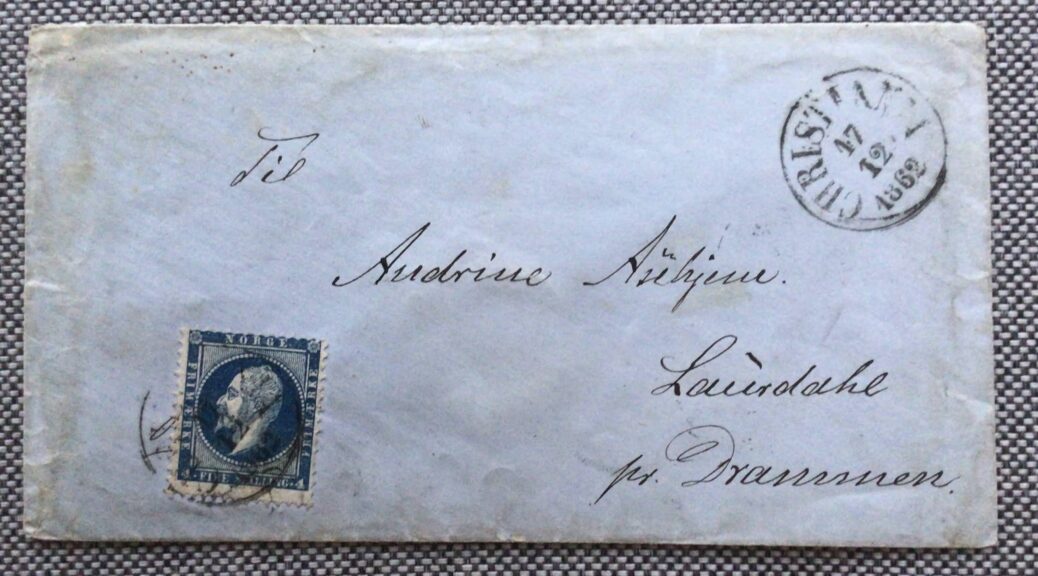

Point to Paper – She got a very special envelope from her husband on the 17th of December 1862

On the 17th of December 1862, Andrine Aschjem received a letter from her husband Hans Jakob. The letter was addressed Laurdahl. To find her home in Norway on a map today you would have to look for the farm Grini in Lardal in the county of Vestfold. The farm still exists.

It was just before Christmas. I think Andrine was busy in the house baking and cooking. It was probably cold outside. She might have been having trouble with the snow that day. I think she could have been baking “Fattigmann” and “Lefse”. Maybe the “Ribbe” and the “Fårerull” was cooking and the “Lutefisk” was being prepared. The Aschjems had a dependeble income. They could afford all the finest Norwegian Christmas traditions.

Unfortunately, the letter she got that day has been lost. I would have loved to have known what was written there. Maybe Hans Jakob just wanted to know if everything was ready for the holidays. Maybe he wanted to know if he should bring something home from the capital. He might have been asking Andrine if there was anything special she wanted for Christmas. I am considering making up an imaginary letter in another post to replace the one that has been lost forever. That is not the topic today though. The letter is lost but that is in no way the end of the story. There is plenty left to write about. Today’s post is about the very special envelope the letter came in.

Stamp collectors and letter collectors often overlook the envelope. Today I want to show that this envelope is worth a closer look. It has its own story to tell. It is much more interesting than I thought it would be when I got hold of it. Actually, at first I really didn’t think about the envolope at all. What made me reflect on it was a post on this very blog. Anders Kristiansen wrote about the forgotten letters that were found by postmaster Simon de Briennes in 1707. Anders mentioned, among other things, something about the world’s first envelope folding machine. It made me wonder if it was normal to send a letter in an envelope in Norway in 1862. I was going to discover that this was actually a rare thing at the time.

