not Zahn, Leser & Co. who made the Pan pens for Oppi from the 1960s and onwards. In other words, Oppi must have been allowed to take the brand name on to other manufacturers.

The pens

How good were the Pan pens really? How did they stack up against other pens on the market at the time? Pan was no Parker or Montblanc, they weren’t premium pens, but they were also a good deal cheaper than the more well-known pens. However, the nibs were very good, and well on par with anything else on the market. While the larger and better-known brands after the war began to experiment with new and more complex filling systems, materials and manufacturing methods, throughout almost the entire 1950s Pan stuck to button fillers, turned by celluloid rods and fairly traditional pen designs.

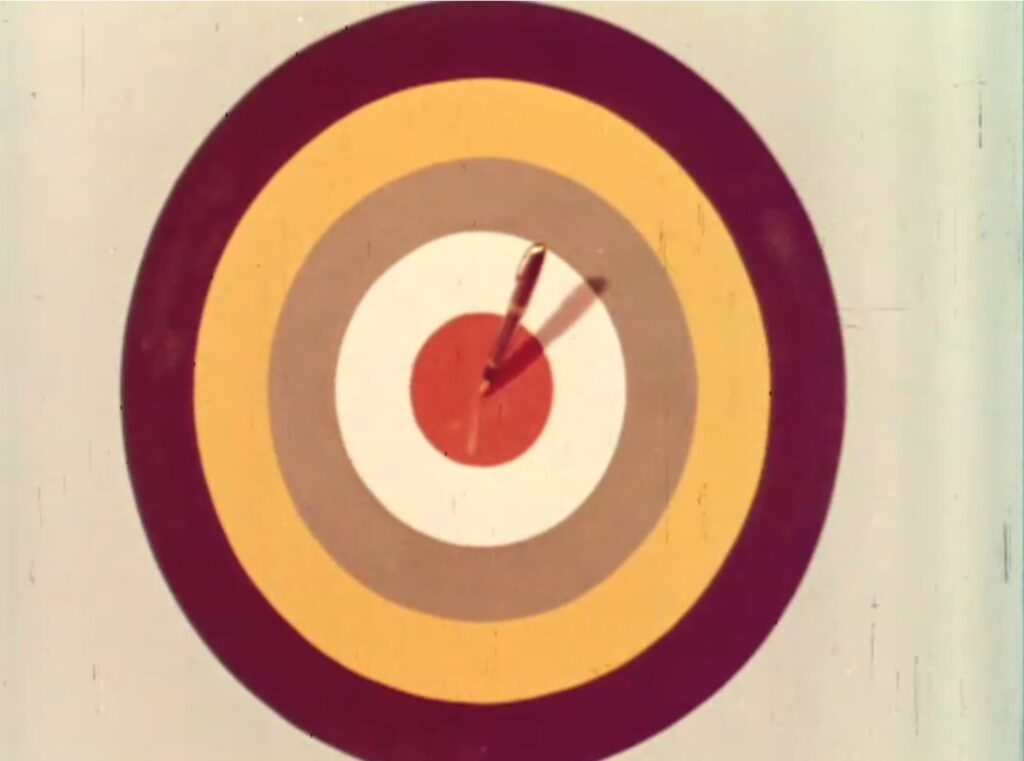

Pictures from a video advertisement for Pan pens from 1958. The video is available at the online library of the Norwegian National Library.

There was nothing groundbreaking or innovative about the pens from Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk. They stuck to methods and materials that had been in use for 20-30 years at this point, but they made excellent pens. It was also clear that Oppi had faith in the quality of their own pens, because they were sold with a guarantee without a time limit. If Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk had still been in operation, to this day you could have gone to them with a 1950s Pan pen and complained about manufacturing defects.

The Pan pens came in several editions, sizes and price ranges. The cheapest ones were called Pan Junior. They were popular confirmation gifts, and often came with steel nibs, although in some places you could also get gold nibs for them. In the mid-1950s, a Pan Junior cost NOK 21,-. All the other Pan models in the 1950s were supplied with gold nibs as standard.

At the other end of the scale, there was the Pan Senior, which was the most expensive of the pens in the standard size, at NOK 55,-. This was in roughly the same price range as the Parker Duofold and Pelikan 100N, good pens that had been on the market for a number of years, but were no longer top models of their respective brands.

Between Junior and Senior, Pan had a long range of pens with model numbers based on price (Pan 27, Pan 35, Pan 45 etc. They cost NOK 27,-, 35,- or 45,- respectively). Like the Pan Junior, the Pan 27 was also very popular as a confirmation or graduation gift.

The Pan 40 Lady Pen cost NOK 40,-, as the model number suggests. It was slightly smaller in size than the other pens.

Additionally, they had a couple of pens that appear to have been given model numbers based on the year they were released. In my own collection I have a couple of Pan 52, and some Pan 53s. In the price lists I have found, they were listed at NOK 40,-.

