Point to Paper – The Norwegian hatter that got in trouble with the Sheriff

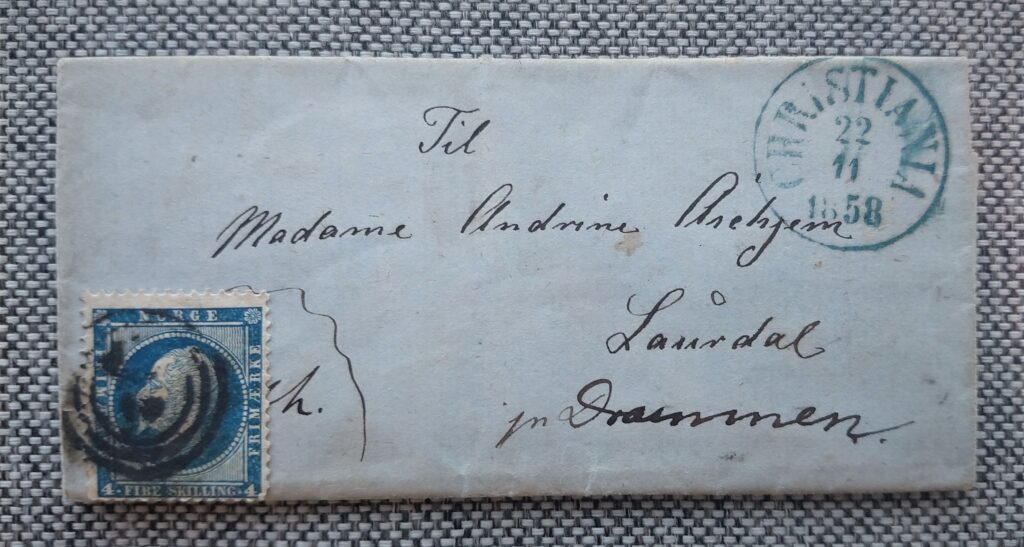

In a previous post, I wrote about the special envelope Andrine Aschjem received from her husband Hans Jakob just before Christmas in 1862. Hans Jakob Aschjem was a member of the Norwegian Parliament for Jarlsberg and Larvik County. His wife Andrine lived during this period at home on their farm Grini. It still exists and is today located in Larvik municipality. Four years earlier, in 1858, Andrine received another letter. It was written by her friend Lise Kahrs. Lise lived in the capital Kristiania (Christiania). This letter is the starting point for the story I am going to tell today. The letter has taken me on a journey I had not imagined beforehand. Now I want to share it with you.

Today I promise a slightly chaotic tale. I will drown you in perspectives and details. There will be a bit about mercury, rebellion and syphilis. There should be something for everyone. There is even a thread running through it all though it is sometimes razor thin and faintly pink. I apologize if readers find it difficult to follow.