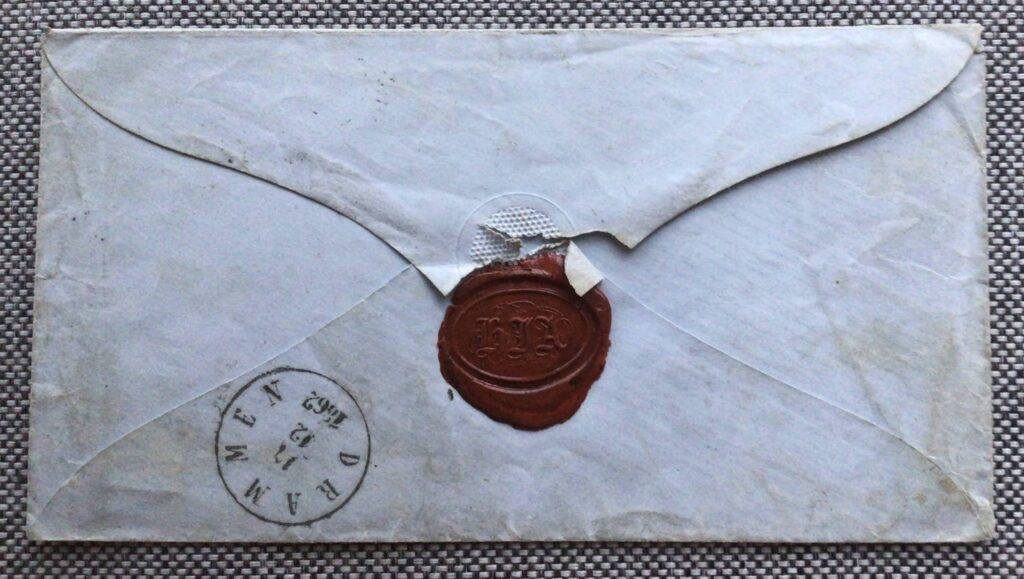

Andrine’s envelope is probably one of the very first to be used in Norway. In 1862, the machine-made envelope was a technological innovation. Along with the creation of the postal service and the ingenious idea of using stamps to pay for sending letters, the humble envelope was an invention that has gained enormous importance for long-distance communication between people. The envelope was the container that took care of the precious words. At this time in history, the words were usually written in ink. The envelope prevented access and safeguarded privacy. On the outside there was only a name, an address, a stamp and some transport information.

The envelope and its content has a high legal status. It is still protected by strickt laws. Many countries have severe penalties for losing, stealing or opening other people’s mail. In the US the following law applies – 18 US Code § 1708 – Theft or receipt of stolen mail matter generally. The law states that stealing or opening other people’s mail can lead to up to five years in prison. There are postal employees who have received long sentences for stealing mail. An example is the postman Gabriel March Granados . He worked at a post office on the island of Mallorca in the Mediterranian. He started the job on the 28th of January 1968, just 18 years old. Two years later, on the 31st of March 1970, he was fired. The post office in the island’s capital, Palma de Mallorca, reported the matter to the police. After an extensive investigation, he was accused of stealing 42 768 letters. The prosecutor proposed 384 912 years in prison. This corresponds to 9 years for each stolen letter. He was eventually sentenced to 14 years behind bars.

It wasn’t just anyone who could afford envelopes in 1862. Andrine’s husband was a member of the Norwegian Parliament. His name was Hans Jakob Aschjem. It was Hans Jakob’s first year as a representative. He may well have gained access to this modern form of office supplies through his job in the government.

In an upcoming post, I will write about another letter that was sent to Andrine. It was a letter that she received from her friend Lise Kahrs. Despite the fact that Lise Kahrs was a fine young lady from Kristiania, she did not use an envelope for the letter she wrote to her friend Andrine in 1858. In the letter, Lise is clear about how much she values her friend. The letter is politely addressed to Madame Andrine Aschjem. Presumably, the lack of an envelope shows that they were not in common use in Norway as late as 1858. I think Lise would have used an envelope if she had had access to one.

I have for years looked for older Norwegian envelopes at auctions and online sites and have actually only found one with an earlier date. It is a business envelope that was sent to Franz Heinrich Feddersen in Hammerfest from Den Norske Creditbank Christiania. The letter was sent “Recommanderet” (signed for) on the 11th of April 1858. The envelope from Den Norske Creditbank Christiania is probably also one of the very first used in Norway with a pre-printed logo. If any of the readers know of an older Norwegian envelope, we are grateful for input. Our blog seems to be doing pioneer research in this field. As you will see later, even Store Norske Leksikon (The Great Norwegian Encyclopedia) stated that the envelope was invented in 1878 until we presented our findings to them.

Internationally, Edwin Hill and Warren de la Rue took out the first patent for an envelope folding machine in 1845. It is no coincidence that Edwin Hill had become aware of the problem. It was his brother, (Sir) Rowland Hill, who published The Post Office Reform in 1837. Before the reform, postage was paid by the recipient and the price was calculated based on a combination of how many sheets the letter consisted of and how far it had travelled. Sending mail was complicated and expensive. It also sometimes contributed to that some recipients simply could not afford to accept the letters they were sent.