At the very top of the Pan hierarchy sat the Pan Diplomat, at NOK 75,-. This was an oversize pen, and a good deal larger than the standard pens, which was also reflected in the price. In comparison, in Norway, Pelikan 400 was sold for NOK 71,-. It’s a well-known and accomplished pen, but not an oversize. The Parker 51 and Sheaffer Snorkel were two very trendy and modern pens at the time, but cost over twice as much as a Pan Diplomat. Both of these had a list price in this country of around NOK 160,-.

Import

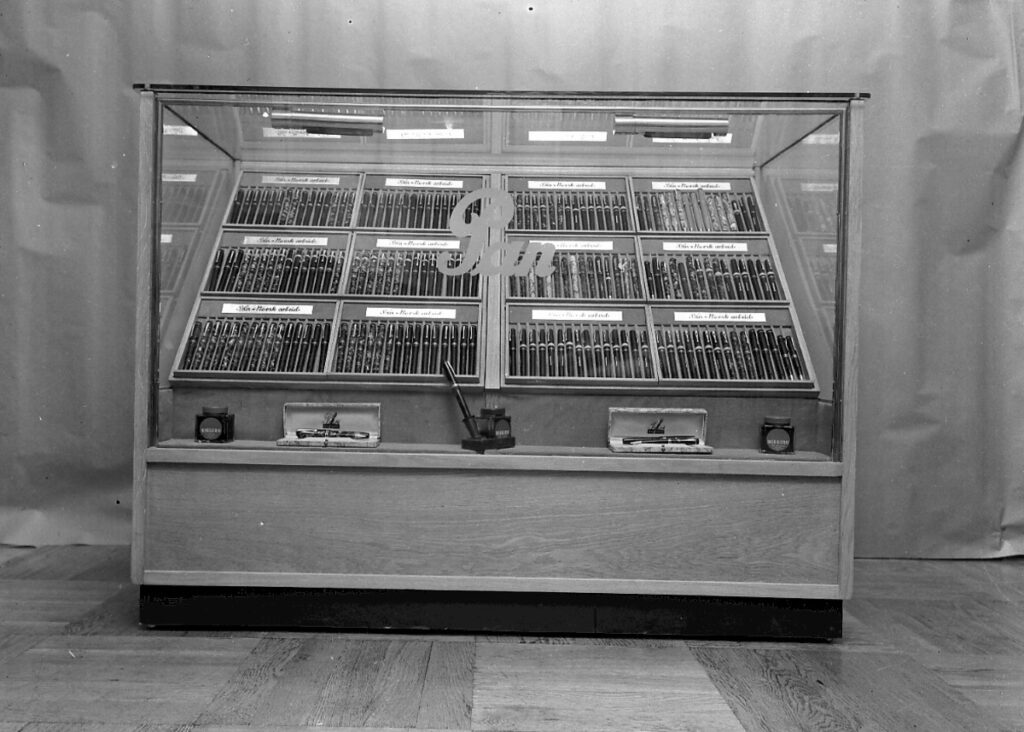

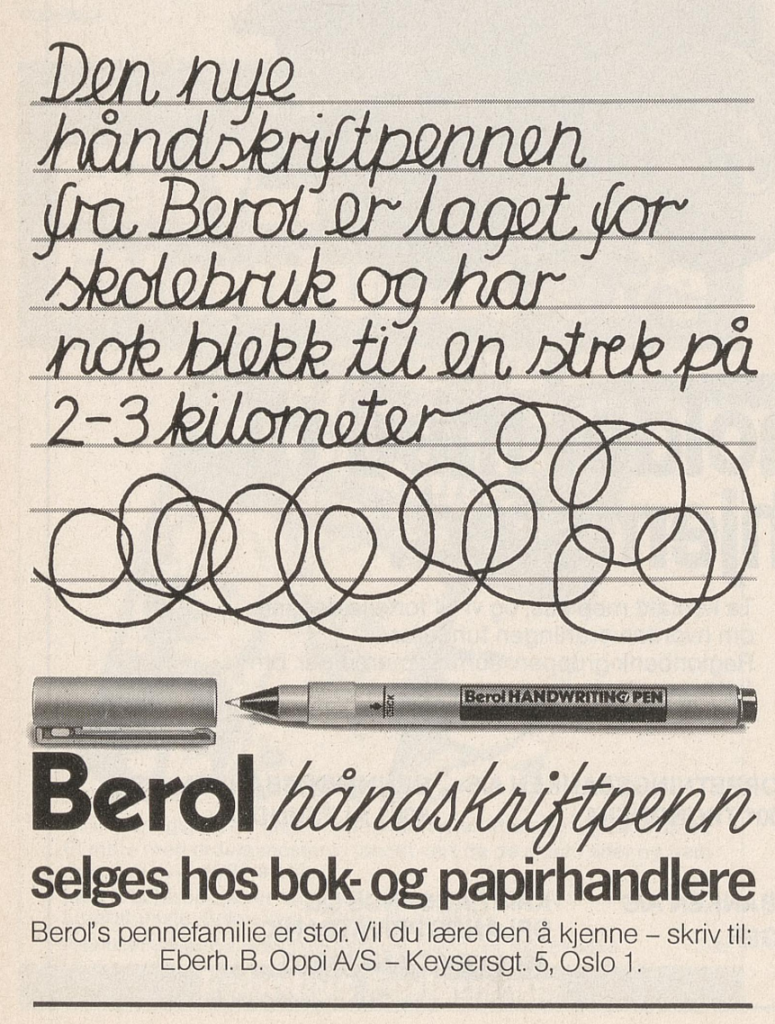

Eberh. B. Oppi also imported a number of stationery, pencils, paper products, etc. both before and after the war. Among other things, they had a deal with the Eagle Pencil Company , later Berol , for several decades. I have found a number of photos taken in Oppi’s premises in Keysers gate 5 in the 1930s, and on some of them you can see trays of Eagle Prestige fountain pens.

The Eagle Pencil Company was founded in 1856 in New York by Daniel Berolzheimer, whose family also owned a pencil factory in Germany. Eagle eventually also had factories in Canada and England. In 1969 they changed their name to Berol.