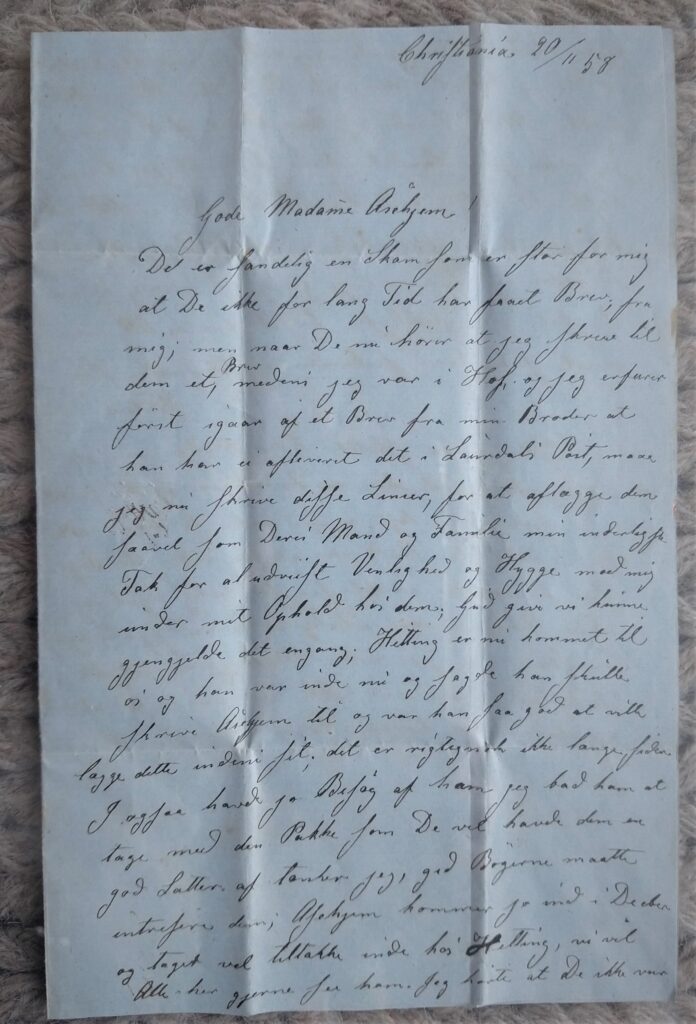

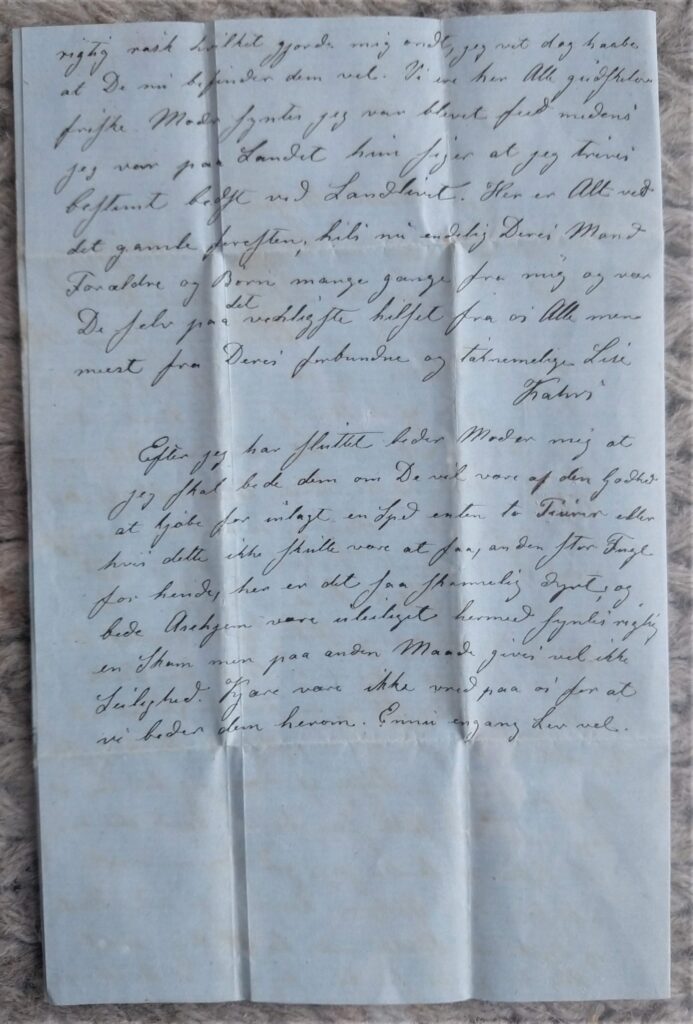

You will also see an example of beautiful personal handwriting. The penmanship belongs to Lise Kahrs. It is neat, elegant and easy to read. If you want to try to imitate it, you need a dip pen with an extra fine and flexible pen nib. They are still easy to get hold of ( e.g. here ). Be aware that they require a light hand, a well thought through writing style and some practice. Most people can learn to write like this with a few minutes of daily practice for three to four weeks. My own great-grandmother could write like this from age 10. She was not a special case. It was simply expected at that time. Here is an example of a training plan that I have used myself: The Palmer Method of Business Writing.

The events in today’s story take place between 1851 and 1858. It is a period of important social struggles and major changes. There is a national fight for the right to vote for ordinary people (men) and for the rights of working people. As always, daily life carries on in the background. I’ve always loved that part of the story. The big stories often get all the attention at the expense of the small stories from everyday life. We celebrate the great inventions and the spectacular events. We seem to forget that it is the everyday things that make life come together. Where would we be without cookware, footwear, soap, a roof over our heads and our daily bread? Where would we be without family, friends, weddings and funerals?