Creative poor families, who could read and write, even found ways to send messages to each other without having to pay to receive the letter. Rowland Hill once joined a postman that was to deliver a letter to a poor maid. She could not afford to pay the postage fee. She got to see the envelope, but chose to return it. Hill took pity on the girl and paid the postage for her. The postman then gave the girl the letter. The reaction was not quite as expected. Hill asked if she could explain. She reluctantly told him that she did not need to open the letter because the message from the family had already been given through secret marks on the outside of the envelope.

Rowland Hill, who had no postal service experience, was hired to analyze the organization. He quickly saw that something had to be done. He calculated what it actually cost on average to send a letter and he proposed a fixed, reasonable domestic postage rate. The idea was radical. It was going to revolutionize the postal service and accelerate the amount of mail sent both in Britain and the rest of the world. Sending a letter would cost only a fraction of what it had cost in the past.

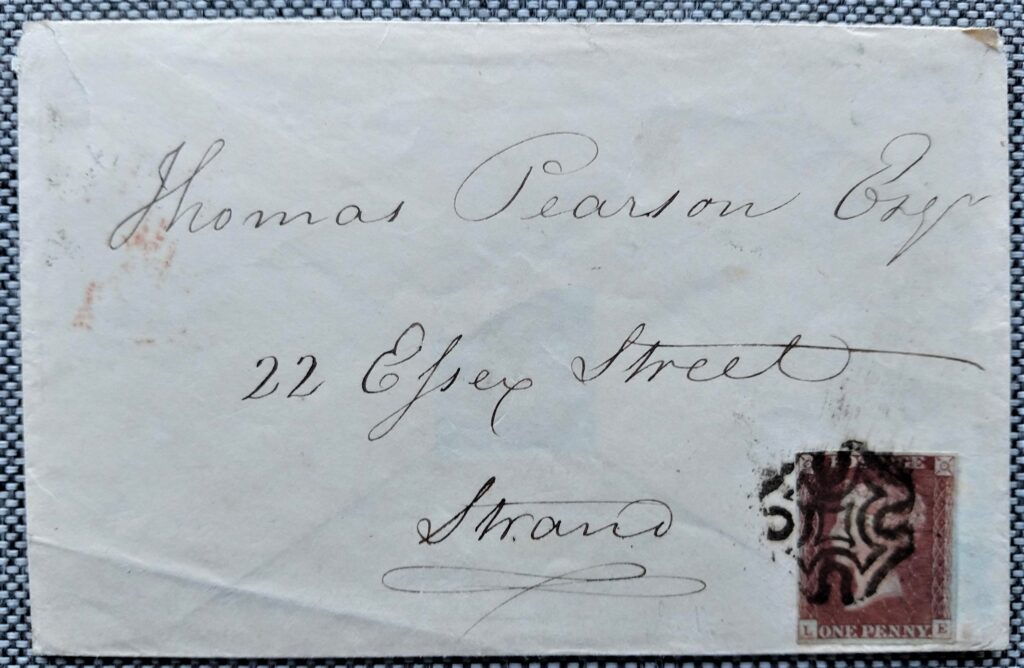

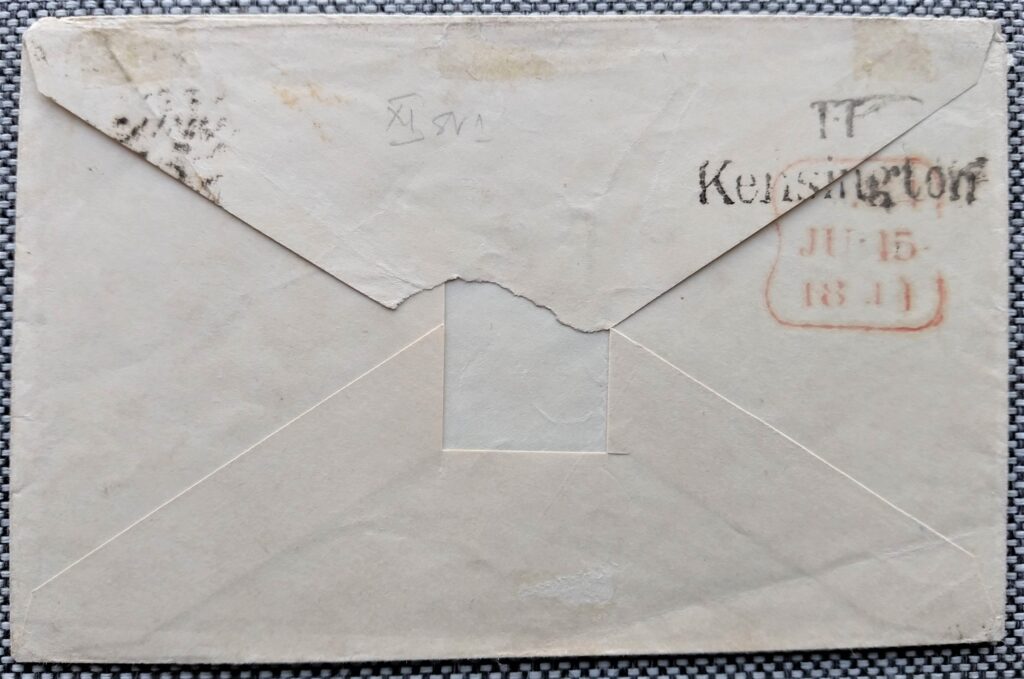

The envelope was actually in the beginning a direct competitor to the stamp. From the 6th of May 1840, customers in Great Britain could choose whether they wanted to send letters in a prepaid envelope, a Mulready envelope, or use a stamp that they could put on their letter either it was just foldet or put in another type of envelope. Both versions cost 1 penny. On the 5th of December 1839 the price for domestic postage was set at only 4 pence, but already on the 10th of January 1840 it was further reduced to 1 penny. At the same time, the number of letters sent increased from 76 million annually before 1839 to 169 million in 1840, and to 347 million in 1850. In 1840, half of the letters were in an envelope. In 1850, 5 out of 6 letters were in an envelope. This means that by 1850 the consumption of envelopes in Great Britain had reached over 300 million envelopes annually. Great Britain and its associated colonies were a special case. The rest of the world was not sending mail or using envelopes at the same rate. As late as 1890, the annual consumption of envelopes in the US had not yet passed 25 million. I have not found figures for the annual use of envelopes in Norway in 1862, the year Andrine’s letter is sent, but most Norwegian letters I have seen from before 1865 do not have an envelope.