Oppi was the sole importer of Sheaffer pens for a period. At least that’s what they claimed in an ad in 1967. In another Sheaffer ad from 1957, however, it’s Mittet & Co . who is listed as sole importer. Incidentally, Mittet was also a large art publisher, sold a lot of postcards, imported writing equipment, and was probably Oppi’s biggest competitor in almost all areas.

Oppi was also an agent for Montblanc. Among other things, they were the ones who serviced King Olav V’s Montblanc pen when it needed some care. Then a royal ordinance came from the castle down to Keyser’s gate 5 with the king’s pen.

Greta Gundersen

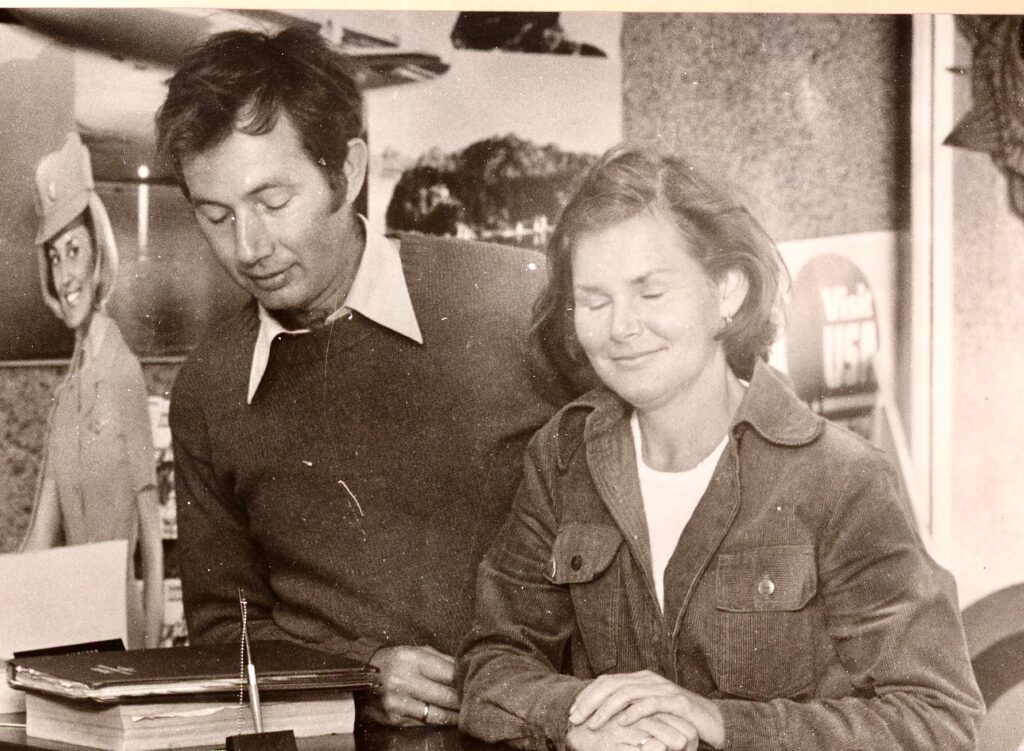

Olga Oppi died in 1955, and in 1961 a new board member joined Eberh. B. Oppi: a young woman named Greta Gundersen. In 1964, she married Ole-Jørgen Christiansen, and then changed her name to Christiansen. In 1973, she took over as chairman of the board of the company, and sat in this role throughout the rest of the company’s lifetime.