Today you will get to know some big-mouthed and quarrelsome men who fight for principles, rights, law and power. The things included in the more violent part of the narrative are everything from ropes and pitchforks to waterfalls and cannons. You will also get to know a mild lady. She writes a letter on an ordinary day. She is concerned with nurturing the relationship with her friend. The things she uses are everyday items from this period. She writes with a pen dipped in ink and on paper. She arranges for the letter to be shipped with the help of a stamp, an address and a preferred transit (via Drammen).

We’ll take the violent narrative first. It started in a town in Ringerike on the 22nd of July 1851. That was the day the hatter Halsten Knudsen was to be questioned by the town sheriff of Hønefoss. Knudsen was an immigrant, but most people in Hønefoss knew him. He had lived in town since 1835. As a young man, he was lucky and got a job as a journeyman with the local hatter. His name was Andersen. When Andersen died, Knudsen married the widow and took over the business.

Unfortunately, Knudsen took over the company at the wrong time. For many years it had been possible to make a living as a hatter. Knudsen’s parents had probably nodded in recognition the day he came home and told them what he wanted to become. The future is, as always, difficult to predict. Suddenly something happens that changes the everyday life of many people who work with the same thing. Inventions such as the typewriter brought an abrupt end to anyone writing documents by hand. Sewer pipes and water closets made the businesses of the night soil men redundant. Once upon a time, sitting at a counter in a bank was a common profession. Today it has become a rare job in Norway. Most customers have become their own bank employees at home at the kitchen table or in the corner of the sofa with their smartphone om their lap. The hatmaking industry was in 1851 affected by the change in fashion. It was no longer fashionable to wear a hat. Now suddenly everyone wanted a knitted beanie. It may be this unfortunate event changed the fate of Halsten Knudsen.

Without claiming that the following also applied to Knudsen, it was not unknown at the time that hatters could be quarrelsome and big-mouthed. Many hatters were actually mentally unbalanced. Madness and hat making often went hand-in-hand. The Mad Hatter from “Alice in Wonderland” was precisely inspired by the sad fate of many hatters. How the madness became a regular part of the hatter’s profession is a strange story. I think I have to tell that part of the story too.

It all started with urine and camels. It was a tradition in Turkey to add camel urine when making hat felt from camel hair. The urine caused the scales on the camel’s hair to open and helped the felting process. French hatters found camel urine difficult to obtain and therefore began to use their own. At one specific hatter’s workshop, something strange happened. One of the hatters consistently made finer hat felt than all the others. He didn’t really do anything different than the rest. The only thing they could figure out was that there must have been something unique about his urine.

They were absolutely right. This hatter had syphilis. It wasn’t really the venereal disease that contributed to him getting the finest hat felt, but it was the way the disease was treated that made the difference. He was treated with mercury. Mercury was the medicine offered to those affected by syphilis. The mercury ended up in the urine and helped make it extra suitable for making good hat felt.

Mercury eventually became a common ingredient in the production of finer hat felt. The liquid and toxic metal made it possible to make felt of a quality that had never been seen before. The new discovery, however, was not so good for the hatters themselves. Just imagine when the hats had to be steamed into shape and the mercury vapor had free access to the bloodstream through the lungs. Mercury poisoning could make the hatters both short-tempered and mentally highly flammable. It is in many ways a tragic story about poor working conditions. Many different industries knew early on about the harmful effects of being exposed to mercury vapor. In the US, however, mercury in hat production was not banned before 1941. Hundreds of tonnes of mercury are still being used annually in the world. Much is used in connection with questionable small-scale production of precious metals such as silver and gold. The use of mercury is not declining despite the very high cost for the invironment.

Knudsen was part of the early labor movement. That was not madness. There were many important issues to fight for. There were also many good people who participated. Marcus Thrane, a famous and important Norwegian politician and activist, was one of them. Unfortunately, the feud in Hønefoss did not end well. It would be many years before the labor movement regained the courage and strength to fight on.