To draw a possible timeline for the development of the modern envelope, it is perhaps reasonable to start between 1750 and 1756. In 1756 Francois Boucher paints a portrait of Madame de Pompadour. She was a famous letter writer. She was the official mistress (maîtresse) of Louis XV from 1745. In the painting above we can see something resembling an envelope lying on the table next to her. Also Boucher painted another painting for Madame de Pompadour in 1750. It is called The Love Letter. Also in this painting we can see what seems to be an envelope on the lap of one of the women. These two paintings contain some of the earliest known images of something that looks like modern envelopes. Some might argue that these are just letters that have been folded this way. Before the envelope, it was common to write on one side of a sheet of paper and then fold the sheet in different ways to hide the contents. I doubt this can explain the envelopes in these paintings. Not least because folding a normal sheet of paper will not produce the results we see in the pictures. Also, it is claimed that it was already common at the French court at that time to send notes to each other in hand-made envelopes.

I have found very few references to old envelopes. In Notes and Queries (1868, pp. 56-57) it is claimed that Mr. Clarence Hopper found an envelope resembling a modern one. It was dated the 16th of May 1696. It was sent from Sir James Ogilvie and addressed to the Right Hon. Sir Wm. Trumbull, Secretary of state. It is also claimed that envelopes were used in China as early as 200 BC., but they had a different function. They were largely intended for sending monetary gifts to one another.

In 1838, paper manufacturer John Dickinson shows a newly developed envelope where four corners meet at a point that can be sealed. The e-mail icon used today seems to be a clear relative of both this envelope and the one lying on the table next to Madame de Pompadour. The American Maynard H. Benjamin, claimed that the envelope function, i.e. covering, storing, sealing or hiding a message to be sent, has a history that can be traced back at least to the Babylonians 2000 years BC. Probably also somewhat earlier. The Babylonians wrote documents and messages by inscribing characters on clay tablets. The clay tablets were then burned to make them durable. The incriptions were sealed with fresh clay for the journey. The recipient removed the outer unburnt clay to read the message. However, I believe that Madame de Pompadour’s envelope from 1756, and the envelope in the painting The Love Letter from 1750, can serve as reasonable starting points for the modern envelope as we know it today.