For a long time it was a mystery to me who Greta actually was. There was no one else (that I had found) with either the Gundersen or Christiansen name in the Oppi or Naug family. For a while I thought she could be Eberhard’s eldest daughter, but I eventually found out that the eldest daughter’s name was Hjørdis, and died in 1905. Then I thought that Greta might be the daughter of Ebba Oppi, Eberhard’s second daughter from his marriage to Inga, but couldn’t quite piece that together either. Ebba is consistently referred to as “Ms. Ebba Oppi”, which suggests that she was unmarried. She was also slightly too old to be Greta’s mother.

After quite a lot of searching, I found a newspaper interview with Greta from 1999, where she is referred to as Greta Oppi Christiansen. So she was definitely an Oppi! But how did she fit into the family? It started to unravel when I found the website of Per-Otto Oppi Christiansen, who states that “My grandfather and his brother were photographers for Kunstforlaget Eberh. B. Oppi As, founded by my great-grandfather”. With the surname “Oppi Christiansen”, it was quite obvious that Per-Otto had to be the son of Greta and Ole-Jørgen. And from what he wrote, Greta had to be the daughter of either Bjørn or Per Oppi.

I also eventually found the obituary of Gerd Brath, who was married to Bjørn Oppi. In the obituary she was listed as Gerd Brath Gundersen, and then the pieces finally started to fall into place. Gerd and Bjørn had Greta in the winter of 1939. The following year Bjørn died in Åndalsnes, and a few years later Gerd remarried, to Ivar Gundersen, who adopted Greta. Thus she became a Gundersen. She kept Oppi as her middle name, but this name was not used in the trade register, where she is listed as a board member, and eventually chairman of Eberh. B. Oppi.

This reasoning was later confirmed when I came into contact with her sons, Hans-Jørgen and Per-Otto. Of Eberhard Oppi’s four descendants, only one had a child of his own, before he was tragically killed during the war. Hjørdis lived to be only five years old, and Per died before he could have children of his own. Ebba never married and had no children. Greta was thus the only descendant who could inherit the company, if it were to remain in the family. Fortunately, they also had the Naug family to lean on, where the seat on the board eventually passed from father Karl Thorbjørn to son Knut.

Knut Naug

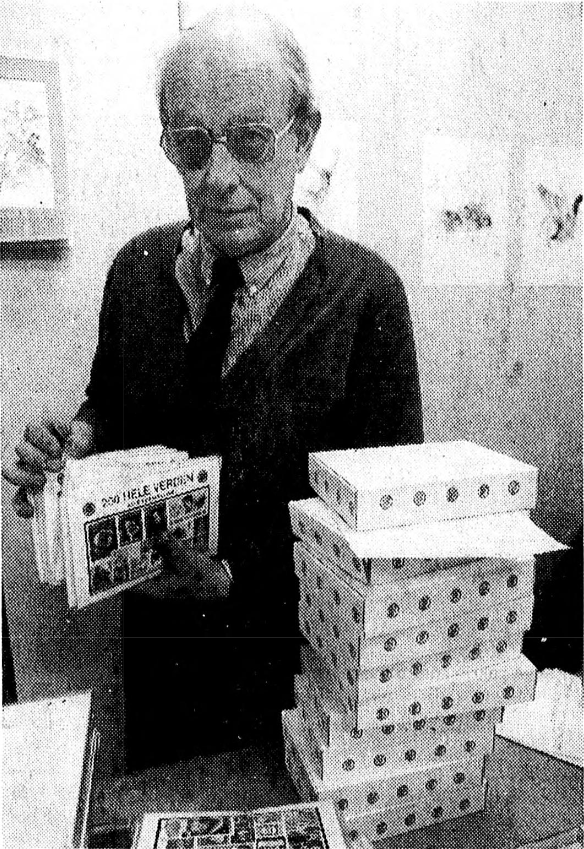

It is unclear when Knut Naug started working at Eberh. B. Oppi, but we can assume that he worked there from a fairly young age, especially as the publishing house had become a family business for the Naug family as well, after Karl Thorbjørn Naug became a shareholder and board member. Naug senior also sat for a period as chairman of the board, in addition to being office manager. Knut stated in an interview in the newspaper Aftenposten in 1982 that he remembered how in the past they had made fountain pens at the lathes, and if we are to take this statement literally, we can assume that he at least worked for the company in the 50s.

What is certain is that Knut Naug was given the company’s power of attorney in 1963. He was not on the board yet, but must have had a prominent role in the day-to-day operations. It is probably conceivable that he had become office manager at this time. The father was in his mid-60s in 1963, so it would have been natural for him to leave some of the tasks to the next generation.

Knut Naug took over his father’s shares and board seat in the company in 1973, and Karl Thorbjørn Naug passed away on July 20, 1977, aged 80.