Halsten Knudsen was arrested for rebellion. On the way to the local jail cell, his comrade Helge Gunbjørnsen Tyodden shouted to the spectators: “It must be a bad idea to let the authorities take Knudsen!”. It turned into a riot. A group of fifty men freed Knudsen. Comrade Tyodden took part in getting the sheriff hanged by his feet from the main bridge in the town. They threatened to cut the rope and release the sheriff into Hønefossen (translation: “the chicken falls”). Knudsen escaped from the city, but did not feel finished with the matter. He eventually mobilized over 300 men. For a while it looked like there might be war in the city. The rebels marched towards Hønefoss. They lost heart when they heard that two companies from the Norwegian Hunter Corps and a company from Modum were ready to meet them. The thought of facing two 6-pounder guns and three companies of trained soldiers armed with rifles was just too much. The hatter’s gang was mostly equipped with agricultural implements. The famous Norwegian author Henrik Ibsen wrote about “Hattemagerfeiden paa Ringerike” (“The Hatters Feud at Ringerike” – Hønefoss is the main town in Ringerike) in the magazine Andhrimmer in 1851.

Knudsen was finally arrested again and died in prison of cholera on the 3rd of July 1855. He was buried in the cholera cemetery at Tøyen in Oslo. The sheriff who dangled from his feet over Hønefossen was called Lars Andreas Robsahm. He was sheriff in Ringerike for more than 50 years.

The sheriff contributes to the thin pink thread connecting the softer everyday narrative. The future daughter-in-law of Sheriff Robsahm was called Elise Marie Kahrs (1824-1907). She married the sheriff’s son Edvard Johan Robsahm in 1866. They married just over a year after the sheriff died. The letter you are about to get to know was written in 1858. That is eight years before she married Edvard and seven years after the feud at Hønefoss. At the time she wrote the letter, it seems that she lived in Kristiania with her mother. She was 34 years old and unmarried. When she married Edvard in 1866, she was 42 and he was 49. They have no descendants.

Elise Marie Kahrs signed her letters with Lise Kahrs. The letter she sent to Andrine Aschjem was a so-called entire letter. That is to say, the letter itself was folded in such a way that it also became the letter’s envelope. The whole letter only consists of a single sheet of paper the size of a standard A4 sheet. The letter, fully folded to look like an envelope, measures just 5x11cm (53x107mm). Lise Kahrs wrote the whole letter on two halves of the A4 sheet. This means that the letter fits on one side of an A4 sheet. The writing is small, lovely, easy to read and accurate. She probably wrote with a flexible metal nib (gold or steel). By today’s pen standards, the nib was probably XF (extra fine). There is clear variation in the line width in the writing. This means that the down-stroke of the line is slightly thicker than the up-stroke. This is possible because the pen nib is thin enough and flexible enough to give variation in the writing. A nib like this allows a slightly heavier down-stroke than up-stroke. This heavier down-stroke often occurs naturally when writing with a very flexible nib. The nib will give resistance and might even be damaged if you are not very light on your up-stroke.

Lise Kahrs writes:

Christiania 20/11 58

Dear Madame Aschjem,

It is indeed a great shame for me that you have not received a letter from me for a long time, but when you now hear that I wrote you a letter while I was in Hof and I only learned yesterday of a letter from my Brother, that he didn’t deliver it to Laurdal’s Post Office, I must now write these lines, to give you as well as your husband and family my most heartfelt thanks for all the kindness shown and having fun with me during my stay with you, God grant we could reciprocate once; Hetting has now come to us and he was inside now and said he was going to write to Aschjem and was he so good as to put this inside his; it is true that it was not long ago that you also visited the sea, I asked him to take the package with to you, which you must have had a good laugh of thoughts, given that the books might interest you; Aschjem is coming here in December and will probably be paying his respects to the Hetting’s, we would all like to see him here. I heard you weren’t

really well, which hurt me, but I would like to hope that you are now better. We are here, thank God, everyone is healthy. Mother thought I had gotten fat while I was in the country, she says that I definitely enjoy country life best. Here it is all like always, by the way, now at last greet your husband, parents and children many times from me and yourself the most heartfelt greetings from all of us, but mostly from your loyal and grateful Lise Kahrs,

After I finished writing, Mother asks me to ask you if you would be so kind as to buy for a special price either two capercallies (wood grouse) or, if this should not be obtainable, another large bird for her, here it is so shamefully expensive; and asking Aschjem to be inconvenienced by this seemed like a real shame, but in another way no accommodation is given. Beloved, don’t be angry with us for asking them this. Once again Live well

All the pictures are taken by Kjartan Skogly Kversøy. The illustrations are drawn with dip pen and iron gall ink and are also done by the same Kversøy.

2 thoughts on “Point to Paper – The Norwegian hatter that got in trouble with the Sheriff”

Love it!