The first partially machine-produced envelope can be traced to a patent issued on the 21st of January 1840. The machine is referred to as “an improved paper-cutting machine”. It was introduced by Mr. George Wilson of London. I suspect the envelope pictured above may have been cut with Wilson’s machine. The envelope is from 1841. It is only the second year that it is possible to send letters using a stamp. The Practical Mechanics Journal of 1850 states that many envelope makers were still using Wilson’s machine in 1850. The earlier alternative was to use a thin die. It often gave the envelopes an inaccurate shape. Wilson’s machine still required the envelopes to be folded by hand.

In 1845, Edwin Hill and Warren de la Rue make a new technological step by taking out a patent for an envelope folding machine. Some believe that Edwin Hill shows the predecessor of this machine as early as 1840. Only later does Warren de la Rue buy into the project and then participates in improving it towards a patent. However, the Edwin and Warren envelope machine was first shown publicly in 1851. Warren de la Rue was the son of Thomas de la Rue. The machine was put into use in this large company that exists to this day. Among other things, they are known for having produced the first machine-made playing cards (1831), for the production of banknotes and not least for the production of very good fountain pens. Edwin and Warren’s machine could fold 42 envelopes per minute and had a daily output (10 hours) of 25,200 envelopes. It was a big improvement from manual folding. With an apprenticeship of 6-8 months, a young girl could manage to fold 2,500-3,500 envelopes a day.

In 1855, the firm West and Berlin in New York were among the biggest envelope manufacturers in the United States. The envelopes were still folded by hand. They employed 100 people and managed to produce 200,000-250,000 envelopes a day. It wasn’t until 1856 that they started using their first envelope folding machine. The company still exists. Today it is called Berlin & Jones Co Inc. They are considered to be America’s first envelope manufacturer and are, together with the firm of Thomas de la Rue & Co (De La Rue), among the oldest manufacturers still in existence.

Andrine’s envelope is from 1862. It is probably machine cut and also appears to be machine folded. If the latter is the case, it is part of a technology that is at most 11 years old at the time. If the envelope is machine folded in the USA, it is a maximum of 6 years. If you study letters from the same period in Norway, you will see that they are most often in the form of folded letters. This is a letter without an envelope where the sheet the letter consists of both functions as the paper you write on and becomes its own “envelope” when folded. Andrine’s envelope is so unique that on the 2nd of November 2021 Store Norske Leksikon (The Great Norwegian Encyclopedia) updated the information they had about envelopes. Previously, it stated that the envelope was invented in 1878. On the 8th of November 2021, constructive adjustments were also made to the word “konvolutt” (envelope in Norwegian) on the pages of the Norwegian Wikipedia . We are happy to be able to contribute. It’s good that someone preserved Andrine’s envelope all these years.

Sources:

Maynard H. Benjamin (2003). The History of Envelopes – 1840-1900. Envelope Manufacturers Association and EMA Foundation for Paper-Based Communications 2002

The Royal Commission (1851). Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. Official Descriptive and Illustrated Catalogue. London: William Clowes and Sons (pp.542-543)

Practical Mechanic’s Journal and Patent Office (1850). The Practical Mechanics Journal, Volume 2 – April 1849-March 1850. Glasgow, London and New York (p.169-170)

Alexander Machintosh (1846). A General Index to the Repertory of Patent Inventions, and other Discoveries and Improvements in Arts, Manufactures, and Agriculture from 1815 to 1845, Inclusive . London: Machintosh Printer

The Metropolitan Magazine (1840) – Vol XXVII January to April 1840. London: Saunders and Otley. New Patents (p. 93)

EMA – Envelope Manufacturers Association (2020). The Ema Guide to Envelopes and Envelopes and Mailing. Alexandria: Virginia (pp. 4-8) Notes and Queries: A Medium of Inter-Communication for Literary Men, General Readers etc. Fourth Series – Volume Second. July-December 1868. London: Published at the Office, 43 Wellington Street, Strand, WC (pp. 56-57) Andrew Pritchard (1847). English Patents; Being a Register of all those Granted for Inventions in the Arts, Manufactures, Chemistry, Agriculture, ETC., ETC., During the First Forty-Five Years of the Present Century. London Wittaker and Co (Inventions 1840, p.387, no.5853)