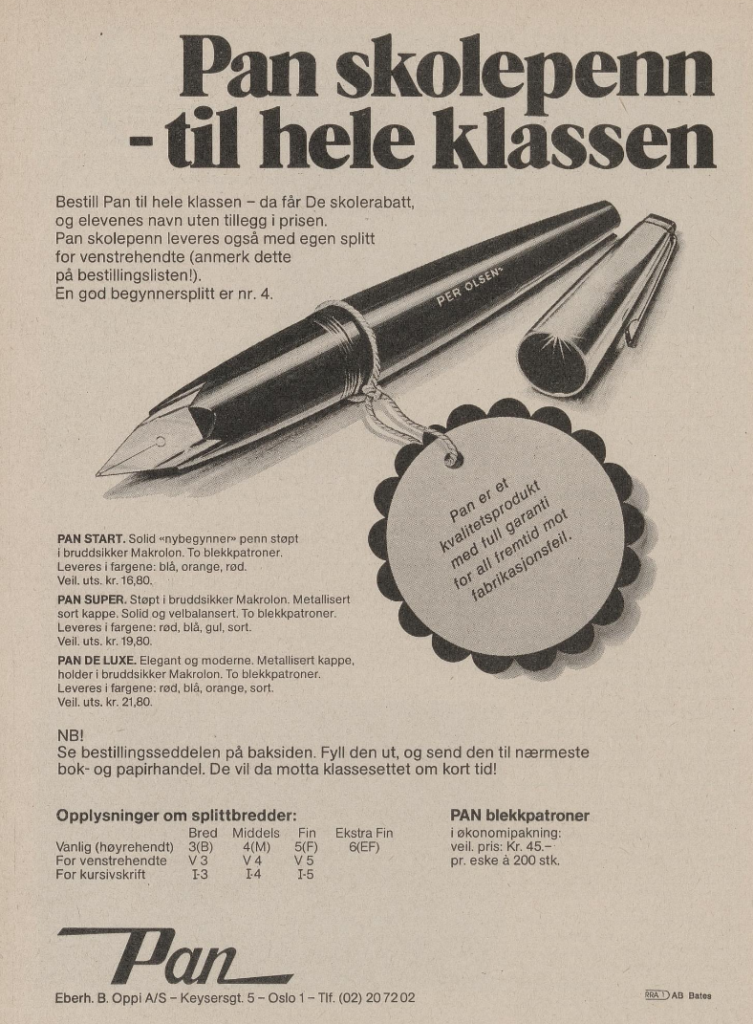

School pens

From around 1960, Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk gradually switched from making fountain pens first and foremost for the adult population, to primarily making school pens. Fountain pens had largely been replaced by ballpoint pens in society by this time, but in Norwegian schools it was only now that they were being used on a large scale. Up until the beginning of the 60s, most Norwegian schools had used dip pens and inkwells, with the inevitable smudges and spills, but from the beginning of the 1960s more and more schools started using fountain pens instead, and by 1970 this had become more or less standard in all Norwegian schools.

With the entry of fountain pens into schools, it soon became necessary for the pen brands to rethink their strategies. Prices had to come down, so that it was affordable for parents to buy pens for their children, and the pens themselves had to be adapted to small children’s hands. Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk stopped making the pens themselves in their own premises. The pens were no longer hand-turned, but made out of injection-molded plastic at a factory in Germany. The parts were then imported to Norway, and assembled and distributed by Eberh. B. Oppi.

With this method, one could make a much larger number of pens in a shorter time, and at the same time sell them at a much lower price. The quality of the pens themselves necessarily also declined, but the writing properties were still impeccable.

As early as 1958, Pan started making school pens, with its Pan Populær at NOK 19,-. They also had another, slightly cheaper, school pen that was simply called “Pan”, for NOK 12,-. The following year they launched two new school pens, namely Formpoint (NOK 12,-) and Superpoint (NOK 16,-). Both of these had piston filling, and were probably not made in Norway. The pens were now mostly in one colour, and with a simpler and more modern design throughout.

Then, in 1960, Pelikan launched the first version of its Pelikano school pen. It immediately became a huge success, and set a new standard for what a school pen should be. Until the 1960s, school pens had only been modified ‘adult’ pens, but the Pelikano marked a new approach to school pens. Pelikan relied on an extensive survey of thousands of teachers when designing it. The Pelikano was lighter in weight, had a robust nib that would withstand inexperienced writing hands, and it was filled using cartridges, which was was easier and more practical than ink bottles. Not least, it was designed to be sold relatively cheaply, so that it would be affordable to get fountain pens for the children, whether it was the parents or the schools who had to pay for it.

Everyone else in the industry immediately had to adapt in order not to lose ground in the competition against this new innovation. That said, Pelikan was unable to meet demands at first. They made over a million pelikanos in the first four years after its launch, but it wasn’t nearly enough. This opened up opportunities for other fountain pen brands that could come out with similar pens.

In 1962, the first Pan pen with cartridge filling came out. It was simply called Pan 15 Patron (Cartridge), and cost NOK 15,-. And it was very similar to the Pelikano. In the years that followed, there was a long line of school pens from Pan that were all based on the same basic design, with slight differences from year to year and between the various price ranges. They largely continued the tradition they had started in the 1950s, where the pens were named after what they cost.

Mutschler

In an interview with manager Knut Naug in Aftenposten on March 3, 1982, it was stated:

Fountain pen production requires only a couple of the company’s twenty employees. Dispatcher Knut Naug remembers when it was a labor-intensive operation to make a fountain pen. With lathes, celluloid tubes were used and shaped into a durable writing instrument. Now the job mostly consists of checking and assembling ready-made parts from Germany.

I have long wondered which German factory made the parts for Pan’s school pens. I had a strong suspicion that it was not the same factory that had made the Pan pens of the 1930s. I had almost given up on finding out, when almost by chance I had a breakthrough after some communication with Thomas Neureither at the fountain pen museum in Heidelberg.

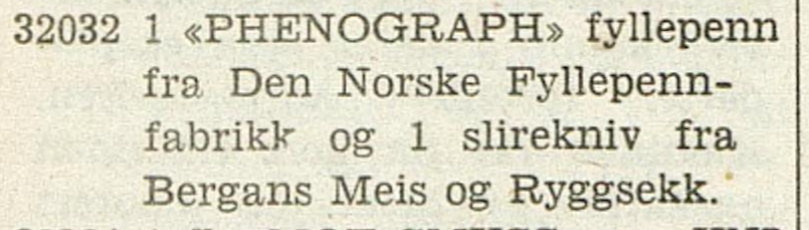

I asked him if he had come across a pen model called “Phenograph” in Germany. This was based on a newspaper clipping I had found where a “Phenograph from Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk” was listed as one of the prizes in a lottery in 1964, but I had not found any ads, pictures or other info about this particular pen, and the name piqued my curiosity. Pan didn’t have any other pens with a similar name. Neureither then mentioned that the name of the pen reminded him of certain technical pens that Mutschler had made, and that Mutschler was a large factory in Heidelberg that made inexpensive pens on behalf of many other brands.

After a round of Google searches, I found very little about Mutschler, but they were mentioned in an article I found about a brand called Laurin. Laurin was acquired by Pelikan in 1972, but continued to sell cheap pens under its own name for many years. These pens were made by Mutschler, and if you find pictures of a Laurin Model 854 from 1975 and compare with a Pan school pen from the same year, the differences are miniscule. They both have exactly the same grip, nib and feed. There were too many similarities for it to be a coincidence, and I could then conclude that the Pan school pens from the 1960s and 70s must have been made by Mutschler.

Philip Mutschler originally worked at the Kaweco factory in Heidelberg, but the factory experienced downturns in the 1920s. Mutschler brought some of his colleagues with him, and started his own factory instead. Mutschler was one of the very first to use injection molded plastic parts in their pens. This made it possible to produce a large number of pens much faster than before, and much more affordably. They had a collaboration with the Reform factory in Nieder-Ramstadt, and when this went bankrupt in 1956, the brand name Reform lived on in the pens of Mutschler. Several Pan pens actually have nibs with the Reform logo on them, which is a good indication that it was precisely this factory that made the pens for Oppi from the 1960s and onwards.

Mutschler bought the nib factory Degussa in the 1980s, and then shifted focus from pen production to primarily making nibs. They closed their factory doors for the last time in 2003.

Various advertisements, 1964-1978

From the mid-1950s and onwards, fountain pens were largely dying out among the adult population. The more practical ballpoint pens had taken over most of the market share for this user group. But as soon as the primary schools started using fountain pens on a large scale, a completely new and much larger market opened up, and this is clearly shown in the marketing from Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk. From the 1960s and 70s, you can find a flurry of different newspaper ads and advertisements for the Pan school pens. Here are various advertisements from each year in the period 1964-1978:

The 1980s and 90s

Ebba Oppi died in 1986, and after this it was primarily Greta and her husband, Ole-Jørgen, who managed the company. It is unknown whether Knut Naug still worked there then. He was over 70 years old at this time.

Eberh. B. Oppi was sold to Emo AS in 1988. Emo was a large company, and Oppi had many different agencies and agreements with well-known brands that Emo was interested in. The last year Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk was listed in the Oslo address book was in 1989. it is possible that Emo continued parts of Oppi for a period after the acquisition, but the traces of the family company stop at the end of the 1980s. At this time, Oppi had 25-30 employees, and all of these were offered to continue in Emo after the purchase.

Ole-Jørgen Christiansen, who had worked at the art publisher since he married Greta in 1964, and who was also involved on the board of directors, joined Emo, and sat for a few years as an advisor and consultant until he retired. Officially, the company Eberh. B. Oppi was disbanded in 1995.

Emo is today owned by Lyreco (formerly Staples Norway), and is one of Norway’s largest players in the sale and distribution of office supplies.

The Oppi family had a lot of material from the art publishing house for a long time. Eventually they donated a large amount of photographs and negatives to the Preuss Photo Museum in Horten. Ole-Jørgen passed away in 2020, but Greta is still alive, and is now 84 years old. She and her family has had the opportunity to read this article before it was published.

Conclusion

As I have written about in several articles here on the blog, there were several companies who tried to start up fountain pen production in Norway, especially at the beginning of the 1950s, but most of them disappeared after a few years. Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk, on the other hand, held its own for several decades. They had, as I see it, three major advantages:

Firstly, they quickly realized that they had to capture as large a share of the market for school pens as possible. They started selling school pens before it was common to write with fountain pens in Norwegian schools, and were thus already a well-known name in the school system when schools eventually made the leap from dip pens to fountain pens.

They were also part of a larger company that was very successful in other arenas, both as a publisher, and also as an importer of other pens and stationery. This made Eberh. B. Oppi more robust against fluctuations in the market than those who invested exclusively in pen production, and thus they probably withstood to a greater extent the transition that began to take place in the second half of the 1950s.

The third advantage they had was experience. Eberh. B. Oppi had been involved in both the import and production of pens since the early 1930s. They then had an advantage over those who started with this in 1950. They perhaps had a greater sense of the direction in which the market was moving, and they had more contacts and collaboration partners abroad that they could make use of.

Today Eberh. B. Oppi is still well known for their postcards, and when you google the name, you can find a lot of motifs from postcards and Christmas cards.

The Pan pens have their own status. When I talk to people a little older than myself about my hobby, and mention that I collect Pan pens, a lot of Norwegians remember having a Pan school pen in their youth. Here in Norway, I have the impression that Pan was probably as popular as Pelikano at school, if not even more so. The Pan school pens are also fairly easy to come by in antique shops, garage sales, etc.

The family logo, the characteristic circular O with two P’s and an I inside, is still in use. Per-Otto Oppi Christiansen, who is Eberhard’s great-grandson, uses it today as a logo for his business as a photographer. He is carrying on a small part of the brand that the family built up back in the days. Through his work as a photographer, he has also taken up the legacy of his grandfather, Bjørn.

Eberhard Bredesen Oppi’s old neighbor in Bogstadveien 25 was right when he said that “there was buoyancy in him”. His art publishing house grew to become one of the largest and most recognized in the country, and the pen factory, which was only a small part of the company, was to become the most long-lived and most accomplished in Norwegian history. Today, 35 years after Eberh. B. Oppi was shut down, they are still remembered for both their publishing activities and their pens. That is not a bad legacy for the 14-year-old who in his time moved to the capital to become a barber’s apprentice.

Many thanks to Hans-Jørgen and Per-Otto Oppi Christiansen for useful help and clarifications in the work on this article. They also sent me pictures I could use of Bjørn Oppi, Ebba, Greta and Ole-Jørgen.

Thanks also to Thomas Neureither at the Füllhaltermuseum Handschuhsheim for invaluable information on the German pen factories, as well as a couple of the photos used in this article.

Sources:

Most sources are in Norwegian.

Wikipedia – Åndalsnes

Wikipedia – Bombing of Mannheim in World War II

pelikan-collectibles.com – Laurin – Pelikan Plant Waiblingen

pelikan-collectibles.com – Pelikan Pelikano

Lokalhistoriewiki.no – Eberhard Bredesen Oppi

Histreg.no – Eberhard Bredesen Oppi

Christiania Nyheds- og Advertissementsblad, 04.08.1897 – “Barber”

Aftenposten, 10.08.1899 – “En Datter født idag”

Norsk Kundgjørelsestidende, 15.04.1902 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Norsk Kundgjørelsestidende, 24.04.1902 – “Oppi & Co.”

Aftenposten, 17.02.1905 – “Vor elskede Datter…”

Aftenposten, 16.03.1905 – “Min kjære Hustru…”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1905 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Aftenposten, 21.11 1907 – “Ingen i Norge”

Aftenposten, 06.03.1909 – “En Konkursbeholdning”

Norges Handel – Sjøfart og Industri – i Tekst og Billeder, 1914 – “Eberh. B. Oppi, Kunstforlag”

Fra Norges Næringsliv, dets Mænd og Institutioner ved begyndelsen av 20. aarhundrede 4: Den Grafiske Branche, 1915 – “Eberh. B. Oppi. Kunstforlag – Kristiania”

Norges Handelskalender, 1915 – “Oppi, Eberh. B, Kunstforlag”

Tidens Tegn, 07.03.1917 – “Meddelelse!”

Dagbladet, 22.12.1920 – “Juleglæde”/”Norges Natur”

Social-Demokraten, 22.12.1921 – “Norges Musikhistorie”

Norges Handel-Sjøfart og Industri – i tekst og billeder, Kristiania i 1924, 1924 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Trondhjems Adresseavis, 14.12.1925 – “Blinde barns fyrstikker”

Hedemarkens Amtstidende, 09.02.1928 – “En 50-åring”

Nationen, 18.01.1930 – “Lettlands konsul i Oslo”

Oslo Adressebok, 1934 – “Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk”

Østfold Regiments Befalslag 1884-1934, 1934 – “Karl Thorbjørn Naug”

Arbeiderbladet, 08.02.1938 – “60 år”

Nationen, 08.02.1938 – “60 år”

Fredriksstad Blad, 23.03.1938 – “Bryllup”

Norsk Musikkgranskning, 1938 – “Året 1938”

Norsk Lysingsblad, 23.01.1940 – “Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk”

Arbeiderbladet, 04.05.1940 – “Dødsfall”

Aftenposten, 06.05.1940 – Dødsannonse, Eberhard B. Oppi

Vestfold, 22.05.1940 – “Bjørn Oppi er død ved Åndalsnes”

Dalane Tidende, 24.05.1940 – “Et nytt slag har rammet…”

Halden Arbeiderblad, 07.06.1940 – “En hardt ramt familie”

Norsk Lysingsblad, 12.06.1940 – “Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk”

Aftenposten, 12.03.1941 – “Vellykket årskonkurranse i Oslo Kameraklubb”

Asker og Bærums Budstikke, 30.06.1941 – “Til handelsregistret er anmeldt”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1941 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Bildet lever – Oslo Kameraklubbs fotokavalkade 1921-1946, 1946 – “Fargefotogruppen”

Aftenposten 23.12.1947 – “Forlovede”

Vårt Land, 20.05.1948 – “Bryllup”

Romsdal Folkeblad, 29.07.1948 – “Trist ulykke i fjellet”

Dagningen, 30.07.1948 – “Fryktelig ulykke i Jotunheimen”

Velgeren, 31.07.1948 – “Tragiske omstendigheter knyttet til ulykken ved Tyin”

Østlands-posten, 05.08.1948 – “Ulykken rammet to nygifte menn”

Våre Falne 1939-1945, 1950 – “Oppi, Bjørn”

Nordlands Framtid, 08.05.1953 – “Konfirmanten”

Hamar Arbeiderblad, 15.12.1955 – “En god fyllepenn er en meget kjærkommen julegave”

Haugesunds Dagblad, 23.08.1956 – “Skoleungdom”

Namdal Arbeiderblad, 11.12.1956 – “Fyllepenner”

Ringerikes Blad, 22.08.1958 – “Skolefyllepenner”

Norsk Fjellsport, 1958 – “Anton Heyerdahl”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1961 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Ringeriks-slekten Færden, 1963 – Else Færden

Fredriksstad Blad, 24.05.1963 – “Forlovelse”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1963 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Fredriksstad Blad, 15.01.1964 – “Bryllup”

Morgenposten, 10.12.1964 – “Phenograph”

Ringerikes Blad, 15.08.1966 – “Skolefyllepenner!”

Adresseavisen, 06.12.1967 – “Sheaffer”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1969 – “A/S Keysersgt. 5”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1972 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1973 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Handelsregistre for Kongeriket Norge, 1975 – “Eberh. B. Oppi”

Asker og Bærums Budstikke, 28.07.1977 – Dødsannonse, Karl Thorbjørn Naug

Fredriksstad Blad, 27.06.1981 – Dødsannonse Gerd Brath Gundersen

Aftenposten, 03.03.1982 – “Oslo-firma står mot tusjpennene”

Hof Bygdebok B. 2 – Gards- og slektshistorie for Sør-Jara og Mosogn, 1985 – “Bnr. 8 (lnr. 766 b, 767 c) OPPI”

Oslo Adressebok, 1989-90 – “Den Norske Fyllepennfabrikk”

Aftenposten, 17.08.1995 – “Kreditorvarsel – Oppløsning”

Aftenposten, 29.12.1997 – “Med hjerte for Oslo”

Fredriksstad Blad, 25.07.1999 – “Freidige frøkner”

Fronsbygdin, årbok 2012, 2012 – “Du e’ hiven, du Glott!”

VG Spesial – Våre falne, 2015 – “Bjørn Oppi”

Fjuken, 06.09.2018 – “For 70 år sidan fall to klatrarar ned frå Knutsholstind og omkom”

Aalesund – Byen som brente, 2018 – “Oppi Kunstforlag, Eberh. B. (Kristiania)”

Norske postkort – tegnere, signaturer, utgivere, 2018 – “Oppi”

One thought on “Nibby Sunday – “There was buoyancy in him” – The Story of Eberhard Bredesen Oppi and The Norwegian Fountain Pen Factory”